Evidence Mounts Against So-Called Climate Change Hiatus

Evidence is mounting against the so-called climate change hiatus — a period lasting from 1998 to 2012 — when global temperatures allegedly stopped rising as sharply as they had before. This misconception can be explained, in part, by missing temperature data from the Arctic, a new study finds.

That seeming pause in rising global temperatures had been used as evidence by climate skeptics to suggest that the Earth wasn't really warming at an unnatural pace.

To get around the data gap, researchers from the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) and China created the first global data set of surface temperatures. They filled in the missing puzzle piece with data taken from buoys drifting in the Arctic Ocean during the so-called global warming hiatus, the researchers said. [6 Unexpected Effects of Climate Change]

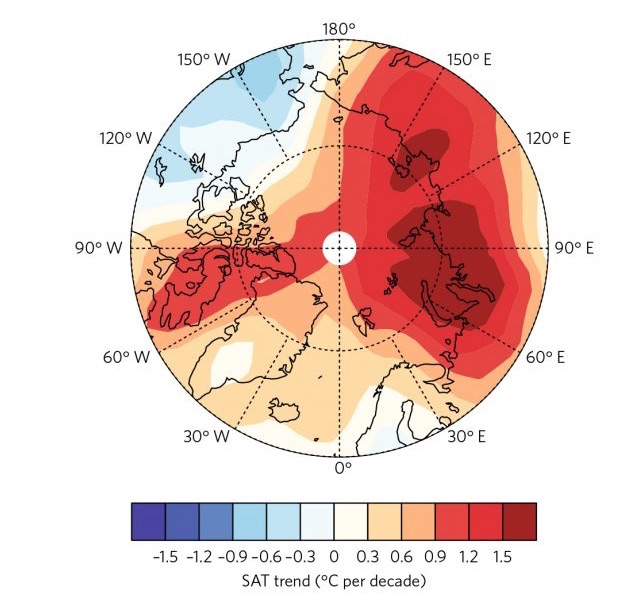

"We recalculated the average global temperatures from 1998 to 2012 and found that the rate of global warming had continued to rise at 0.112 degrees Celsius [0.2 degrees Fahrenheit] per decade, instead of slowing down to 0.05 degrees C [0.09 degrees F] per decade as previously thought," study co-researcher Xiangdong Zhang, an atmospheric scientist with UAF's International Arctic Research Center, said in a statement.

The new estimates reveal that the Arctic heated up rapidly during this period — more than six times the global average, said Zhang, who is also a professor with UAF's College of Natural Science and Mathematics.

Mind the gap

The reason for the data gap is simple: The remote Arctic doesn't have a robust network of instruments that collect air temperature data, the researchers said.

To fill in the gap, the team used temperature data collected from the University of Washington's International Arctic Buoy Programme, which allowed them to reconstruct Arctic surface air temperatures from 1900 to 2014, the researchers wrote in the study. The researchers also used newly corrected worldwide sea-surface temperature data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. (Government temperature datasets are corrected, that is, vetted, before their official release, Live Science previously reported.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers incorporated the Arctic information with the global data. Then, they re-estimated average global temperatures from 1998 to 2012 with more accurate and representative data, Zhang said.

The hiatus

The hiatus is a controversial topic among climate scientists. At the time and following the hiatus, many researchers acknowledged that temperature data indicated that the Earth was still warming, but not as rapidly as it had prior to that 14-year stint. Climate change doubters seized on these findings, using the pause as evidence to show that man-made climate change wasn't real, Live Science previously reported.

Over the past century, Earth's average temperature has increased as human-made technologies emitted more greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, that linger in the atmosphere and trap heat.

That's why the so-called global-warming hiatus confounded scientists. Some researchers suggested that the unusually warm 1997 to 1998 El Niño, and a long period afterward without an El Nino in the tropical Pacific Ocean might have diminished the rate of global warming.

However, the new findings show that this pause didn't happen after all, the researchers said. Moreover, the study shows that Arctic temperature data is key when calculating climate change. Until recently, many scientists didn't think that the Arctic was large enough to greatly influence average global temperatures, Zhang said.

"The Arctic is remote only in terms of physical distance," he said. "In terms of science, it's close to every one of us. It's a necessary part of the equation and the answer affects us all."

Another 2017 study, published in the journal Science Advances, also recently cast doubt on the so-called hiatus. That study showed that inconsistent water measurements helped lead to the hiatus misconception, Live Science reported.

The new study was published online Monday (Nov. 20) in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.