'Hairy' Microbes Named for Rush Members Are Living in the Limelight

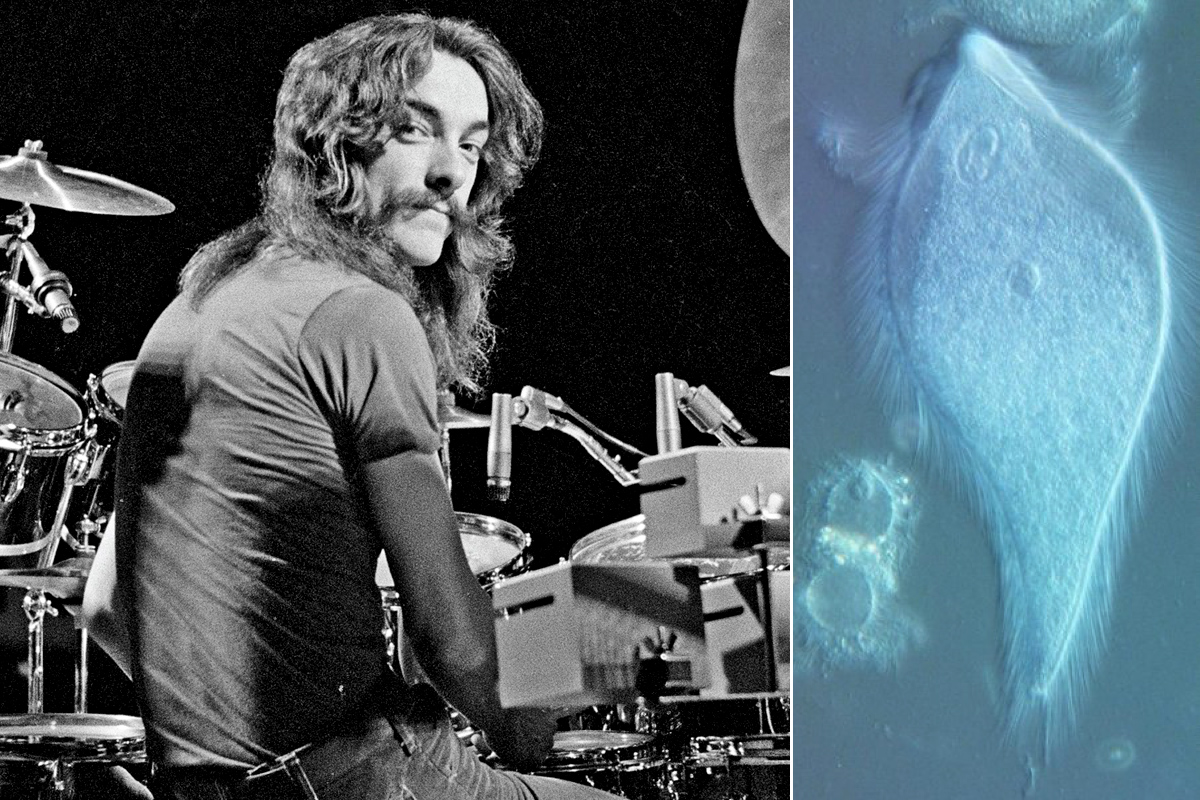

The cascading 1970s-era locks of musicians in the progressive-rock group Rush recently inspired a team of researchers to lend the rockers' names to a trio of microbes with flowing flagella that resemble the band members' hair.

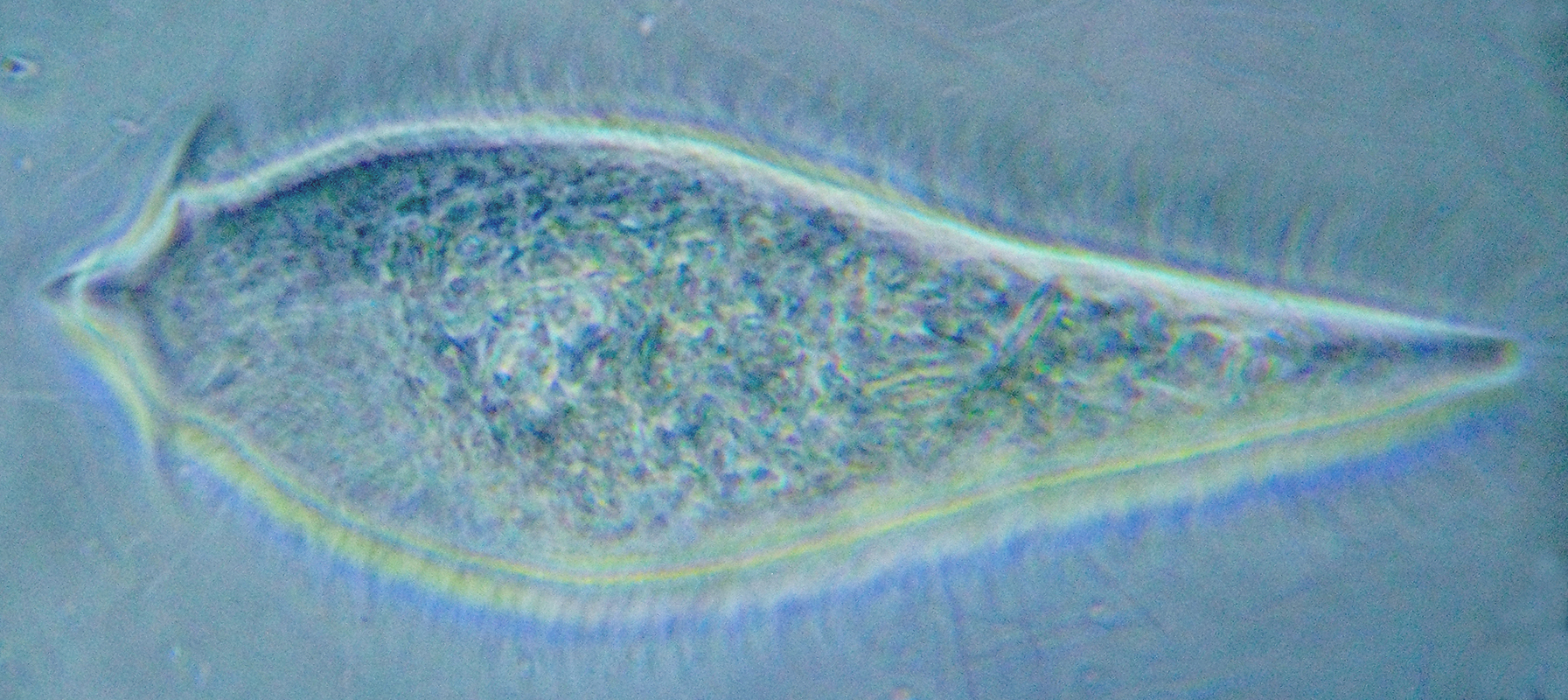

Unlike the Canadian band, the microbes are found in the guts of termites, where they help the insects digest compounds found in woody plants. They belong to the genus Pseudotrichonympha, which was first identified in 1910 and includes single-celled microbes, called protists, with a single nucleus and copious "hair" in rows over most of the cell body.

The three new microbe species — named for Rush singer and bassist Geddy Lee, guitarist Alex Lifeson and drummer Neil Peart — are Pseudotrichonympha leei, P. lifesoni and P. pearti, and were found in two species of termites from North America and Australia, according to a new study. [StarStruck: Species Named After Celebrities]

Patrick Keeling, the study's lead author and a microbiologist at the University of British Columbia — and a Canadian — had recommended that one of his co-authors listen to Rush as an example of "good Canadian music," Keeling said in a statement. When the team described the microbes, which were covered with long flagella, there were inevitable comparisons to photos of the long-haired Rush members on the cover of their album "2112," released in 1976.

Cells use flagella to propel themselves, and many have at least some of these hairlike structures. But these microbes were covered with flagella numbering in the thousands or tens of thousands, the study authors reported. Why the microbes are so "hairy" is uncertain, but it could have something to do with how they feed, Keeling told Live Science in an email.

"They are packed like sardines in the gut, so it's probably not for 'swimming,'" he wrote in an email. "I think it is to move the gut fluid around the protist cell, to give them access to the little chunks of wood they eat. So, they make currents in the gut fluid to bring the food to them." [Magnificent Microphotography: 50 Tiny Wonders]

Rush's heyday was decades ago, but the microbes' relationship with their termite hosts dates back quite a bit further, Keeling told Live Science. This microbe genus is found only in a certain termite group that diverged from other termites about 40 million years ago, so it would be "pretty safe" to define that relationship as at least 40 million years old, Keeling said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The universal dream

Naming a new species after a person not only allows scientists to show their admiration for a colleague or celebrity who inspired them but also attracts attention to the new find, serving as an important reminder of the vast number of species on Earth that are yet to be discovered.

Scientists' favorite musicians often appear in new species' names. In August, a Jurassic crocodile relative was named Lemmysuchus obtusidens, after the late Motörhead bassist and singer Ian "Lemmy" Kilmister. Other species have been named for the legendary guitarist Jimi Hendrix (a flowery succulent, Dudleya hendrixii), country singer-songwriter Johnny Cash (the tarantula Aphonopelma johnnycashi) and reggae superstar Bob Marley (parasitic crustacean Gnathia marleyi).

Species names can also reflect scientists' geeky interests, such as the extinct giraffe relative with unusual headgear named Xenokeryx amidalae, after Queen Amidala from the "Star Wars" prequels. [9 Animals with 'Star Wars'-Inspired Names]

World leaders have also received taxonomic honors: President Barack Obama inspired the names of a type of lichen (Caloplaca obamae), a trapdoor spider (Aptostichus barackobamai) and a brightly colored fish native to waters near Hawaii (Tosanoides obama).

But sometimes, scientists come across so many new species at once — as one team did when they discovered hundreds of undescribed weevil species in New Guinea in 2013 — that they simply resort to picking names at random from the phone book.

All the busy little creatures

Rush is known for lyrics that mine science-fiction and fantasy imagery but also incorporate elements of philosophy, literature and history. Some songs even have overtly scientific references, such as "Natural Science," written by the band for the 1980 album "Permanent Waves." In the song, Lee sings of "wheels within wheels in a spiral array/A pattern so grand and complex," to describe a tide pool, then progresses on to "a quantum leap forward/In time and in space," as he sings about the expansion of the universe.

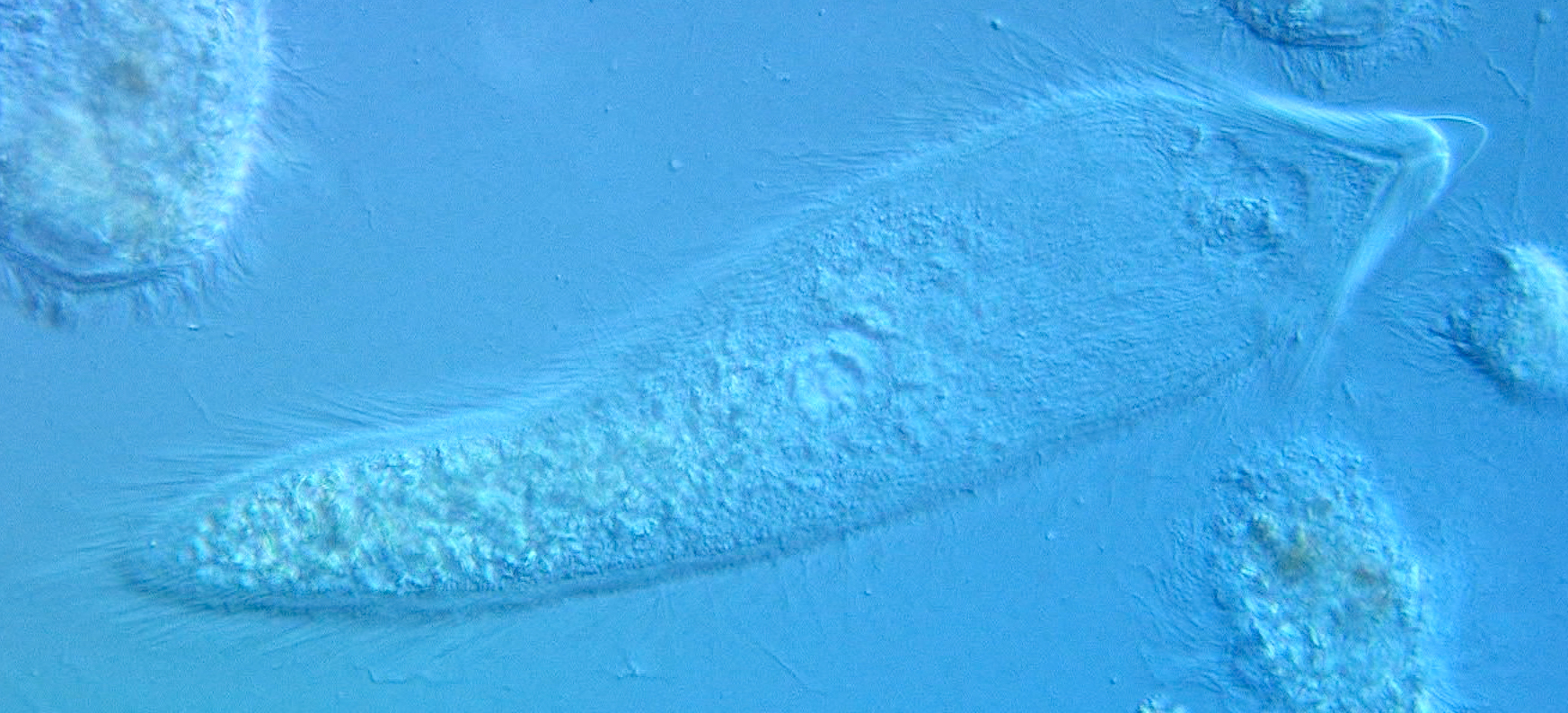

Rush is equally famed for its complex musical rhythms, and the microbe named for iconic drummer Peart also keeps a different beat from its fellows. Inside P. pearti cells, researchers discovered a unique and peculiar spinning structure, which they dubbed a "rotatosome."

Peart frequently achieves his distinctive percussive sound with a type of drum called a rototom, which has no shell and is tuned through rotation. But the function of the rotating structures inside P. pearti is still unknown, though the researchers hope that further analysis will eventually reveal its purpose, they wrote in the study.

"Many questions remain about the function and the form of the rotatosome that will hopefully be resolved in the fullness of time," the study authors wrote in their paper, which was published online Nov. 27 in the journal Nature: Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.