Antarctic Danger: Ice Shelf Cracks Close British Base … Again

Growing cracks in an Antarctic ice shelf have forced the closure of a mobile British research station for a second winter, although it was relocated earlier this year to avoid the danger of being cast adrift.

The British Antarctic Survey (BAS) announced last week that its Halley VI station on the Brunt Ice Shelf in the Weddell Sea would be closed for the forthcoming southern polar winter — from March until November 2018 — once the summer operations have ended.

It will be the second winter in a row that Halley VI has been shut for the season because of the danger that the station could be cut off by two growing cracks in the 490-foot-thick (150 meters) floating ice shelf. [Photos: Behind the Scenes of an Antarctic Research Base's Relocation]

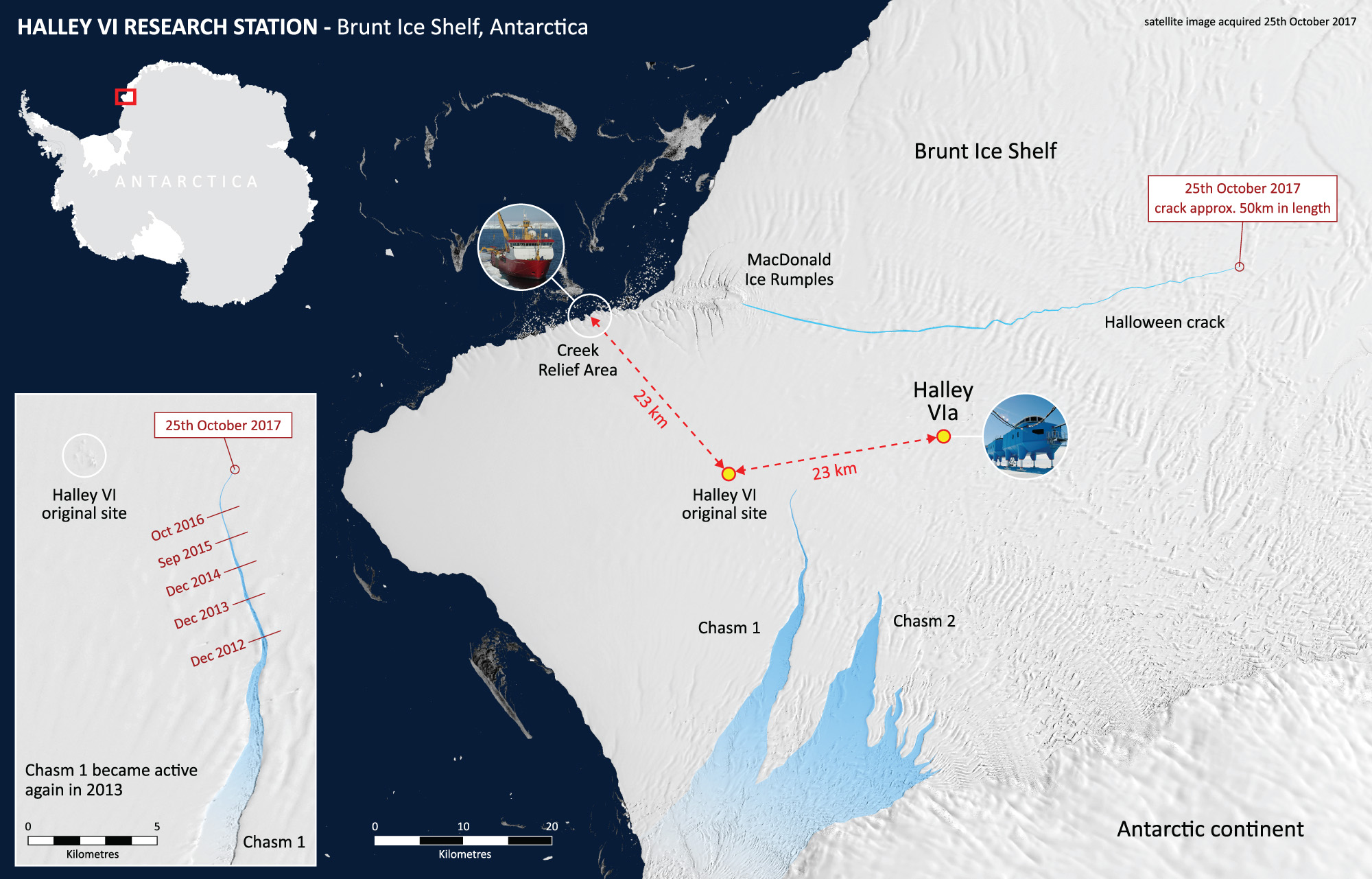

The latest assessment by glaciologists found that the expansion of a major chasm in the ice located about 12 miles (20 kilometers) from Halley VI has accelerated over the 2017 Antarctic winter, and a second crack that appeared north of the base in October 2016 – known as the "Halloween Crack" – had continued to extend eastward, according to a BAS statement.

BAS representatives said that Halley VI could be safely evacuated if either of the cracks grew enough to sever it from the main body of the ice shelf, an incident known as a "calving event," where a "calf" iceberg separates from the ice shelf.

But when faced with the possibility of having to conduct such an evacuation amid the darkness, bad weather and frozen seas of an Antarctic winter, BAS chose to close the station as a precautionary measure, BAS communications director Athena Dinar told Live Science.

"The growth of both cracks during the last Antarctic winter has increased concern," Dinar said: "If [BAS] staff were to over-winter at the station and a calving event took place, there are no aircraft or ships in the vicinity to bring our staff out," Dinar said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cracks in the ice

Halley VI is usually staffed over the winter by a team of 14 scientists and technicians, who continue to gather data from experimental instruments and keep the station facilities operating during the punishing Antarctic winter storms.

Those staff who were scheduled to overwinter at Halley VI in 2018 will be redeployed to other BAS Antarctic stations or sent home to the U.K., according to the BAS statement.

"What we are witnessing is the power and unpredictability of Nature," said the BAS director Jane Francis. "The safety of our staff is our priority in these circumstances. Our Antarctic summer research operation will continue as planned, and we are confident of mounting a fast uplift of personnel should fracturing of the ice shelf occur."

Until 2012, the major ice chasm that is now southwest of Halley VI had been dormant for at least 35 years. But it became active again in that year and has since grown by an average of 1 mile (1.7 kilometers) every year since, according to BAS glaciologists.

After the Halloween Crack to the north of the station appeared in October 2016 with a length of 13 miles (22 kilometers), the BAS decided to relocate Halley VI to a new site on the ice shelf where there was less chance of it being cut off by a calving event.

The BAS reported that the Halloween Crack has grown rapidly since it first appeared, and that it now extends for about 37 miles (60 kilometers) from the sea.

The Halley VI modules are equipped with skis and are designed to be towed across the ice in case a relocation is necessary.

In early January, the BAS began towing the eight 10-ton (9-metric-ton) Halley VI modules to their new site about 14 miles (23 kilometers) inland from the old site — a 15-hour journey over the ice shelf for each module. [Album: Stunning Photos of Antarctic Ice]

Brief summery

Until the winter shutdown commences in March 2018, Halley VI will operate as normal at its new site on the Brunt Ice Shelf for the four months of the brief Antarctic summer season.

The base is currently being "defrosted" by technicians after its eight-month winter shutdown, to prepare it for occupation by 73 BAS staff who were heading to Antarctica this week, Dinar said.

"Halley is primarily a data factory, where we collect data on the space environment and monitor the atmosphere, [such as] ozone and CO2," she said.

There have been six Halley research stations on the Brunt Ice Shelf since the first, Halley I, was founded in 1956. In 1985, scientists based at Halley IV — the fourth BAS research station on the ice shelf — discovered Antarctica's "ozone hole," a patch of ozone-depleted air in the upper atmosphere that worsens during each southern-polar spring.

Subsequent research linked the ozone hole to the accumulation of chlorine-based chemicals in the upper atmosphere, such as the chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) once widely used as refrigerants and in aerosol cans. That research spurred the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement in 1987 that aimed to eliminate the use of CFCs and other ozone-depleting chemicals.

The latest studies of the Antarctic ozone hole show that it is now at its smallest extent since 1988, in part due to higher than normal temperatures over the southern polar continent.

When this summer's scientific program at Halley VI is completed in March 2018, the station will be shut for the long polar winter. The BAS reported its science and engineering teams have been working on ways to continue to collect data over the winter, which include relocating some scientific instruments and developing automated data capture technologies.

The conditions on the Brunt Ice Shelf, including the major ice cracks that are the reason for the relocation and seasonal shutdown, would also be monitored by satellite over the winter, Dinar said.

Despite the growing ice cracks, it is unlikely that Halley VI will to be moved again soon: "We are not going to move the station any further," the BAS director of science David Vaughan, told the U.K.'s The Guardian. "We believe that the station is actually in the optimal place on the ice shelf now."

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.