Mongolian Microfossils Could Be Earth's First Animals

Transitional moments are often hard to pinpoint in evolutionary history. Because changes to species can occur gradually over long periods of time, it is difficult to know exactly when birds diverged from non-avian dinosaurs or when humans branched off from their primate ancestors.

The mother of all such moments — when microbes evolved into animals — is even more challenging to identify given the long-ago age of that landmark event.

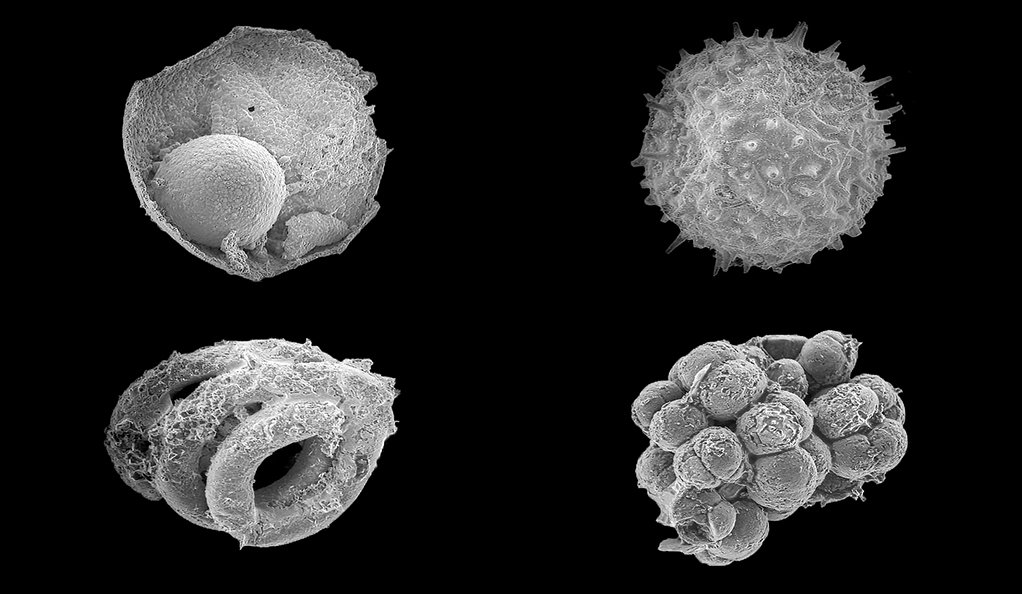

A newly found assemblage of microfossils dating to 540 million years ago could help to solve the mystery. The authors of the discovery, writing in the journal Geology, believe it is possible that many of the fossils belong to the putative animal Megasphaera.

"If the fossils do represent an animal, it would be the oldest animal in the fossil record," lead author Ross Anderson of Yale University and the University of Oxford told Seeker.

He added, however, that "interpretations of the group of organisms which the fossil represents have proved controversial over the last 20 years."

Some researchers have concluded that similar fossils are of sulphur-oxidising bacteria. Still others think they are the remains of green algae.

Shuhai Xiao of Harvard University and colleagues, writing in the journal Nature in 1998, were among the first to propose that such fossils are the remains of multicellular animal embryos. Since then, numerous "embryo-like" fossils have been unearthed at the 600-million-year-old Doushantuo Formation of South China.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Mongolian fossils, discovered at that country's Khesen Formation to the west of Lake Khuvsgul, are younger. Anderson and his team dated them to 540 million years ago.

The scientists decided to excavate the site in northern Mongolia because it consists of numerous phosphorites, which are sedimentary rocks that contain a high proportion of calcium phosphate. The rocks at Doushantuo are of a very similar composition.

"In terms of the fossils present (at Khesen) there are a lot of similarities" with those at Doushantuo, Anderson said. "The fossils are also preserved in the same manner as those found in the Doushantuo Formation, yielding the exceptional cellular level of preservation."

He and his colleagues suspect that many of the microfossils preserve different stages of embryonic development whereby cells divide and multiply.

"For example," he said, "we have specimens with only a single internal cell, but others with up to 100."

As for how single-celled organisms evolved into multicellular ones, there are many possibilities.

Anderson explained that an increase in the availability of oxygen; genomic evolution, which may provide new biological equipment; changes in nutrient cycling; continental reconfiguration, which opens up new habitats; and greater predation could have been factors.

He added that evaluating these hypotheses requires a good temporally calibrated fossil record to test correlations to environmental change. Since the Mongolian microfossil assemblage extends both the location and timing of Megasphaera, it moves the researchers one step closer to that goal.

The new study is just "the tip of the iceberg," Anderson said.

"This summer, we carried out new fieldwork in Mongolia and collected many more samples from which we can extract fossils," he continued. "We are also working to unravel the environmental history of the region so that we can place the fossils in an environmental context and understand their ecology."

If he and his colleagues can unequivocally prove that Megasphaera was indeed an animal, the tiny creature would hold a significant position at the base of the entire animal kingdom's tree of life.

Originally published on Seeker.