'Poop Pills' Work Just As Well As Traditional Fecal Transplants

"Poop transplants" given as a pill may work just as well as those delivered via colonoscopy, and the pill form may be a more pleasant treatment method for patients, a new study from Canada finds.

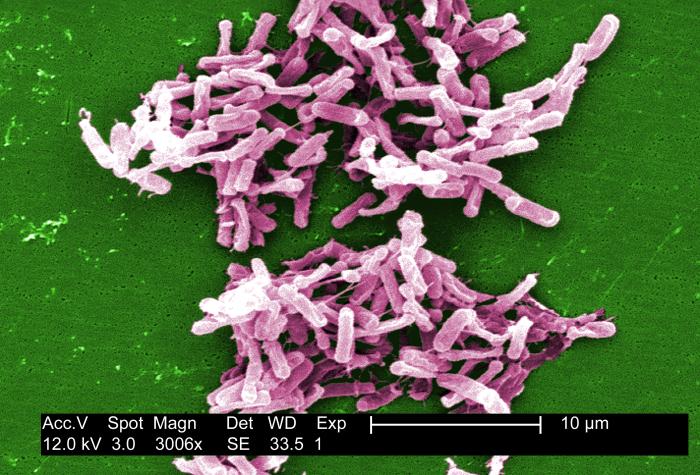

The medical name for these transplants is fecal microbiota transplantations (FMTs), but they're commonly referred to as poop transplants. They are used to help treat patients who suffer from Clostridium difficile (C. diff) bacterial infections, which cause severe diarrhea and inflammation of the colon, and can be notoriously difficult to treat.

During the procedure, feces from a healthy donor are mixed with water and transferred to the patient's colon through a tube. The idea behind the transplant is that the healthy donor feces can restore "good" bacteria levels in the gut. (C. diff flourishes when these healthy bacteria are wiped out.) [The Poop on Pooping: 5 Misconceptions Explained]

In the new study, published today (Nov. 28) in the journal JAMA, researchers compared the effectiveness of "poop pills" with the effectiveness of the standard fecal transplant procedure, in which the donor stool is delivered via colonoscopy, in patients with chronic C. diff infections. The study found that swallowing the capsule, which contained frozen stool, worked just as well as the colonoscopy-administered treatment.

To compare the effectiveness of the two treatments, the researchers conducted a randomized clinical trial that included 116 patients with recurrent C. diff infection (CDI), meaning that the infection kept coming back despite treatment. Some of the participants received a poop transplant by taking a pill, while others received the transplant via colonoscopy.

The patients were enrolled in the trial between October 2014 to September 2016. Twelve weeks after the patients received the poop transplant, the researchers followed up with the patients to see if the infection had returned.

Overall, the results of the study found that taking a "poop pill" not only saved time and medical costs but was also considered a more "pleasant" treatment than a colonoscopy-based fecal transplant, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition, the researchers found that the "poop pills" were just as effective at reducing the risk of recurrent C. diff infections and increasing the diversity of patients' gut bacteria as the colonoscopy-based treatments, according to the study.

"Recurrent CDI was prevented after a single treatment in 96 percent of patients in both groups after 12 weeks," the researchers, led by Dr. Dina Kao, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Alberta in Canada, said in a statement. "More patients who received capsules rated their experience as 'not at all unpleasant.'"

Currently, there's no "universally accepted or validated treatment algorithm" for people with recurrent CDIs, according to an editorial published alongside the study in the same journal. Other treatment options to reduce the risk of recurrent CDI include taking an antibiotic called vancomycin for a long period of time, taking probiotics, or eating fermented foods such as kefir, wrote the editorial authors, led by Dr. Krishna Rao, an infectious-disease specialist at Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan.

Although "fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is an increasingly common treatment to address [recurrent CDI] … [the] widespread adoption [of the treatment] is limited in part by the logistics of delivering the stool product," the editorial said. Therefore, the study offers another possible treatment option for recurrent CDI, which affects more than 450,000 patients in the United States each year.

However, though the "data on FMT using [pills] are encouraging and may decrease barriers to further adoption of FMT for [recurrent CDI], many broader questions remain about" the effectiveness of poop transplants, the editorial authors wrote. For example, the success of FMT in patients with severe and complicated CDI, who were excluded from the clinical trial, remains a question to be studied, they wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.