Is your DNA privacy at risk?

As genetic tests become more popular, your DNA privacy is more important than ever

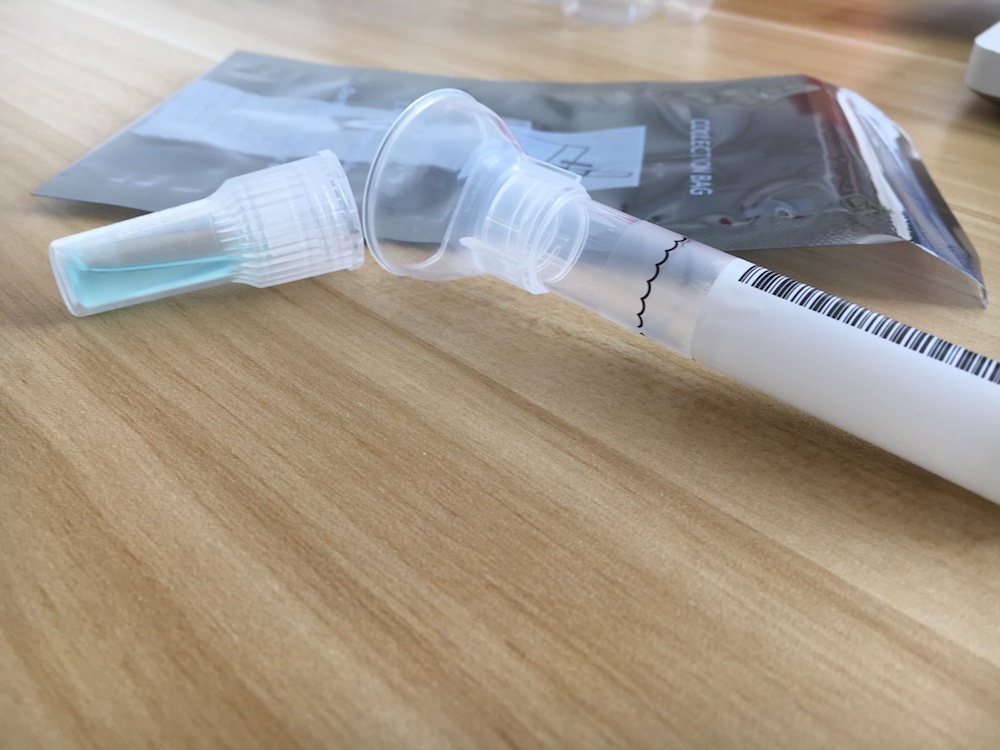

With genetic testing kits becoming more easily available, DNA privacy is increasingly a concern for many. Companies such as 23andMe, AncestryDNA and MyHeritageDNA, promise consumers the opportunity to find out more about their ancestry and genetic health risks with a simple cheek swab and mail-in kit. However, the security and privacy of the resulting gene sequences is not always clear, and there are few laws regulating companies' behavior.

Some genetic testing firms sell the results of their tests to pharmacological companies and third-party laboratories, said Peter Pitts, the president of the Center for Medicine in the Public Interest. The data is stripped of names or other identifying information, but truly anonymizing DNA is a herculean task — researchers have found that comparing anonymous DNA databases with public records could reveal the names and addresses of the people behind the gene sequences, Pitts said.

Related: How to protect your DNA data

Some of this information sharing can have benefits, Pitts told Live Science, such as the development of personalized medicine. But with few safeguards, the pitfalls are looming.

"It all leads to good places for a patient if it's used appropriately, but when there's opportunity for misuse or for monetary gain, criminals are very fast on the uptake," he said. [Understanding the 10 Most Destructive Human Behaviors]

Anonymous and aggregated?

At-home genetic testing companies have varying privacy policies. Typically, these policies require consent by customers to share personally identifiable data, but often allow the sale or sharing of anonymized DNA information, which has been stripped of names or other identifying information, or aggregate DNA information, which includes statistics like the percent of an ethnic group tested that has a particular disease risk.

Both types of information-sharing can be fraught, said Art Caplan, a bioethicist at the New York University School of Medicine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: DNA paternity tests: how they work and how to do one

Anonymized DNA is not necessarily so anonymous, given that genes are, in essence, the most identifying information of all. A 2013 study published in the journal Science used two public genealogy databases and found that researchers could correctly uncover people's surnames from their genetic data alone between 12 and 18 percent of the time. If the researchers knew the customer's surname as well as their year of birth and state of residency, they could comb the databases and narrow down the possible number of genetic profiles that might be theirs to as few as a dozen.

Revealing one target's identity in these genealogical databases also pinpointed their genetic relatives, another problem with genetic data: Your gene sequences are not yours alone. Exposure of one person's genetic information could potentially expose information about shared familial risks, Caplan said. [7 Diseases You Can Learn About from a Genetic Test]

"It could also start to impact your ethnic group," he told Live Science.

The honor system

While some of these issues are inherent in the complexities of genetic testing, others arise simply because there are not many rules constraining how at-home genetics testing companies work. Companies generally promise to keep data secure in their privacy statements, but when they sell information to third parties, Pitts said, there is no way for consumers to know who those third parties are or what their level of security might be. Similarly, Caplan said, if a company itself is sold, its privacy policies can be completely revamped.

"There's no binding thing that says when I send my DNA to 23andMe or agreed to give it to Columbia Medical School, well, forever it's anonymized," he said.

The consequences of genetic information getting into the wrong hands could be dire, both Caplan and Pitts said. There is a law, the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA), that aims to prevent insurance companies from denying coverage to healthy people based on genetic predispositions and to prevent employers from using genetic information to make decisions about hiring, firing or promotions.

However, there are loopholes in GINA, Caplan said. It doesn't apply to companies with fewer than 15 employees, or to schools. Nor does it apply to life or disability insurance. A recent bill introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives, House Bill 1313, would reverse some of GINA's protections in the workplace by allowing workplace wellness programs to restrict rewards to employees who refused to provide genetic data.

"If we don't like racial profiling in the airport, we're going to hate genetic profiling in the workplace," Pitts said.

Specific rules that could help, Pitts said, include stiff penalties, even jail time, for the hacking or theft of genetic information. Stiff penalties should also be enacted for anyone who tries to submit a DNA test without the person's consent, Caplan said. Meanwhile, the conditions consumers agree to when giving up their data should be guaranteed in perpetuity, even if the data or company changes hands, he said.

Genetic information isn't going anywhere, Pitts said, so it's time for the law to catch up with the technology. "It simply means thoughtful regulation and thoughtful consumer education," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.