Jesus' Secret Revelations? Copy of Forbidden Teachings Found in Egypt

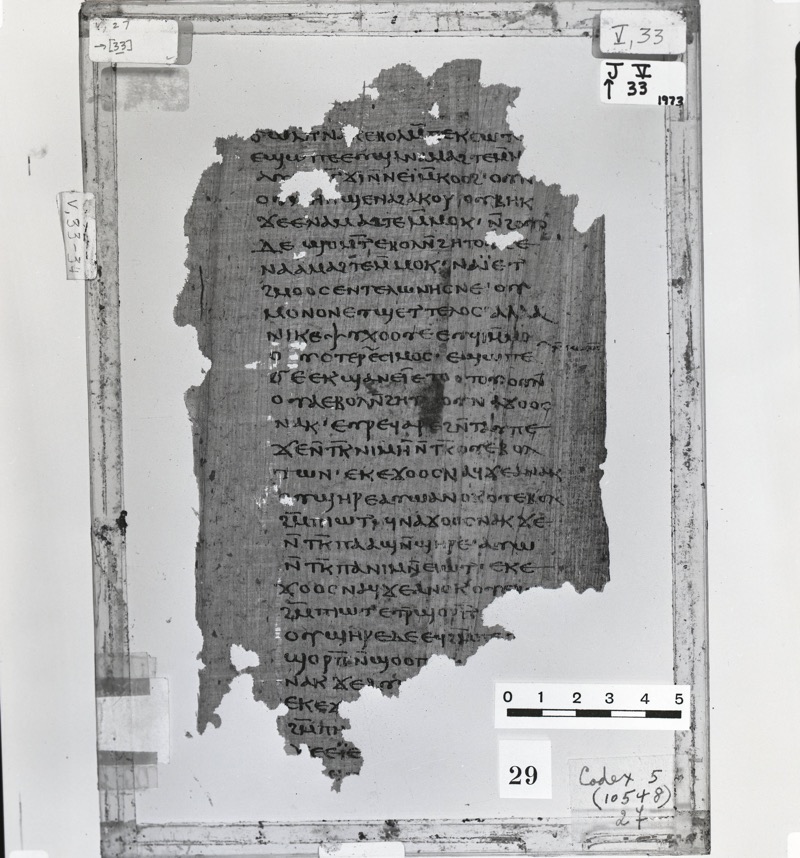

The oldest known copy of a text claiming to be Jesus' teachings to his brother James has been discovered in an ancient Egyptian trash dump, scattered among piles of fifth-century papyrus, ancient tax receipts and bills of sale for wagons and donkeys.

The manuscript is a rare, Greek-language edition of an apocryphal New Testament story called The First Apocalypse of James, that, until now, was thought to only be preserved in the Coptic language (an indigenous Egyptian language evolved from hieroglyphics), according to a statement. The text was likely written in the fifth or sixth century, said Brent Landau, a religious studies lecturer at the University of Texas at Austin, who presented the findings along with Geoffrey Smith, a religious studies scholar at UT Austin, at the Society of Biblical Literature Annual Meeting in Boston in November. The findings have not yet been subject to peer review.

The find belongs to a collection of more than 200,000 papyrus documents housed at Oxford University in England, first excavated from a rubbish heap in the Egyptian town of Oxyrhynchus in the late 19th century. Smith and Landau pieced together the document from six different papyrus fragments in the collection earlier this summer. The two had been studying the Oxyrhynchusfindings for more than two years. [Religious Mysteries: 8 Alleged Relics of Jesus]

A rare find

The manuscript is significant for a few reasons, Landau said.

For one, he said, it's written in Greek.

"Greek was the earliest language that the original Christian writings were composed in because it was sort of the universal language of the Roman empire at that time," Landau told Live Science. "It's extremely rare to find [apocryphal texts] in Greek — it was definitely the original language."

That means while this is not the first copy of the First Apocalypse of James ever found, it is likely the oldest. The only other known version of the text was discovered in the Nag Hammadi library — a collection of 13 Coptic Gnostic books excavated in Egypt in 1945. Buried in jars underground, the Nag Hammadi books were likely hidden for safekeeping sometime after A.D. 367 when Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria, defined the canon of 27 books known today as the New Testament. All other stories, like those found in the Nag Hammadi collection, were deemed heretical. [Who Was Jesus, the Man?]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Considering the manuscript's forbidden status, another surprising aspect is that it appears to be a teaching edition.

"Nearly all of the syllables are divided with these little mid-dots — little dots right in the middle of the line," Landau said.

Manuscripts of the time were often written in a fluid, continuous script. To see syllables so clearly divided like this suggests that the book was a teacher's tool produced to help students learn how to read and write in Greek.

"By the time this text would have been used in somebody's school in the fifth or sixth century, this text was effectively banned," Landau said. "So clearly, this instructor, whoever he or she was, was quite fond of The First Apocalypse of James."

Forbidden text

Gnostic texts like The First Apocalypse of James were likely banned because of their "different understanding" of what Jesus' importance was, Landau said.

"They understood Jesus much more in terms of being a revealer of human wisdom than as a messiah," Landau said. "According to these Gnostic texts, Jesus taught people that the material world was actually a prison crated by an evil god — a lot like the movie 'The Matrix,' essentially."

In The First Apocalypse of James, Jesus describes this prison to his brother. He reveals that the world is guarded by demonic figures called archons, who are blocking the path between the material world and the afterlife. "What James needs to get by them when he dies are passwords — sort of like cheat codes in a video game," Landau said.

"You can see how this is pretty counter-cultural."

Landau and Smith are currently working to publish their findings in an upcoming series of the "Oxyrhynchus Papyri," an ongoing catalog of the Oxyrhynchus discovery first published 120 years ago.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.