Puppers! Our History with Canines Unfolds in 'Science Comics: Dogs'

For more than 15,000 years, people and dogs have lived and worked together. But the canines that we see today look and behave very differently from their wolf ancestors.

The story of how once-wild wolves transformed into domestic dogs — and to the hundreds of breeds currently recognized by the international organization Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI), also known as the World Canine Organization — is a tale of evolution, genetics, biology and even psychology, and is entertainingly outlined and illustrated in "Science Comics: Dogs" (First Second Books, Oct. 31, 2017) by author and artist Andy Hirsch.

"Dogs" is the latest title in a graphic nonfiction series that uses comics to explore diverse science topics: from animals and ecosystems, to technology, to the processes that power our dynamic planet. [The 10 Most Popular Dog Breeds]

In "Dogs," Hirsch uses a humorous approach — and an energetic and enthusiastic doggo narrator named Rudy — to explore the thousands of years of artificial selection and other factors that shaped Canis familiaris into a range of highly specialized body types: long-trunked and low-slung dachshunds, sleek and slender whippets, lumbering bulldogs, and all of the diverse shapes and sizes in between.

Recently, Hirsch spoke with Live Science to delve into what makes dogs uniquely suited to be our close companions, what the latest scientific research is telling us about their biology and behavior, and how the long-standing relationship between humans and dogs has changed them — and us — over time.

This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Live Science: What were the most important "big ideas" about dogs that you wanted to get across in the book?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

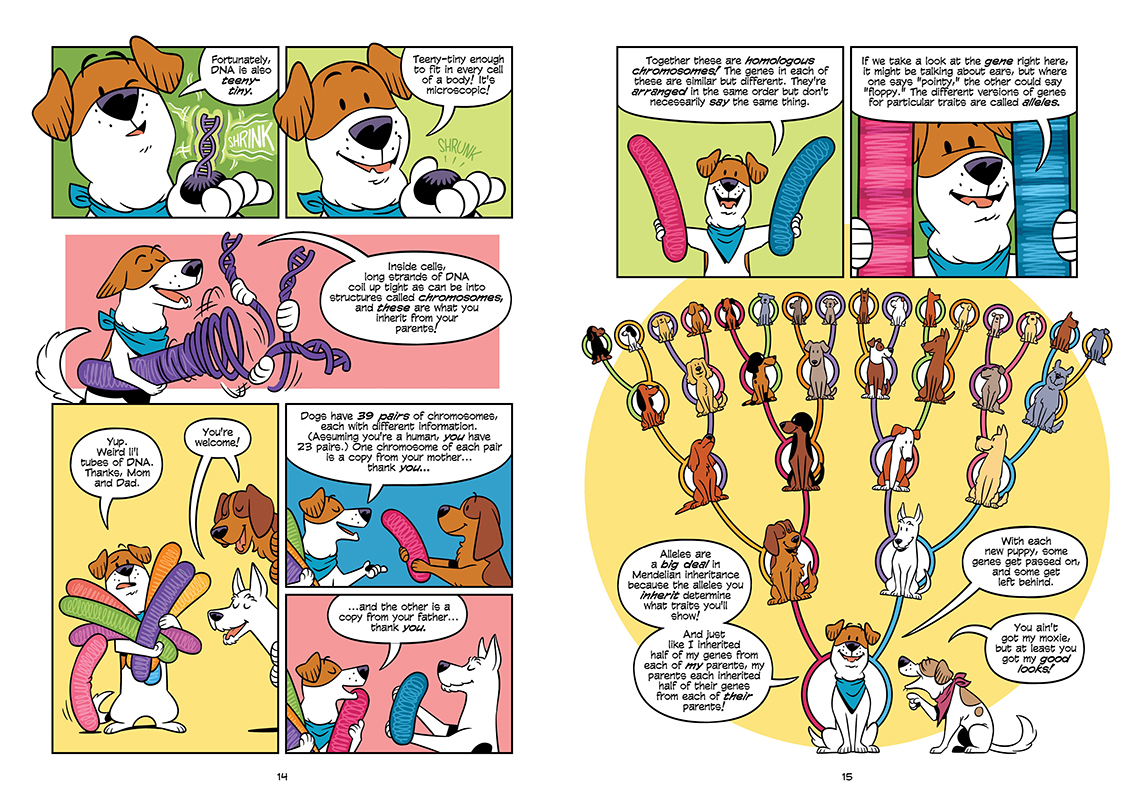

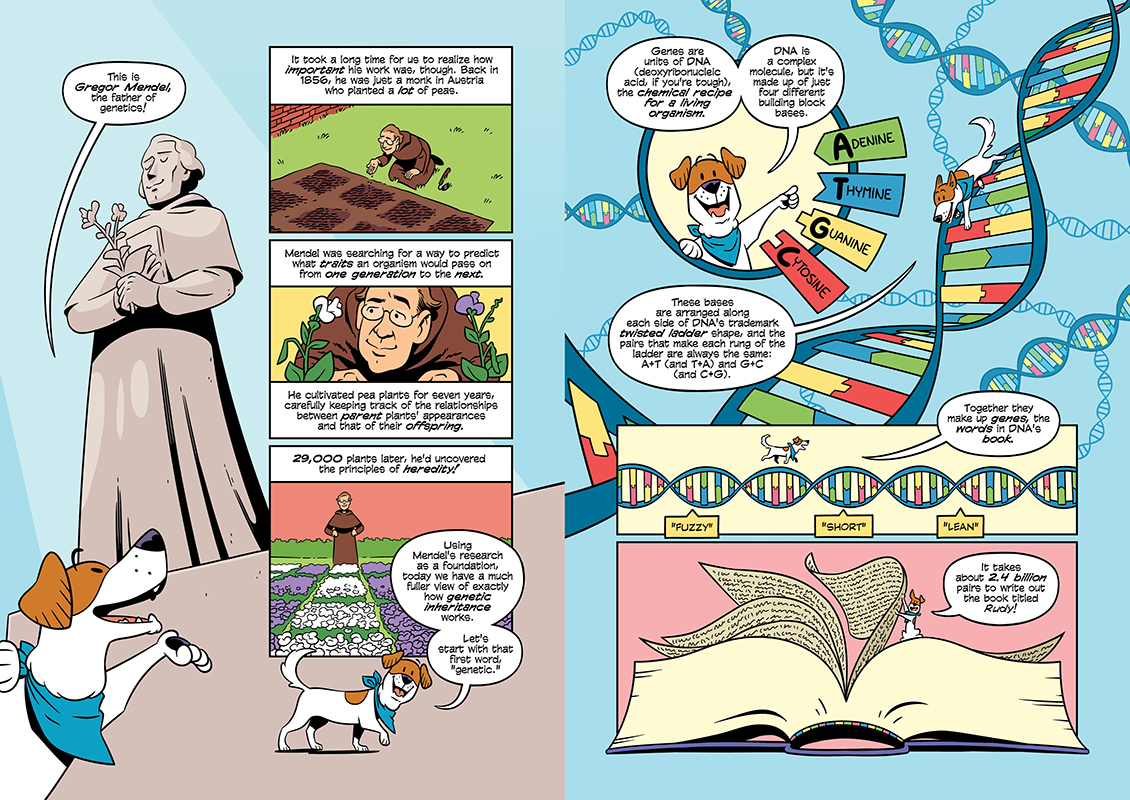

Andy Hirsch: I think it all falls under the umbrella of humans having had a profound influence on dogs. They simply wouldn't exist without us, especially any sorts of artificial breeds, so a good portion of the book is really about our methods of influence. That means lots of material about the hows: artificial (human-guided) and natural (still involving humans, actually) selection, including enough genetics to understand how one species can take so many shapes, as well as about the whys: their exceptional senses, their sociability and their capacity for cross-species communication. [Like Dog, Like Owner: What Breeds Say About Personality]

Humans and dogs have an unmatched partnership all the way at the species level, and to me that means we have a responsibility to understand and care for them. That might sound heavy, but I don't mind because dogs are just wonderful. My guiding principle was that I wanted readers to look at their dogs and think their pet is the coolest little pup in the world.

Live Science: How much did you already know about dogs when you started working on this project?

Hirsch: Less than I thought! I've kept dogs most of my life and attended basic training classes, that sort of thing, and of course I'd learned my share of biology in school. What I knew about actual canine science, however, was rooted in assumptions that were swept away as soon as I started reading the current literature.

Seriously, step one: Where did dogs come from? If you'd asked me two years ago I would have given you the old line about wolf puppies being taken in and tamed by Fred Flintstone. The real story is so much more interesting because the domestication of wolves and the origin of dogs was a natural phenomenon stemming from environmental changes. No wolves on primitive leashes, just slow, natural selection toward friendliness. Learning how wrong I'd been wasn't a bad feeling — it was a great feeling. That sense of discovery, of realizing how much more there is to this animal you accept as a family member, that's something I want to share with every page.

This is my first nonfiction book, so I also learned how to research properly in the first place. It's a serious responsibility, especially for a young audience who'll see you as an authority on the subject. I live in Texas, and the state has this really cool program that lets anyone with a public library card to access university libraries, which includes their digital subscriptions and archives. It was big help in reaching sources that would otherwise be inaccessible to the general public.

All that combined with the fact-checking expertise of actual dog scientists Julie Hecht [a canine behavioral researcher and adjunct professor at Canisius College in New York] and Mia Cobb [a zoologist with the Anthrozoology Research Group in Australia] gave the book a solid factual foundation.

Live Science: Once you had identified the general themes for the book, what helped you shape the story? At what point in the process did Rudy and his ball become a visual cue for "bouncing" from topic to topic?

Hirsch: Maybe it's something of a cheat to let a tennis ball bounce 25,000 years between panels, but that's the magic of comics!

For this particular book, narrative is secondary to effectively teaching the science. My initial outline looked more like a research paper than a goofy dog book, and I tried to organize it in such a way that the information naturally builds on itself. That often meant anticipating what questions might be raised by each topic and using those to transition into the next. This isn't a textbook, so when there's the opportunity to present some facts through an entertaining narrative aside I let the story follow it.

That's how we end up observing [zoologist] Dmitry Belyaev's silver fox experiments and Kenth Svartberg's personality gauntlet [for dogs]. The latter of those involves ghost costumes and spring-loaded dummies, and if that doesn't pique your interest, I don't know what will.

Since what I felt was the most intuitive organization wasn't strictly chronological, the tennis ball was a good way to, well, bounce from one thing to the next. Rudy is our friendly narrator, and though he's very knowledgeable, he still has the distractible nature of an average dog. That means the bouncing ball never fails to move his attention from one topic to the next. I'd like to think it's a good fit for how a curious young reader might enjoy learning — stay in one place only as long as it's interesting, absorb all you need, and move on the next cool dog topic. [The Best Science Books for All Ages]

Live Science: What aspect of dogs did you find the most interesting? Was it their genetics? The history of their relationship with people? Their senses? Or something else?

Hirsch: I think that's got to be their senses, because they shape how dogs perceive the world.

If you were able to get inside a dog's head, you'd find yourself in a very different place, and not just because you'd be several feet closer to the ground. Limited color vision makes sense for an animal used to hunting in low-light conditions. A wide hearing range makes them good guardians, the very first job humans gave them. Their sense of smell is unfathomably precise, able to detect one or two parts in a trillion, which I put some amount of time into translating to a farts-per-air-hanger measurement. Dogs' incredible noses informs everything from their long-admired skill at tracking and detection to their butt-sniffing social lives — there are information-rich pheromones back there, and lots of them. [10 Things You Didn't Know About Dogs]

Smell is worth lingering on because a primarily scent-based life is very different from the primarily vision-based one humans have. You or I might see an unremarkable patch of grass and impatiently want to get on with our walk, but there's a reason Rover — have you ever actually met a dog named Rover? I'd very much like to — is sniffing like mad. There's loads of information in that spot if you've got the nose to collect it.

Live Science: And finally — was "Rudy" inspired by a dog that you know personally?

Hirsch: Yep, the part of Rudy is played by my very own dog Brisco, whom my partner — Rudy's person in the book — and I adopted just a couple of months before I started working on the book.

"Rudy" was his first shelter name, and it's a good fit for a comic book dog. If you get a chance to draw a book full of dogs, of course you're going to make yours the star. The timing was really a case of my work and personal life running in parallel. This was the first time I'd taken in a new dog in over a decade, so I was getting to know him at the same time as I was getting to know dogs in general.

Both the book and my relationship with him are better for it, I think. We spent weeks sitting together in the living room armchair, me diligently making my way through a stack of research books to learn how dogs communicate and him curled up beside me and ready to listen. It was my favorite part of the process.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.