Here's How Space Travel Changes the Brain

Spending prolonged time in space can lead to striking changes in an astronaut's brain structure, a new study finds. These changes may help explain some of the unusual symptoms that astronauts can experience when returning to Earth.

In the study, researchers scanned the brains of 34 astronauts before and after they spent time in space. Eighteen of the astronauts participated in long-duration missions (close to six months, on average) aboard the International Space Station, and 16 astronauts participated in short-duration missions (about two weeks, on average) in space shuttle flights.

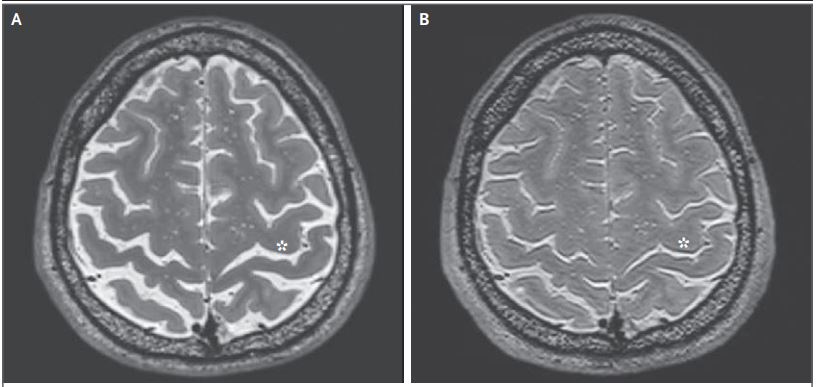

The brain scans revealed that most astronauts who participated in long-duration missions had several key changes to their brain's structure after returning from space: Their brains shifted upward in their skulls, and there was a narrowing of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) spaces at the top of the brain. (CSF is a clear liquid that flows between the brain and its outer covering, and between the spinal cord and its outer covering.) However, none of the astronauts on short-duration missions exhibited these brain changes.

In addition, the scans showed that 94 percent of the astronauts on long-duration missions had a narrowing of their brain's central sulcus, a groove near the top of the brain that separates the frontal and parietal lobes (two of the four major lobes of the brain). Only 19 percent of astronauts who participated in short-duration flights showed a narrowing of their central sulcus. [7 Everyday Things That Happen Strangely in Space]

Although researchers have known for years that the microgravity conditions in space affect the human body, the new study is one of the most comprehensive assessments of the effect of prolonged space travel on the brain, said study co-author Dr. Michael Antonucci, a neuroradiologist at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC).

"The changes we have seen may explain unusual symptoms experienced by returning space station astronauts and help identify key issues in the planning of longer-duration space exploration, including missions to Mars," Antonucci said in a statement.

In particular, the findings may help researchers better understand a condition seen in some astronauts known as "visual impairment intracranial pressure syndrome," or VIIP syndrome. Astronauts with this condition have poorer vision after their space travel, along with swelling of the eye's optic disk and an increase in pressure inside the skull.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's not clear exactly what causes VIIP syndrome. In the new study, three astronauts had symptoms of VIIP syndrome when they returned to Earth, and of these, all three experienced a narrowing of the central sulcus. One of these astronauts also had imaging available to show that there was an upward shift in the position of the brain.

The researchers hypothesized that an upward brain shift, along with "crowding" of tissue at the top of the brain, may lead to obstruction of CSF flow, subsequently increasing pressure in the skull and resulting in optic-nerve swelling. But more studies that use more detailed brain imaging will be needed in order to prove this hypothesis, the researchers said.

In addition, more studies are needed to assess astronauts' brains for longer periods after they return to Earth, said Dr. Donna Roberts, an associate professor of radiology at MUSC who led the study. This will help researchers determine if the brain changes seen in their study are permanent, or if they reverse at some point. (The participants in the current study had their brains scanned about four to 10 days after they returned to Earth.)

Ultimately, the researchers hope their studies will help them better understand the effects of long-term space travel on the brain, and find ways to make space travel safer.

"Exposure to the space environment has permanent effects on humans that we simply do not understand," Roberts said. "What astronauts experience in space must be mitigated to produce safer space travel."

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.