In Photos: Cave Art from Mona Island

Subterranean cave art

Archaeologists recently explored the many subterranean caves of Mona Island. Exploring deeper in the narrow tunnels than ever before, the researchers uncovered thousands of well-preserved paintings and dated them to before Europeans arrived on the island — third-largest island in the Puerto Rican archipelago.

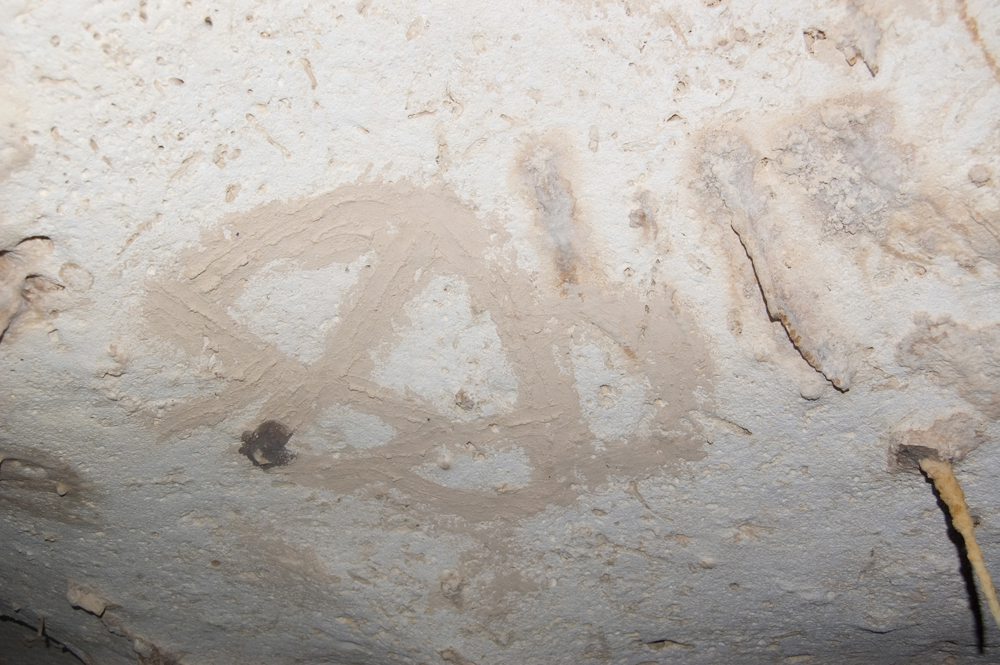

Artistic rubbings

Some of the artwork was rubbed into the walls and some was painted with mixtures of local plant materials, minerals and charcoal, according to the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Spiritual shapes

The caves were a spiritual place to the Taíno people, who were indigenous to Mona Island, and many of the rubbings, like this one, likely depict local ceremonies, the researchers said.

Dating art

While some of the artwork had been discovered in the past, no one had analyzed it with carbon dating.

Cave art age

The scientists used X-rays and carbon dating to determine that the artwork is 500 years old.

Human-like figures

By rubbing away the softer, outer layer of the rock walls, the Taíno people often depicted human-like figures with faces and arms.

Rainy deity

In the Taíno religion, Boinayel, depicted here, was a deity responsible for rain and flooding, who constantly fell in and out of balance with his sun-deity brother, Marohu.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Boinayel

Here, one of the scientists checks to see just how old that depiction of Boinayel is.

Covered in art

Over the centuries, thousands of rubbings and paintings eventually coated the walls and ceilings of Mona Island's caves.

Charcoal speleothems

Researchers discovered that charcoal speleothems, or mineral deposits formed from the limestone cave's chemical interactions with groundwater, had formed throughout the tunnels.

Making art

By using carbon dating techniques on the calcite secretions that covered some of the artwork, the researchers concluded that the Taíno people must have returned throughout the 13th to 15th centuries to add more art to the caves.