Secret Chamber? Cosmic Rays Reveal Possible Void Inside Great Pyramid

A large void has been discovered inside the Great Pyramid of Giza, thanks to cosmic rays. If the large space turns out to exist, its function — which could be anything from new chamber to sealed-off construction passage — is likely to be the source of much archaeological debate.

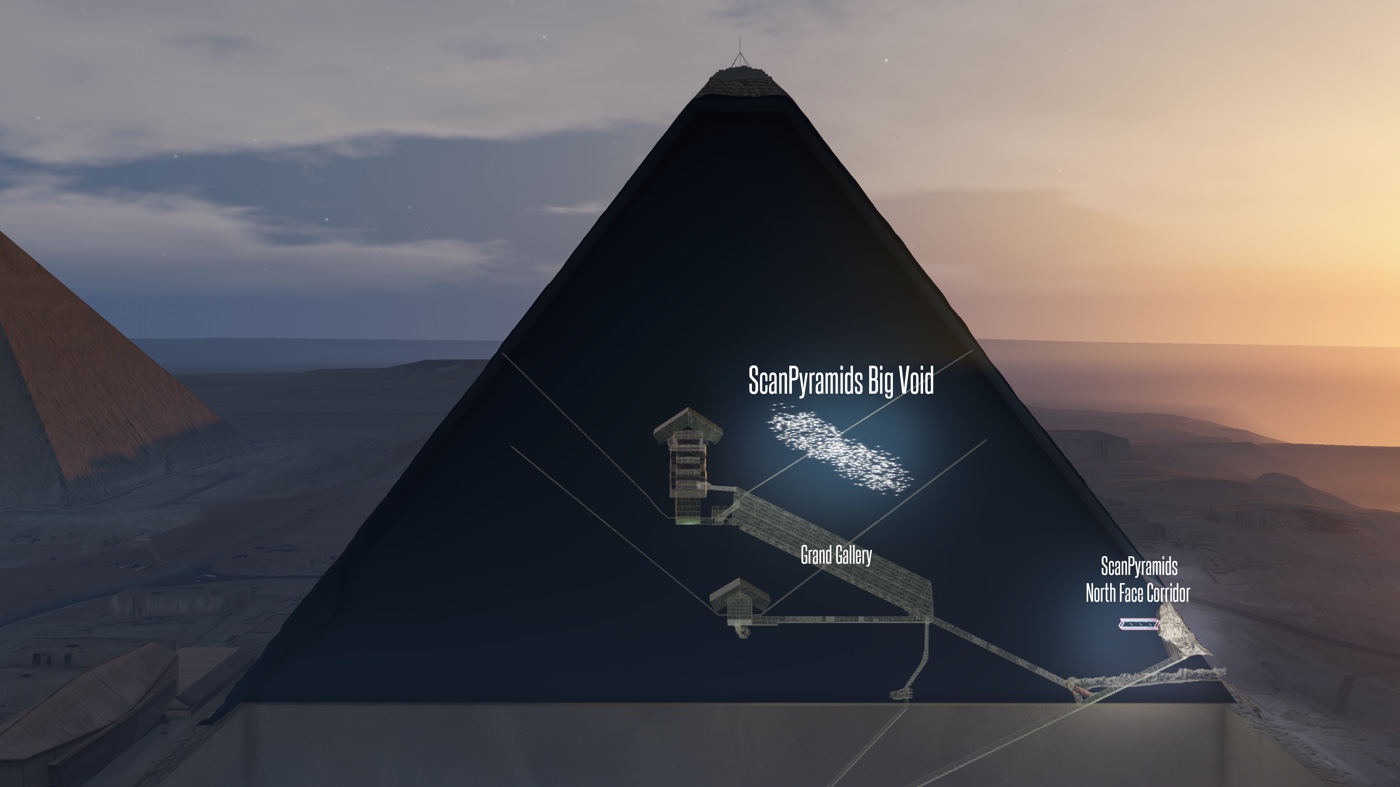

An international group of researchers reported today (Nov. 2) in the journal Nature that by tracking the movements of particles called muons, they have found an empty space more than 98 feet (30 meters) long that sits right above the granite-walled Grand Gallery within the massive pyramid. The Great Pyramid, also known as Khufu's pyramid, was built during that pharaoh's reign between 2509 B.C. and 2483 B.C. No new rooms or passages have been confirmed inside the pyramid since the 1800s.

"The void is there," said Mehdi Tayoubi, the president of the organization Heritage Innovation Preservation and a leader of the ScanPyramids mission, an ongoing effort to bring new technology to bear on Egypt's most famous structures. [In Photos: Looking Inside the Great Pyramid of Giza]

However, the announcement met some skepticism within the Egyptology community.

"It's very clear what they found as a void doesn't mean anything at all. There are many voids in the pyramid because of construction reasons," said Zahi Hawass, an Egyptologist and former Egyptian minister of antiquities and director of excavations at Giza, Saqqara, Bahariya Oasis and the Valley of the Kings.

Blank spaces

Tayoubi and his colleagues have a somewhat unusual approach to the pyramids. They deliberately avoid involving Egyptologists in the scanning stages of their project, preferring to come to the pyramids with a "fresh, and maybe a naïve eye," Tayoubi told reporters. The idea, he said, is to avoid preconceived notions on what should be present in favor of cold, hard physics data.

The team discovered the mystery void using muon particles, which form when cosmic rays interact with Earth's upper atmosphere. A shower of these particles falls on the planet constantly, zinging through ordinary matter at close to the speed of light. Muons can penetrate stone, but as they travel through a dense object, they lose energy and eventually decay. Thus, measuring the number of muons flowing through an object from a particular direction can reveal the density of that object. If there's a void inside the object, more muons than expected will penetrate. [Photos: Amazing Discoveries at Egypt's Giza Pyramids]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers used three different detection methods to measure muons in and around the Great Pyramid. They started with nuclear emulsion films developed by researchers from Nagoya University in Japan, which are like ordinary camera films except they capture the movement of not just visible light, but highly energetic particles.

A second method, using particle detectors called hodoscopes, was developed by researchers from KEK, a high-energy accelerator research organization in Japan. Both of these detectors were placed in areas inside the pyramid. A third method, which uses argon-gas-based detection of muons, was installed by scientists from the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) outside the pyramid walls.

Each method of muon detection has pros and cons, Tayoubi said. Emulsion films are very precise, but last for only about 80 days of measurement, for example. The two electronic devices offer measurements that are not as precise but can run for longer periods of time, gathering greater amounts of data.

Construction controversy

All three detection methods returned the same result: There is an empty space where none was expected to be. The Great Pyramid has three known chambers: A subterranean chamber, a Queen's Chamber, and higher up, a larger King's Chamber. These are connected by several corridors, including the massive Grand Gallery, an empty hallway 28 feet (8.6 m) tall, 153 feet (46.7 m) long and just over 3 feet (1 m) wide.

The newly detected void seems to sit right above the Grand Gallery, though the research team can't yet pinpoint its precise orientation or shape.

"We should be very cautious at this time in going too far beyond the observation of the void, because this void needs more research of its orientation and dimension in order to be able to conclude something more precise," said Hany Helal of the University of Cairo, the coordinator of the ScanPyramids project.

In 2016, the same researchers reported that they'd found void space behind the north face of the pyramid.

Reactions to the new announcement within the Egyptology community were mixed.

"The void can be another chamber or a gallery, an aerial shaft, or an architectural fault that was sealed off," said Monica Hanna, an archaeologist, Egyptologist and founder of Egypt's Heritage Task Force, which focuses on protecting ancient sites. Hanna said nondestructive methods of studying the pyramids were a valuable way to investigate the original design of the pyramid without having to destroy parts of the structure.

Hawass was more dismissive.

"We have to always be very careful about the word void, because the Great Pyramid is filled with voids," he said. The builders of the pyramid set stones of varying size and shape in its core, Hawass said, so the whole structure is riddled with gaps. The original designers of the pyramid also left sealed-off construction tunnels. Identifying these voids has more to do with publicity than with advancing knowledge of the pyramid, Hawass said.

"It has nothing to do with any secret rooms or anything inside the Great Pyramid," Hawass said. He said he and his colleagues on the committee that reviews findings from Giza plan to author a paper explaining what they prefer to call "anomalies" from an Egyptology standpoint.

Tayoubi and his colleagues, however, argue that the void is not the result of uneven construction, because even blocks of varying size and orientation would have absorbed the muons they observed.

"From an engineering point of view and from a structural point of view of analysis it cannot be an irregularity," Helal said.

However, there are no plans at this point to investigate the void in person. There is no way to access the void through existing corridors or chambers, and Egyptologists no longer approve of destructive methods of studying pyramids and other ancient structures.

It may be possible to put additional muon detectors inside the King's chamber for a view of the void from new angles, Tayoubi said.

"We want more data in the Great Pyramid," he said. "The question is a question of means and partners and how we can continue."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.