The Freaky Secret Hiding Inside a Scallop's 200 Glittering Eyes

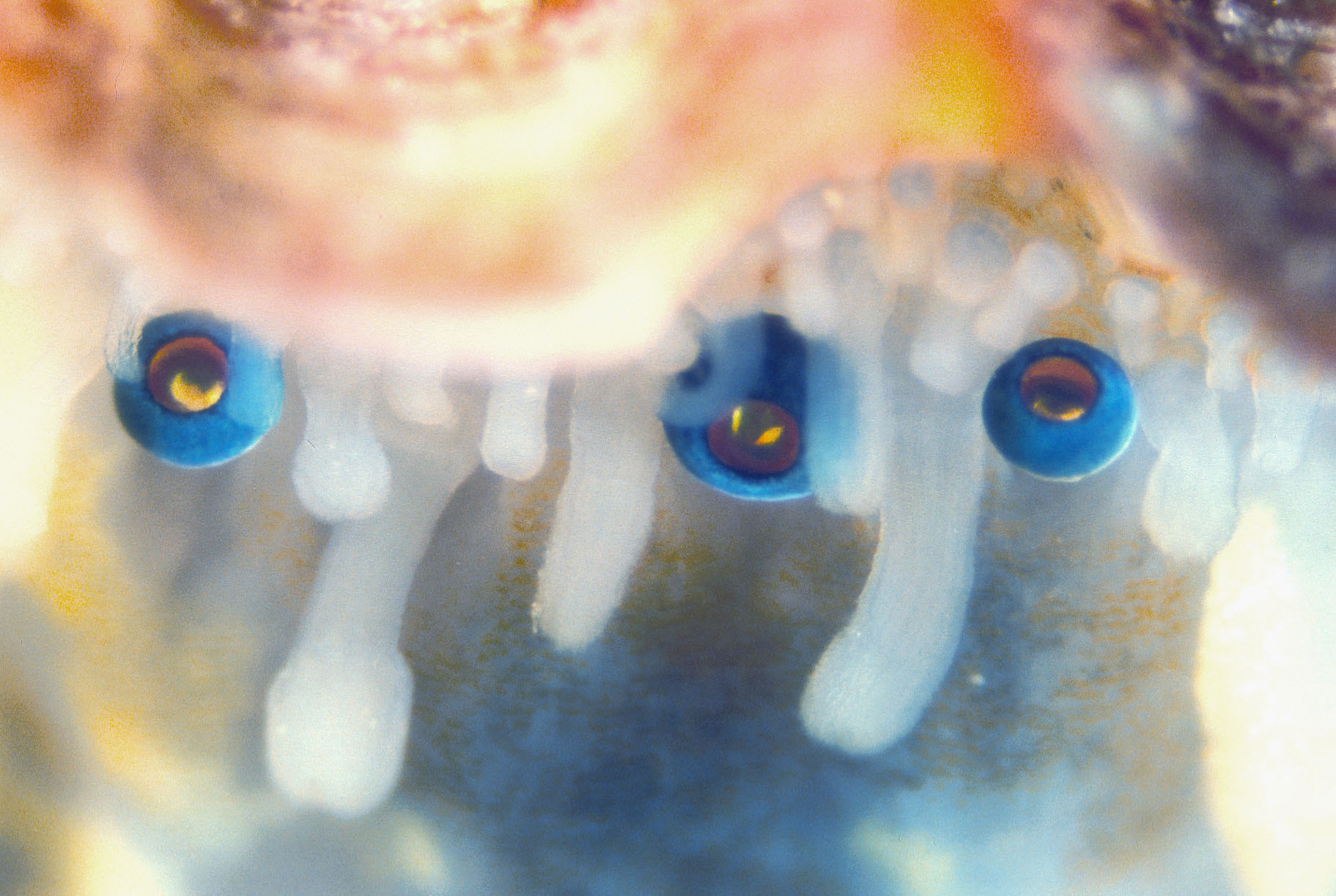

Gaze into the fleshy maw of the scallop, and lo, the scallop will gaze back — its up to 200 eyes glittering and alien, giving no sign as to what they think of you in their endless hunt for particles of floating food.

Scientists have known since at least the 1960s that scallops use mirrors at the backs of their eyes to reflect light forward and project images onto their double retinas. That was the work of Michael Land, a pioneer in researching animal vision. But Land could never figure out what those mirrors were made of, or how they worked; he guessed that crystalline guanine was involved, but all the microscopic techniques of the era dehydrated the mirrored tissue, destroying his samples before he could study them.

Now, in a paper published Dec. 1 in the journal Science, a team of researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel and Lund University in Sweden announce that they have cracked the case.

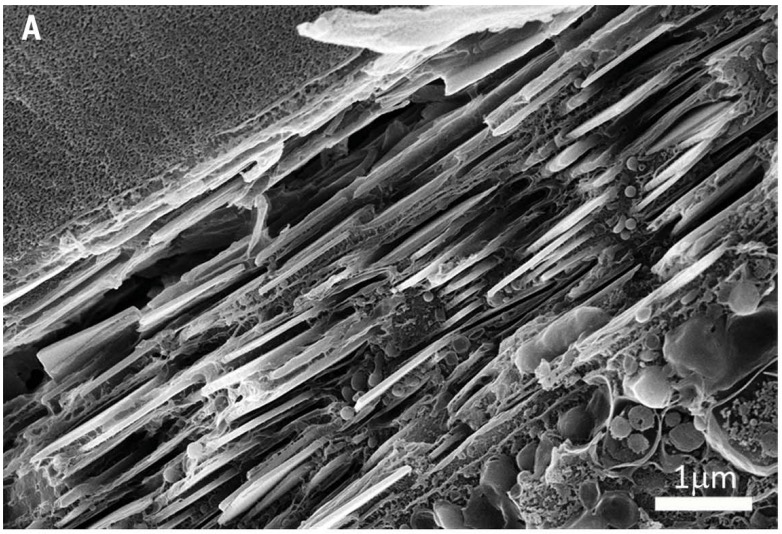

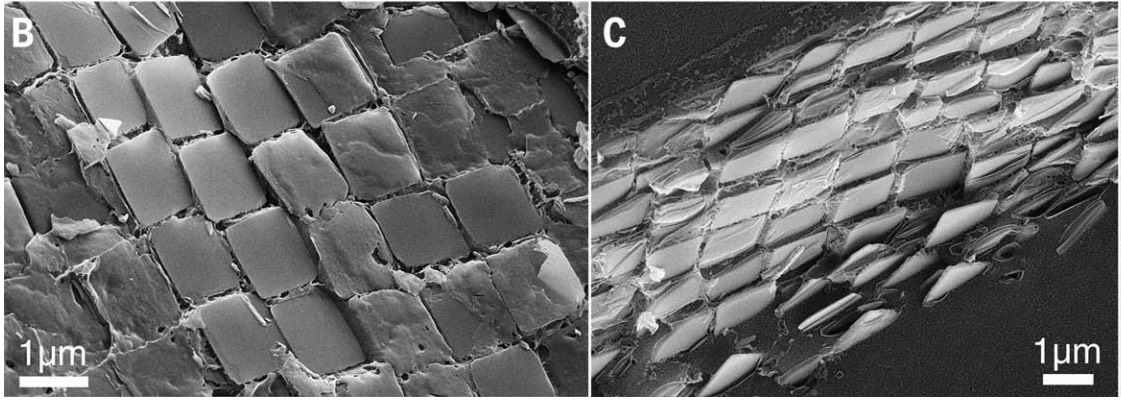

The scientists flash-froze the mirror tissue while studying it under a scanning electron microscope (this technique has the very cool name "cryogenic scanning electron microscopy" or "cryo-SEM"). They found that the mirror tissue indeed is made up of guanine crystals. But there was something strange and powerful about them. [Take our Vision Quiz: What Can Animals See?]

Guanine isn't all that rare in nature. It also turns up in certain white spiders, the skin of chameleons and some tiny, iridescent crustaceans, scientists have found.

But usually when guanine crystals form, they form as prisms — not a great shape for precisely reflecting light onto a lens. And in scallops, that precision is important; the lenses in their eyes barely refract light at all, nowhere near precise enough to focus an image.

The mirrors themselves do the focusing for scallops, and they pull that off by precisely structuring and shaping the guanine within living tissue, the researchers found.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each individual crystal of guanine is shaped into a tiny square, not a prism. The squares lay flat, bunched together in curving, concave layers without any gaps between them — their flat, shiny fronts are aimed squarely at the critter's retinas.

Imagine a bunch of chessboards shaped like satellite dishes stacked one on top of the other. The researchers compare the structure of these bunched crystals to the curving tiles of reflecting telescopes — and it turns out to be a powerful focusing mechanism, allowing each eye to train its attention on a different part of space.

Just how do scallops control the formation of crystal so finely? The researchers still don't know.

Originally published on Live Science.