New Blood Pressure Numbers: 130 Is Now High, Doctors Say

ANAHEIM, Calif. — The bar for what's considered "high blood pressure" just got lowered, meaning millions more Americans will now be classified as having the condition, according to new guidelines from several leading groups of heart doctors.

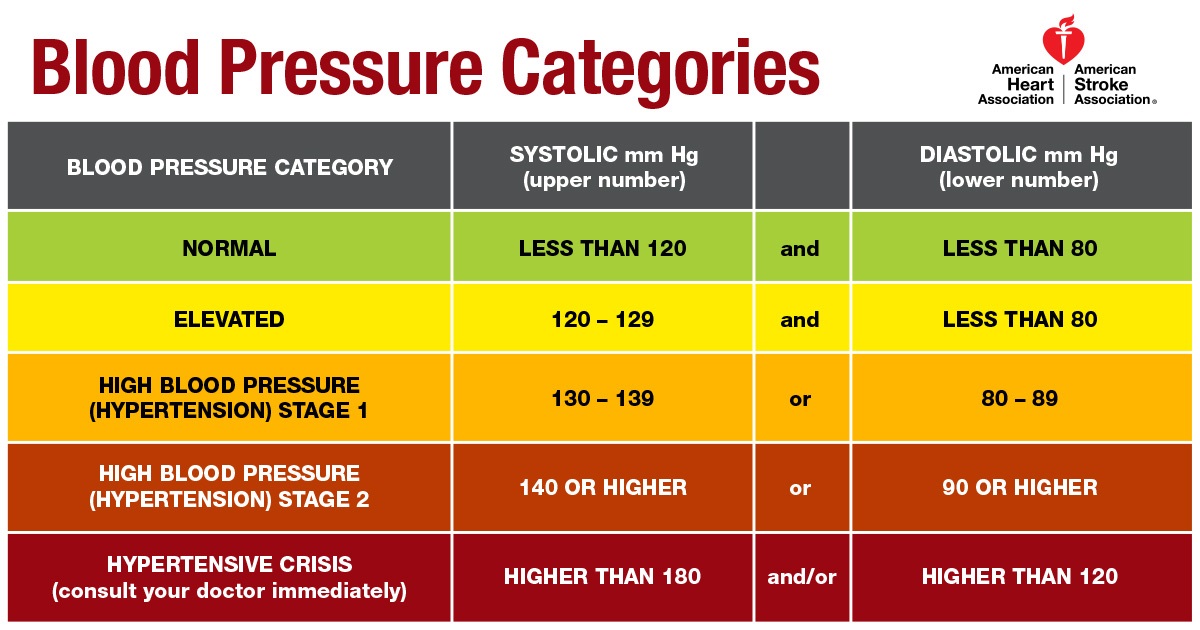

The guidelines, from the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC), now define high blood pressure as 130 mm Hg or higher for the systolic blood pressure measurement, or 80 mm Hg or higher for the diastolic blood pressure measurement. (Systolic is the top number, and diastolic is the bottom number, in a blood pressure reading.) Previously, high blood pressure was defined as 140 mm Hg or higher for the systolic measurement and 90 or higher for the diastolic measurement.

The findings mean that an additional 14 percent of U.S. adults, or about 30 million people, will now be diagnosed as having high blood pressure, compared with the number diagnosed before the new guidelines. This will bring the total percentage of U.S. adults with high blood pressure to 46 percent, up from 32 percent previously. [9 New Ways to Keep Your Heart Healthy]

However, the guidelines stress that, for most of the newly classified patients, the recommended treatment will be lifestyle modifications, such as weight loss and changes in diet and exercise levels, as opposed to medications. Only a small increase in the percentage of U.S. adults receiving blood pressure medications — about 2 percent — is expected, the authors said.

Lower is better

"There is a growing body of evidence that lower blood pressure is better for your health," Dr. Steven Houser, the immediate past president of the American Heart Association, said here today (Nov. 13) at a news conference announcing the new guidelines.

The guidelines "[reflect] this new information and should help people prevent, diagnose and treat high blood pressure sooner," Houser said. "We saw the needs to update these guidelines to reflect the real threats of high blood pressure."

The new guidelines are based on a rigorous review of nearly 1,000 studies on the subject, which took the authors three years to complete.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new guidelines now classify people's blood pressure measurements into the following categories:

- Normal: Less than 120 mm Hg for systolic and 80 mm Hg for diastolic.

- Elevated: Between 120-129 for systolic, and less than 80 for diastolic.

- Stage 1 hypertension: Between 130-139 for systolic or between 80-89 for diastolic.

- Stage 2 hypertension: At least 140 for systolic or at least 90 mm Hg for diastolic.

(The new guidelines eliminate an older category of "prehypertension," which was used for people with systolic blood pressure between 120-139 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure between 80-89 mm Hg.)

The findings touch on an issue that has been under debate in the medical community: Exactly how low should patients aim to go when reducing blood pressure levels. Several recent studies suggest that lower blood pressure targets — even lower than previously recognized — had substantial health benefits for patients.

For example, a 2015 study known as the SPRINT trial found that patients who lowered their systolic blood pressure to around 120 mm Hg were 27 percent less likely to die during the study period, compared with those whose treatment target was to lower their blood pressure to less than 140 mm Hg. (The SPRINT study made headlines in 2015 when the trial was abruptly cut short because the findings were so significant.)

Researchers also now know that people with a blood pressure between 130-139/80-89 mm Hg have double the risk of cardiovascular complications, compared with those with normal blood pressure, said Dr. Paul Whelton, a professor of global public health at Tulane University and lead author of the guidelines.

“We want to be straight with people — if you already have a doubling of risk, you need to know about it," Whelton said in a statement. "It doesn't mean you need medication, but it's a yellow light that you need to be lowering your blood pressure."

Treating hypertension

The new guidelines recommend that doctors only prescribe blood pressure medication for patients with stage I hypertension if they have already had a cardiovascular "event" such as a heart attack or stroke; or if they are at high risk for a heart attack or stroke based on other factors, such as the presence of diabetes, the authors said.

People with stage 1 hypertension who don't meet these criteria should be treated with lifestyle modifications. These include: starting the "DASH" diet, which is high in fruit, vegetables and fiber and low in saturated fat and sodium (less than 1,500 mg per day); exercising for at least 30 minutes a day, three times a week; and restricting alcohol intake to less than two drinks a day for men and one drink a day for women, said vice chairman of the new guidelines, Dr. Robert Carey, a professor of medicine and dean emeritus at the University of Virginia Health System School of Medicine. [6 Healthy Habits Dramatically Reduce Heart Disease Risk in Women]

Carey hopes the new guidelines will "cause our society and our physician community to pay attention much more to lifestyle recommendations."

Stage 2 hypertension should be treated with a combination of lifestyle modifications and blood pressure medications.

Some people may ask why doctors are lowering the threshold for high blood pressure, when it was already difficult for many patients to achieve the previous blood pressure targets of below 140 mm Hg/90 mm Hg, said Dr. Pamela B. Morris, a preventive cardiologist and chairwoman of the ACC's Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Leadership Council. However, Morris said that the guidelines were changed because "we now have more precise estimates of the risk of [high] blood pressures," and these new guidelines really communicate that risk to patients. So, just because it's going to be difficult for people to achieve, "I don't think it's a reason not to communicate the risk to patients, and to empower them to make appropriate lifestyle modifications," Morris told Live Science.

Dr. Rachel Bond, associate director of the Women's Heart Health Program at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, who was not involved with the guidelines, said she agreed with the new updates. "I believe this will allow for earlier detection [of high blood pressure], and allow for more lifestyle modification to prevent the long-term detrimental effects of untreated high blood pressure," Bond said.

The guidelines also say that a patient's blood pressure levels should be based on an average of two to three readings on at least two different occasions. It's also reasonable for doctors to screen for "white-coat hypertension," which occurs when blood pressure is elevated in a medical setting but not in everyday life, the authors said. This can be done by having patients measure their blood pressure at home.

Bond said she also agreed with these guidelines, and noted that she has worked to educate her medical staff on the proper methods for obtaining blood pressure "rather than hastily checking a number which has a huge impact on our patients' medical care."

Dr. Ragavendra Baliga, a professor of internal medicine at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, called the new guidelines a "tour-de-force."

"Given there is more up-to-date data on the impact and significance of hypertension…this ACC/AHA guideline is timely and comprehensive," said Baliga, who was not involved with the guidelines. Baliga added that he thought the new targets should be achievable with a combination of lifestyle modifications and medications.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.