Aerial Images May Unlock Enigma of Ancient Stone Structures in Saudi Arabia

David Kennedy is emeritus professor of Roman Archaeology and History at the University of Western Australia and honorary research associate at the University of Oxford. He also founded the Aerial Photographic Archive for Archaeology in the Middle East (APAAME) in 1978 and has been co-director of the Aerial Archaeology in Jordan (AAJ) project since 1997. Kennedy contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Hundreds of thousands of stone structures that date back thousands of years and dot the deserts and plains of the Middle East and North Africa are, in many cases, so large that only a bird's-eye view can reveal their intricate archaeological secrets: gorgeous and mysterious geometric shapes resembling a range of objects, from field gates, to kites, to pendants, to wheels.

These are the "Works of the Old Men," according to the Bedouin when first questioned in the 1920s. And although ancient peoples evidently had their reasons for constructing these stone structures, their purpose has remained relatively opaque to archaeologists today.

I have been studying these Works for two decades, and their inaccessibility has made these sites' purposes even more elusive. That's where satellite imagery (used by Google Earth) and aerial reconnaissance, which involves much lower-flying aircraft) come in.

In the past few weeks, a huge opportunity opened up in this field after Live Science published an article about my research, sparking a deluge of international media coverage. Ultimately, I was invited to visit the country that has been least open to any form of aerial surveys, or even to archival aerial images: Saudi Arabia. Last month, they lifted this veil of sorts and allowed me to fly over the country's vast array of archaeological sites for the first time. [See Spectacular Images of the Stone Structures of Saudi Arabia]

Windows from Google Earth

Between the last years of World War I and roughly the early 1950s, some aerial archaeology was carried out in the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) that were ruled or controlled by Britain and France. Most famously, these archaeologists included Antoine Poidebard in Syria, Sir Aurel Stein in Iraq and Transjordan, and Jean Baradez in Algeria. Then, it ended as these countries achieved independence, and except by Israel from time to time, no further aerial reconnaissance for archaeology was carried out, and access even to archival aerial photographs in every MENA country was rarely possible. For half a century, archaeologists working in this extensive region, with its rich heritage, had to do so without the benefit of the single most important tool for prospection, recording and monitoring, much less the valuable perspective the aerial view revealed.

That situation began to change in 1995, when President Bill Clinton ordered the declassification of old CIA satellite imagery. But things changed more rapidly about a decade ago, when the far superior Google Earth's (and, to a degree, Bing Maps') seamless photomap of the entire globe became available. Initially, there were few "windows" of high-resolution imagery displayed for any of these countries, but by 2008, there were enough for archaeologists to use regularly, and increasingly easily.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

At a stroke, one strand of remote sensing was democratized: Anyone, anywhere with a computer and internet connection could traverse previously hidden landscapes on a photomap and see places perhaps long known to the local inhabitants but never formally defined and recorded in the databases of the national antiquities authorities. Into this space stepped a group of interested and talented amateurs for one of the countries for which aerial photographs had never been generally available: the 770,000 square miles (2 million square kilometers) of Saudi Arabia. Abdullah al-Sa'eed, a medical doctor, and colleagues of what they called The Desert Team, based in Riyadh, began to explore, via Google Earth, the huge lava field of western Saudi Arabia, called the Harret Khaybar. Then, they visited a variety of sites on the ground that they had discovered through the satellite imagery. In 2008 Dr al-Sa’eed contacted me and we collaborated on an article. [See More Images of the Gates and Other Stone Structures in Saudi Arabia]

Since al-Sa'eed and I published our findings about the stone structures of Harret Khaybar, I have published several articles on the archaeological remains in these lava fields of Arabia as a whole. There are immense numbers of them (at least hundreds of thousands), and each one can be huge (hundreds of metres across). Often, they are enigmatic, as there is no consensus on the purpose of several types of these structures. And they are almost entirely unrecorded and barely acknowledged; the extensive archaeological landscapes were first reported in the 1920s (for Jordan and Syria), but only now are they coming into sharp focus in terms of scale and significance.

Although these stone structures are found extensively in the northernmost harrat — the Harret al-Shaam, stretching from southern Syria across the Jordanian Panhandle and into Saudi Arabia — they appear in equally large numbers in most of the harrat stretching down the west coast of the Arabian Peninsula. It is those harrat in Saudi Arabia that have attracted much recent attention, in part because of their unfamiliarity and the astonishing numbers and types of sites that have emerged, some quite different from those long known in Jordan. [See Photos of Wheel-Shaped Stone Structures in the Middle East]

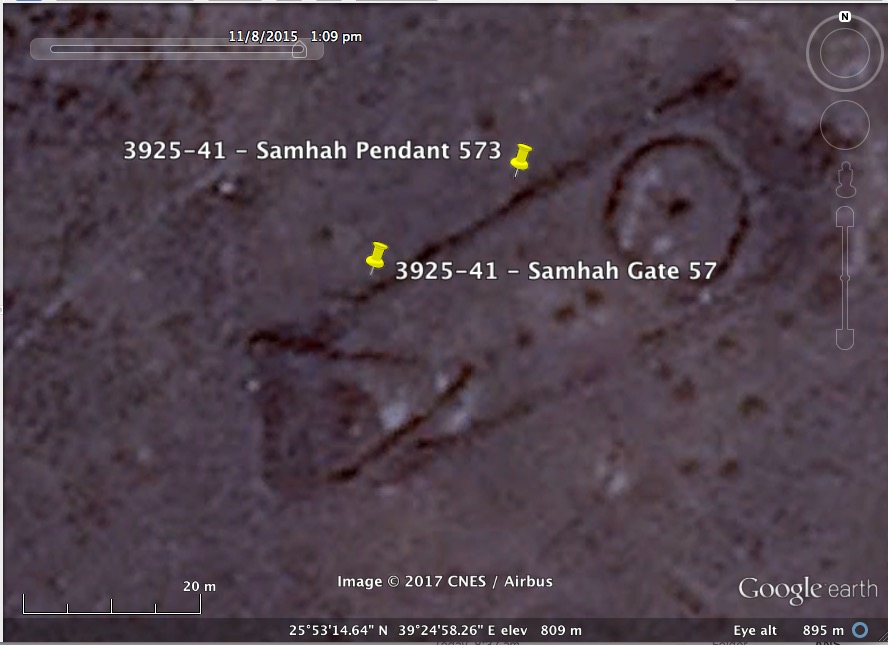

My own research on Saudi Arabia since 2009 has focused on a group of harrat in the northwest of the country, where I discovered a high-resolution "window" of pendants, wheels and cairns in the Harret Rahat, northeast of Jeddah; 917 kites in the Harret Khaybar; almost 400 gates, largely in the Harret Khaybar area; and a variety of site types found in various lava fields. All of these discoveries were made using the imagery of Google Earth (with occasional supplements from Bing Maps).

The need for aerial reconnaissance

The number of high-resolution "windows" on Google Earth has increased rapidly, especially since the launch of the Landsat 8 satellite in February 2013. These virtual "windows" are marvelous tools for fulfilling the traditional roles of conventional aerial reconnaissance, which has led many to pose a question: Why do we need aerial reconnaissance now that we have free access to the satellite imagery of Google Earth? [15 Secretive Places You Can Now See on Google Earth]

Of course, Google Earth will remain a useful tool for prospection; it is simple to "pin" and catalog sites, measure them, sketch them and generate distribution maps for interpretation. The limitations are equally obvious, however. The imagery is two-dimensional, and even the best resolution can be very fuzzy when enlarged. Detail is missing, and some sites are effectively invisible for various reasons. And imagery may be months, or even years, old and thus less valuable for routine monitoring of development.

In short, traditional low-level and usually oblique aerial photography continues to have several advantages and uses: It is immediate, if there is a regular flying program; it can be timed to maximize solar and climatic conditions; the oblique view provides an extra dimension to the "flatness" of Google Earth; the high-quality camera photograph from a low altitude reveals details of structures not visible on Google Earth; and with a helicopter as the platform, it is possible to land and obtain ground data immediately for sites that may otherwise be too remote for easy access.

This last point is important: As has always been the case, it is vital that aerial reconnaissance (and interpretation of satellite imagery) be paired with as much ground inspection as possible. Ideally, all three techniques (aerial surveys, satellite imagery and ground inspection) would be used.

In recent years, that ideal situation has been possible in just one MENA country — Jordan — thanks to generous support from its government and from the nonprofit Packard Humanities Institute, which is dedicated partly to archaeology. Since 1997, aerial photos have been taken as part of my project called Aerial Archaeology in Jordan (AAJ), and over 100,000 aerial photographs have been made available for research in an archive (APAAME) established in 1978.

A game-changer in my research happened when the interest sparked by the Live Science article led to my invitation to study these structures in one region of – till now, the least open of these Middle Eastern countries, regarding reconnaissance.

Aerial archaeology in Saudi Arabia

Some of Saudi Arabia's neighbors looked for archaeological sites with aerial reconnaissance before World War II, but even aerial photographs from surveys of this immense kingdom were almost entirely unavailable. Of course, archaeologists knew the kingdom was home to high-profile sites as well as great cemeteries of thousands of tumuli.

As Google Earth has opened a new and extensive area for research, it has indirectly helped to spark a trial season of aerial reconnaissance for archaeology. There is now the possibility that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia will become the second MENA country to support a regular program of aerial archaeology to find, record, monitor and research the hundreds of thousands of sites in the country. [25 Strangest Sights on Google Earth]

On Oct. 17, Live Science published an article describing a highly unusual type of site – called gates in the Harret Khaybar area, that my colleagues and I had systematically catalogued and mapped and were to publish in the scientific literature in November. That sparked immediate and extensive international media coverage, including features in The New York Times, Newsweek and the National Geographic Education Blog. Four days after the article was published on Live Science, I got an invitation from publication from the Royal Commission for Al-Ula, in northwest Saudi Arabia, to visit that town. The Al-Ula oasis is famous for hosting the remains of a succession of early cultures and more recent civilizations, all strewn thickly among its 2 million-plus date palms. As a Roman archaeologist, I had known this oasis for over 40 years as the location of Madain Salih, Al-Hijr — ancient Hegra, a world-class Nabataean site adopted by UNESCO.

The expansive area includes thousands of rock-cut tombs and graves — most notably, scores of monumental tombs cut into the rock outcrops of the plain and evoking those of the capital, Petra, about 300 miles (500 kilometers) to the north. After the Roman annexation of the Nabataean kingdom in A.D. 106, a garrison was installed. Some of thesetrooops left their names and units in Latin, as graffiti on a rock outcrop. More recently, a Saudi-French archaeological team recovered a monumental Latin inscription recording construction around A.D. 175 to 177 under Emperor Marcus Aurelius, as well as part of the defenses and barracks of the Roman fort inserted into the town. Not far off are the ruins of the city of Dedan, mentioned in the Hebrew Bible and the remarkable "library" of monumental Lihyanite inscriptions and art carved onto rocks and the cliff face.

However, the objective of my visit lay in the lava fields in the wider region. Helicopter flights could give access to the extensive Harret Uwayrid (and contiguous Harret Raha) to the west, stretching some 77 miles (125 km) and rising to an elevation of about 6,300 feet (1,920 meters), much of which could be viewed only from the air. The most recent volcanic eruption occurred in A.D. 640, but the hundreds of sites I had already "pinned" there on Google Earth were evidently far older, most likely prehistoric and a component of the "Works of the Old Men" that I'd encountered in other harrat.

We were also able to fly over the Harret Khaybar and view not just the gate structures but also the kites, pendants, keyholes and much more we had seen on the Google Earth imagery.

Four days after the invitation from the Royal Commission, my colleague Don Boyer, a geologist who now works in archaeology, and I were on our way to Riyadh. Almost immediately, on Oct. 27 to Oct. 29, we began three days of flying in the helicopter of the Royal Commission. In total, we flew for 15 hours and took almost 6,000 photographs of about 200 sites of all kinds — but mainly the stone structures in the two harrat.

Though we didn't have much notice, Boyer and I spent three days before our visit looking over the sites we had "pinned" and catalogued using Google Earth over several years. We then, relatively easily, planned where we wanted to fly in order to capture several thousand structures in these two lava fields. Our helicopter survey was probably the first systematic aerial reconnaissance for archaeology ever carried out in Saudi Arabia. It was possible only because of the publication of the Live Science feature article describing my research on the gate structures, and the resulting international media coverage, which caught the attention of the Royal Commission.

The latter is significant: Several recent interviews and feature articles in the international media have highlighted the drive of the young Crown Prince to open up his country to development and innovation. The Royal Commission for the city of Al-Ula, an internationally important cultural center for the region that boasts world-class archaeological sites, is one element of this openness. Development is likely to be rapid, and the commission is open to engaging with international experts in its wider project to find, document and interpret the hundreds of thousands of surviving sites. Collaboration with local inhabitants, who know of even the more remote sites, and local archaeologists will be vital to this effort.

Happily, on our flights, we were accompanied by Eid al-Yahya, an archaeologidst, author and expert of Arab culture, who has traversed swaths of these harsh but archaeologically rich landscapes over 30-plus years and has explored many individual sites. Even just the archaeological component of this grand project of the commission comprises several components. One component — and, arguably, one of the most pressing — is to help the commission understand its wider heritage record: where and what, and then when and why.

Because the area is so immense — encompassing some 10,000 square miles, or 27,000 square km — this is a task for remote sensing. This method will be combined with several techniques: the interpretation of Google Earth imagery systematically, the cataloging of the sites located, complementary low-level aerial reconnaissance and photography, and associated ground investigation. We have been interpreting Google Earth imagery for some years. The ground investigation, by contrast, is in its infancy. The aerial reconnaissance part has made a good start over the past few weeks and deserves to be pursued urgently. Based on the 20 years of aerial archaeology research we have conducted in Jordan, my co-director Dr. Robert Bewley and our team can offer our expertise for this last task.

A successful systematic program of aerial archaeology in the Al-Ula region could provide valuable lessons and establish best practices for the far larger task of mapping the archaeology of Saudi Arabia, and those efforts may be assisted by partnerships with the Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa project at Oxford University.

Kennedy's recent books include: "Ancient Jordan from the Air" (with R. Bewley, 2004), "Gerasa and the Decapolis" (2007), "Settlement and Soldiers in the Roman Near East" (2013) and an eBook "Kites in 'Arabia'" (with R. Banks and P. Houghton, 2014). In progress are books on the Hinterland of Roman Philadelphia and Travel and Travellers East of Jordan in the 19th Century.

Original article on Live Science.