Humans Have Cracked the Secrets of Uncrackable Parrotfish Teeth

Have you ever dug your feet into the warm, soft surface of a white sand beach? Felt the fine, dry grains slide pleasurably between your toes? Thank a parrotfish. Specifically, thank it for its poop. Most of the sand on just about every white beach in the world is the product of generations of the strange family of fish digging their sturdy beaks into ocean-floor coral and chewing chunks of rocky organic matter down to powder. And now, researchers know how the swimming weirdos get through their stony meals without cracking their teeth.

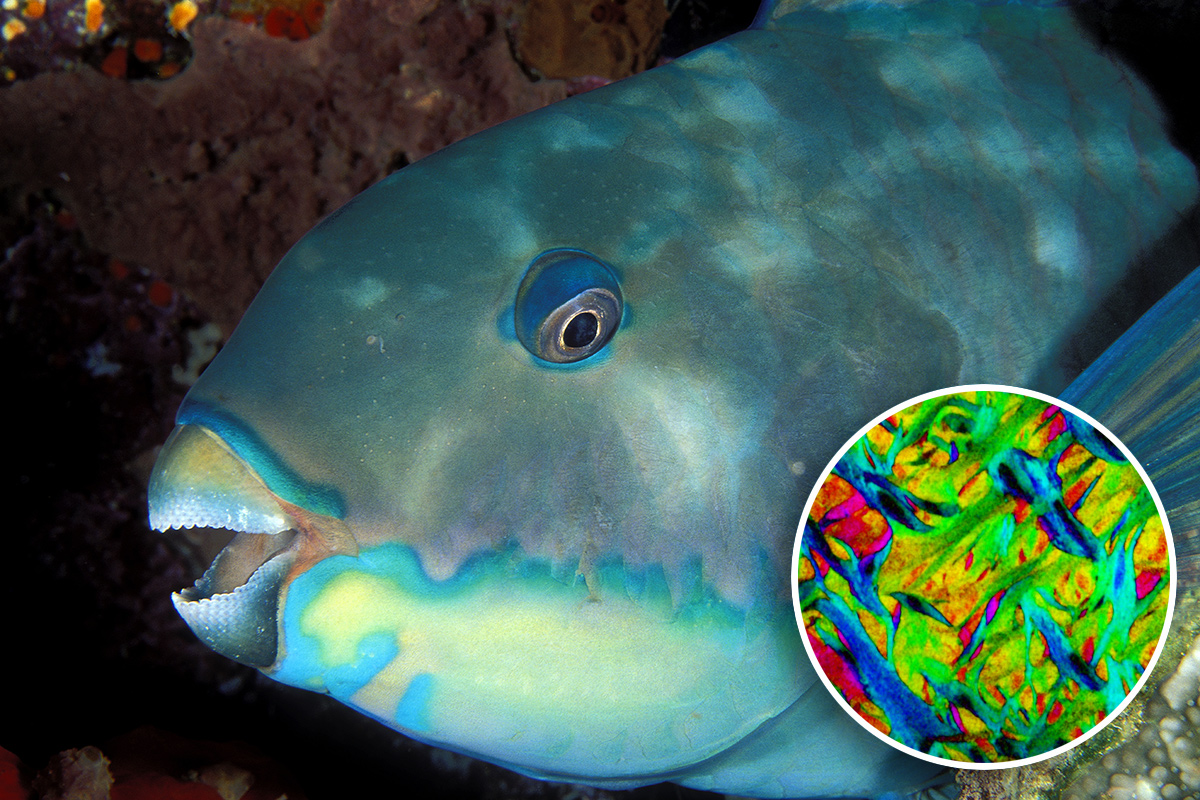

A team of scientists from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Nanyang Technological University in Singapore and the University of Wisconsin-Madison subjected parrotfish beaks to a Berkeley X-ray machine known as the Advanced Light Source (ALS). The ALS can image organic crystals at a microscopic level. And the analysis revealed a unique woven structure in the crystals in a parrotfish's mouth that could open new frontiers for materials science, the researchers said.

"Parrotfish teeth are the coolest biominerals of all," Pupa Gilbert, a UW-Madison physicist and lead author of the study, said in a statement. "They are the stiffest, among the hardest, and the most resistant to fracture and to abrasion ever measured." [See Photos of the Bizarre Bumphead Parrotfish]

"Stiffness" and "hardness" may sound like synonyms, but they have different meanings in engineering. A stiff object isn't very elastic. Press on it, and it won't bend; pull your finger away, and the material won't bounce back. A hard object resists permanent damage; bash it against a wall, and it won't dent or deform.

The record-stiff, superhard teeth of parrotfish apply enormous force — 530 tons of pressure per square inch — to their coral meals. And those teeth don't break or fall out of the animals' mouths.

And yet, there isn't anything all that chemically interesting about parrotfish teeth, the scientists said. Look at them under a microscope, the researchers explained in their statement, and you'd struggle to differentiate the material from the enamel found in the mouths of all kinds of animals.

Parrotfish have about 1,000 teeth arranged in 15 rows, with new teeth constantly bursting from the soft tissue to replace old ones. That's not all that unusual; many sharks have a similar setup. But parrotfish are unique in the way their legions of teeth fuse together to form their hard beaks.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The real astonishing structure of parrotfish beaks, though, is much smaller, as the researchers said in a paper published online Nov. 15 in the journal ACS Nano.

On the micro scale, the enamel fibers' diameters narrow from an average of 5 microns (5 thousandths of a millimeter) at the bases of the teeth to 2 microns (2 thousandths of a millimeter) near the tips. And the fibers weave together like tight fabric out of a loom, warp and weft aligned at right angles to one another.

That structure, like the one likely holding your shirt together but spun from hard organic crystals, gives parrotfish the superpower of chewing on rock-hard, brittle corals the way you'd bite into a loaf of bread.

Researchers said they might be able to mimic the micro-structure to build synthetic materials for human use. Imagine a set of tools capable of surviving the grinding pressure of 530 tons per square inch against rough, hard coral. It's the biological technology behind every white beach in the world. Who knows where it will go next?

Original article on Live Science.