Climate Partly to Blame for German Migration to America in 19th Century

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

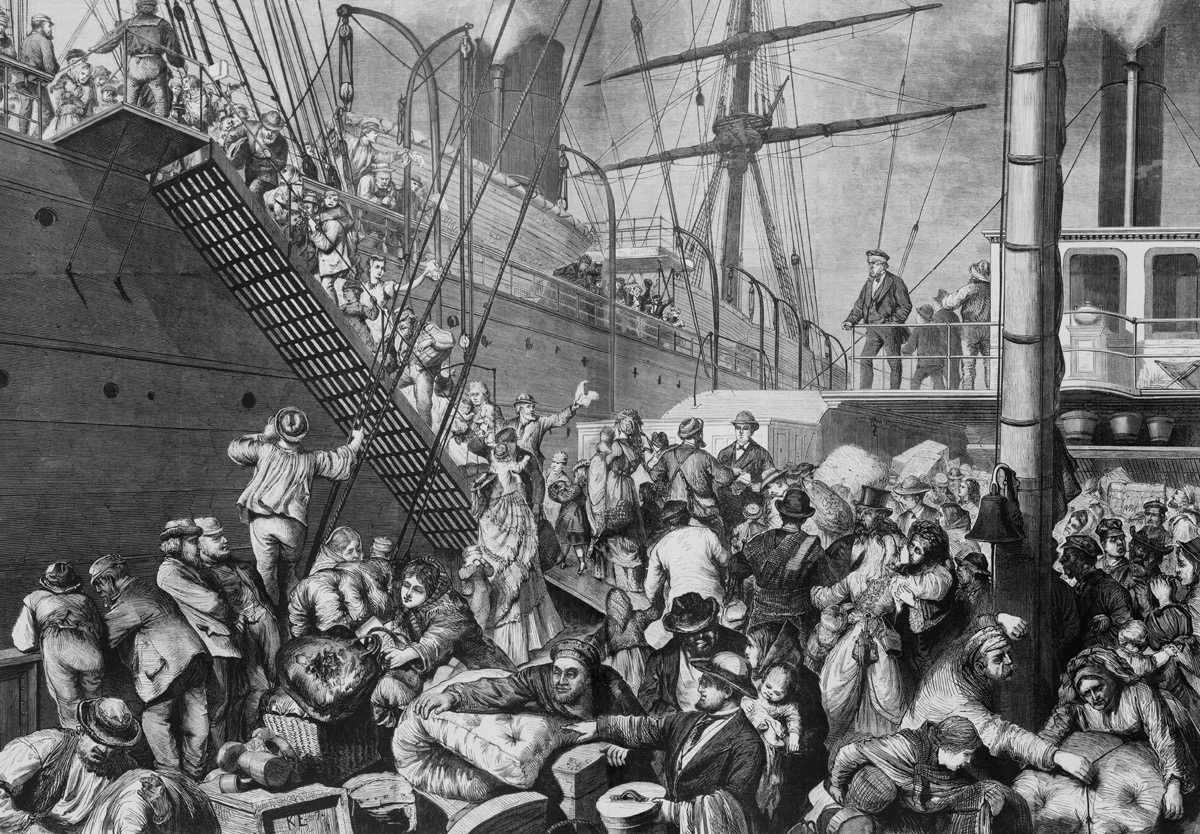

Today, Germany is a top migration destination, second only to the United States. But in the 19th century, Germans were fleeing their homeland in huge numbers in search of better prospects abroad.

More than 5 million Germans moved to North America during that era, including the ancestors of Donald Trump and the Heinz family. And now, new research shows that climate was a major factor driving this migration pattern.

"Up until today, the migration from Europe into North America was the largest migration in history," said Rüdiger Glaser, a professor of geography at the University of Freiburg, Germany. Most of the literature on the migration out of Germany usually attributed this phenomenon to political and social issues, Glaser said. [Refugee Crisis: Why There's No Science to Resettlement]

The 19th century was indeed a time of major political and social upheavals in Germany, from the warfare of the Napoleonic era, to the bourgeois revolution of 1848, to the industrial revolution, to the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. But Glaser and his colleagues wanted to test a hypothesis that climate might have been an important factor setting some of this mass migration into motion, using statistical models.

The researchers focused on the region around their university —now the state of Baden-Württemberg in southwestern Germany —which had thorough 19th-century records for migration, population, weather, harvest yields and cereal prices. (This area was not Germany as we know it today; in 1815, the beginning of the study timeframe, it was a patchwork made up of the Grand Duchy of Baden, the Kingdom of Württemberg and the Kingdom of Prussia.)

They used a complicated statistical model to try to quantify the effect of climate on migration. Overall, Glaser said that about 30 percent of the migration out of that corner of Germany between 1815 and 1886 could be explained by a chain of events that starts with climate: Poor climate conditions lead to low crop yields, which lead to rising cereal prices, which lead people to want to pick up and leave for better opportunities. [10 Surprising Ways Weather Has Changed History]

"It's quite clear," Glaser said. "This chain effect is convincing."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This isn't surprising when you consider that the majority of the population in southern Germany at that time was rural, with household livelihoods and incomes tied very closely to agricultural productivity," said Robert McLeman, an associate professor at Wilfrid Laurier University in Canada, who wasn't involved in the study.

McLeman said that people tend to associate environmental migration with environmental refugees, or large numbers of people suddenly displaced from their homes by storms, floods and single big events. "While such events do indeed occur periodically, we often overlook the longer-term, more subtle influence climate and environment have on migration patterns," McLeman told Live Science. He added that the report shows "how climate also influences migration indirectly, by affecting market prices for commodities and undermining household livelihoods."

Glaser and his colleagues found some spikes in migration tied to particularly severe climate events. The massive 1815 eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia, for example, sent enough volcanic ash into the atmosphere to cause global disruptions. 1816 was dubbed the "Year Without a Summer," as farmers across the Northern Hemisphere experienced poor harvestscausing food prices to rise.

Other emigration waves had clearer geopolitical influences. A spike in migration between 1850 and 1855 occurred during the Crimean War, the researchers found, when France banned food exports, which squeezed German grain markets. The authorities of Baden during this time tried to get rid of the poor (in part, hoping to prevent uprisings) by funding their emigration.

Lessons from 19th-century Germany can be drawn for other parts of the world where the majority of people depend on small-scale or subsistence agriculture, such as South Asia, the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, McLeman said.

"When crop productivity and rural household incomes are affected by adverse climate events and conditions, especially droughts, people in those regions can and do migrate, for many of the same reasons and motivations as did German farmers in the 19th century, especially when other factors like conflict and political instability occur simultaneously," McLeman said.

Glaser said he would like to apply the same methods to understand the effect of climate change on current migration patterns, though he added that it's a challenge to get reliable data sets from unstable parts of the world. Past research has already shown that climate-related events like droughts and severe storms caused food shortages in 2010 which may have contributed to the Arab Spring in the Middle East and North Africa.

"The climate change issue as a whole will lead to more pressure in regions of the world where we already have an unstable situation," Glaser said.

The study was published today (Nov. 21) in the journal Climate of the Past.

Original article on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus