Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain (photos)

Julius Caesar wrote about leading two Roman invasions of Britain, in 55 B.C. and 54 B.C., in his Commentaries on the Gallic War, which can still be read today.

To the Romans of the first century B.C., Britain was a semi-mythical land beyond the seas, populated by barbarous, war-like tribespeople known as the Pretani or Britons.

Thanks to Caesar's book, the invasions have been described as the first recorded events in the entire history of the British Isles.

But until the Roman landing place in 54 B.C. was identified near a beach in the southeast of England, there was no archaeological evidence for Caesar's invasions.

Military remains

In 2016 and 2017, archaeologists from the University of Leicester in the UK excavated parts of a Roman military fort dating from the first century B.C., near the village of Ebbsfleet along the shore of Pegwell Bay, on the Isle of Thanet at the north-east tip of the county of Kent.

A defensive ditch from the fort was first discovered in 2010, by archaeologists who excavated the area as part of local government requirements before a new road was built there.

The remains of Roman weapons found at the site and clues about the local landscape in Caesar's Commentaries show the fort was built by the Romans to keep watch over the hundreds of ships of their invasion fleet at anchor in Pegwell Bay, the researchers say.

Romans in the UK

In his Commentaries, Caesar – at that time the Roman general in command of the province of Gaul, in modern France and Belgium – described leading two invasions of Britain.

In the first, which historians date to 55 B.C., Caesar invaded with two legions of infantry and fought the British for 10 weeks in the eastern parts of Kent, before retiring his troops to Gaul for the winter.

IN 54 BC, Caesar invaded again, with time with 5 legions of Roman infantry and 2000 cavalrymen – more than 20,000 men in total – near the Roman fort discovered by archaeologists at Ebbsfleet.

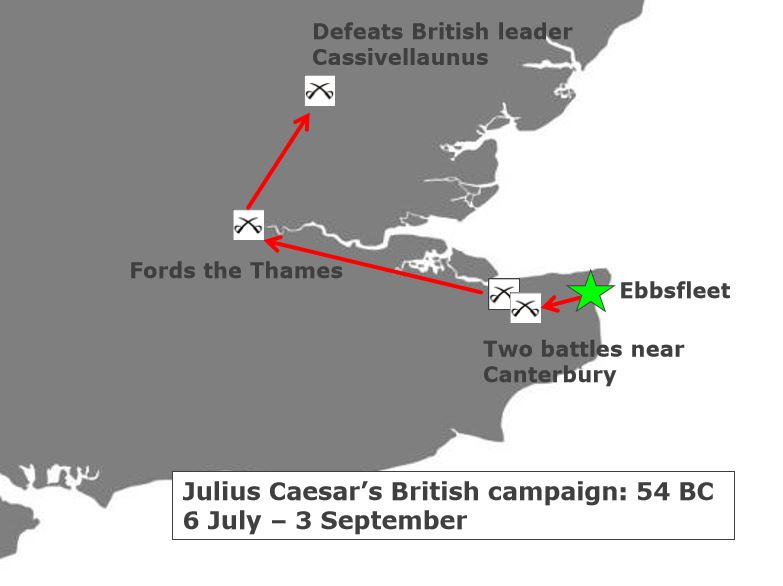

In the months that followed, the Roman armies waged war through Kent and across the River Thames into the modern counties of Essex and Hertfordshire, where Caesar forced the surrender of the British war leader, Cassivellaunus.

After imposing peace treaties on the defeated southeast British tribes, Caesar returned with his troops in September 54 B.C. to Gaul, where a poor harvest had caused unrest.

Changes in the coastline

Although the Roman fort at Ebbsfleet now lies some distance from the modern coastline, in the first century B.C. it stood on the shore of a wide channel, where it was placed to keep watch over the Roman ships at anchor in Pegwell Bay.

Caesar described leading a fleet of more than 800 ships carrying more than 20,000 Roman soldiers for his second invasion of Britain in 54 B.C.

He claimed there were so many ships that the British warriors gathered to oppose the Roman invasion took fright, and fled to hide in an area of higher ground near the landing site – probably the cliffs near Ramsgate that can be seen on the upper left of this image, say the researchers.

Positioned for security

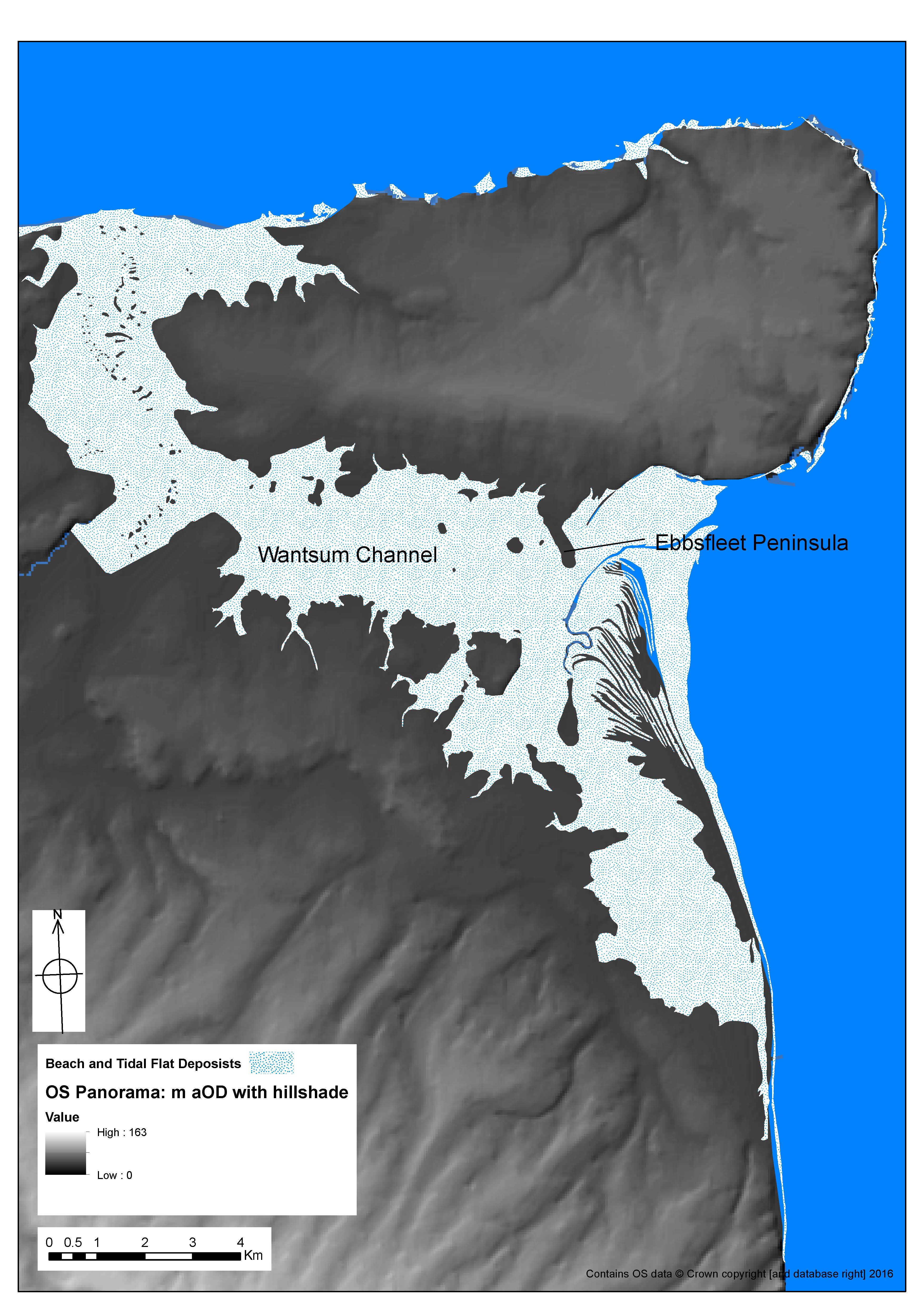

The Isle of Thanet is now part of the mainland of Kent, but in the time of Caesar's invasions it was separated by an arm of water later known as the Wantsum Channel.

The channel was filled in by land reclamation and a natural process of silting up in the Middle Ages.

The archaeological team from the University of Leicester studied LIDAR surveys of the terrain of the Isle of Thanet to learn how the shore of the Wantsum Channel would have looked in the first century B.C.

They discovered the fort at Ebbsfleet was situated on a peninsula of land jutting out from the south side of the island, placed where a garrison could keep watch of the ships of the Roman invasion fleet at anchor in the tidal waters of Pegwell Bay.

Excavated fort

Archeologists from the University of Leicester excavated parts of the Roman fort at Ebbsfleet in 2016 and 2017.

They found that the defensive ditch around the fort was built in the same way as Roman military forts known to have been built by Caesar's troops in France and Germany within a few years of 54 B.C.

They also found the remains of people who appeared to have been killed in conflict, local pottery fragments that date the ditch to the first century B.C., and pieces of iron weapons.

Important specimen

One of the most important finds is this iron spearhead, which was the business end of a distinctive Roman javelin called a pilum.

The find matches pila found in the parts of southern Gaul where Caesar recruited the troops for his legions, and in Germany where they fought.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ships of war

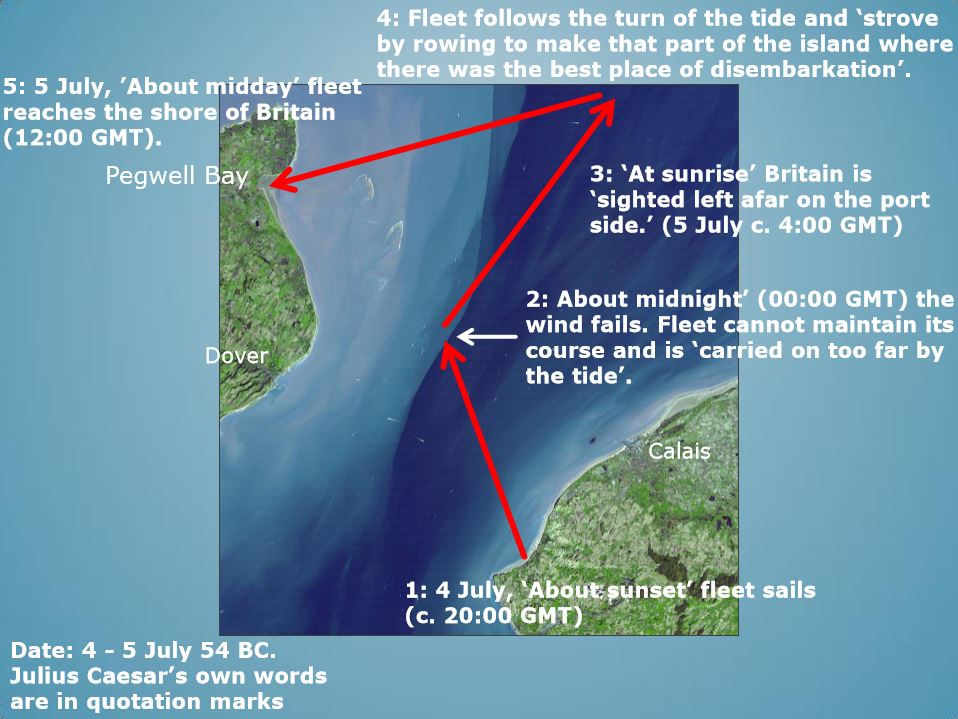

Caesar writes in his Commentaries that his invasion fleet of more than 800 ships sailed from Gaul to Britain at night, so that his soldiers could disembark in daylight, ready for battle.

This model of a Roman galley shows the type of warship used in the invasion fleet. It is based on a graffito found at Alba Fucens in Italy.

Lost in the dark

The researchers think the Roman invasion fleet of 54 B.C. embarked on the coast near Wissant, south of Calais and in sight across the channel of the cliffs at Dover in Britain.

But according to Caesar, whose words are shown in this map, the Roman fleet lost its way in the darkness when the wind fell and the tide in the English Channel carried them too far north.

At sunrise, Caesar says, the Roman spotted land "afar left" – behind them, and to port. The archaeologists think this land described by Caesar was the high cliff around Ramsgate at the northern end of Pegwell Bay.

Changes to come

The researchers say that Caesar's invasion of Britain set the course for the eventual Romanization of Britain in the decades to come, and led to the permanent Roman occupation of Britain under the Emperor Claudius after A.D. 43.

The peace treaties imposed on the tribes of southeast of Britain established the tribal rulers as "client kings" who earned power and prestige from their alliances with Rome, the researchers say.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.