Under Her Spell: A 'Witch' Shows Her Face, 300 Years After Her Death

Lilias Adie was an elderly woman who lived in the village of Torryburn, Scotland. According to local legends, in 1704, a neighbor accused her of plotting evil mischief. During Adie's interrogation, she confessed to trafficking with the devil, and died in prison shortly after her confession, before she could be burned alive for her alleged crimes.

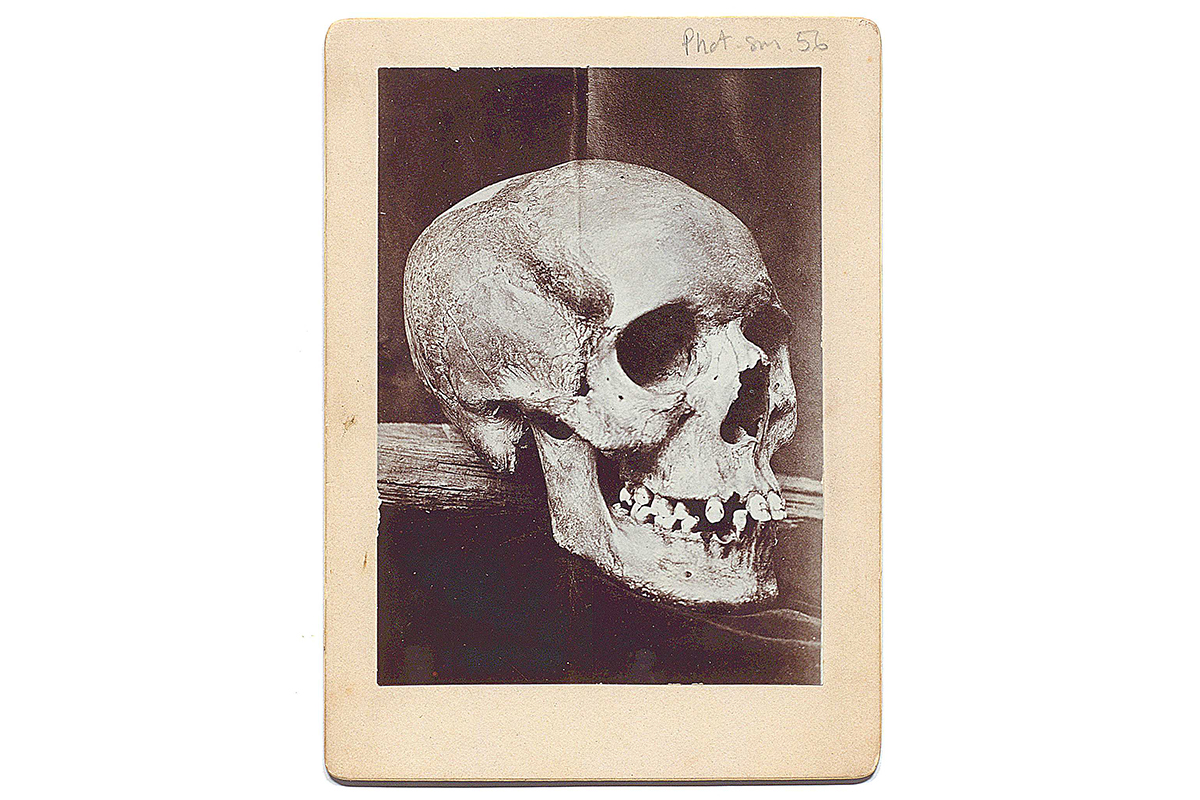

Recently, researchers with Scotland's Centre of Anatomy and Human Identification at Dundee University (CAHID) digitally modeled Adie's face. They worked from photographs of her skull, which was formerly in the collection of the St. Andrews University Museum, but had been lost sometime during the 20th century, University of Dunee representatives said in a statement. [Black Magic: 6 Infamous Witch Trials in History]

The end result was "quite a kind face," according to forensic artist and CAHID lecturer Christopher Rynn, who performed the reconstruction of the long-deceased "witch."

"There was nothing in Lilias' story that suggested to me that nowadays she would be considered as anything other than a victim of horrible circumstances, so I saw no reason to pull the face into an unpleasant or mean expression," Rynn explained.

Between the 15th and the 18th centuries, an estimated 40,000 to 60,000 people were tried and executed as witches across Europe and in the American colonies, and up to 75 percent of the so-called "witches" were women, Live Science previously reported. Local accounts suggested that after Adie was accused, she claimed to have consorted with the devil, saying, "His skin was cold, and his colour was black and pale, he had a hat on his head, and his feet were cloven," according to the book "Witchcraft and Folk Belief in the Age of Enlightenment: Scotland 1670-1740" (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016). She also named other women who joined in midnight revels, implicating seven additional suspects.

Typically, a facial reconstruction that originates with a skull takes about 10 to 20 hours to progress from skull, to muscled face, to modeled face without the realistic skin texture, Rynn told Live Science in an email. Adie's reconstruction took nearly twice that time, as they did not have her skull in hand and had to build their digital model from photographs of it, he said.

Once forensic artists have their digital skull model, they estimate muscle size based on the skull morphology, working from anatomical guidelines in published research that define average tissue depths relative to the bone, Rynn explained. They use these guidelines as they shape muscles for the jaw, and recesses in the bone hint at the bulk of the muscle tissue, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Next, muscles of facial expression are layered on "like straps," connecting the corners of the mouth to the bone, Rynn said. Facial features are also modeled based on markers located on the skull, he added. Tooth position and protrusion determine the shape of the mouth; the structure of the eye sockets marks the shape of eye and eyebrows; and the nasal aperture is a blueprint for the shape of the nose. Skulls offer fewer clues about ears, as there is little they can reveal about the intricate whorls of ear cartilage, Rynn said.

"The rest of the facial surface (i.e. the cheeks) is estimated by fusing the muscles and skull into a single model, then growing it a few millimeters and smoothing it off to make it more of a convincing human face. Once the skin layer is there, it's a bit like meeting a person, in that the brain suddenly begins processing the image as a 'face,'" Rynn told Live Science.

In this case, Adie's reconstruction, which was conducted for a BBC Radio Scotland "Time Travels" episode that aired Oct. 31, is that of an older woman who seems much less terrifying than the purported cohort of the devil described by her accusers.

"It's sad to think her neighbors expected some terrifying monster," Louise Yeoman, a historian for "Time Travels," said in a statement.

"She was actually an innocent person who'd suffered terribly. The only thing that's monstrous here is the miscarriage of justice," Yeoman said.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.