$450 Million Da Vinci: Why Was Damaged Painting So Expensive?

Leila Amineddoleh is the founder and managing partner of Amineddoleh & Associates, LLP in New York City, where she specializes in art, cultural heritage and intellectual property law. Amineddoleh contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Last month, I was lucky enough to enjoy a private viewing of Leonardo da Vinci's "Salvator Mundi." It was a remarkable experience, not due to the painting’s aesthetic, but because of its fame. As a lover of da Vinci, I am mystified by his genius. Art historians rejoice at new da Vinci findings, and art collectors wish to own something by the man who epitomized the Renaissance. The sale of “Salvator Mundi” ("Savior of the World") was the talk of the art world, but the sales price left many people stunned. How could a painting, a single panel, sell for $450.3 million?

This exorbitant price raises the question: What exactly did the buyer purchase? It's challenging to say the buyer procured a piece depicting da Vinci's genius. That's because da Vinci's masterpiece accumulated damage over the years, prompting art conservators to heavily repair and, in effect, change and diminish its brilliance. [Leonardo Da Vinci's 10 Best Ideas]

Rather, it's likely that the buyer acquired “Salvator Mundi” as a type of trophy — a painting that is famous simply because it is linked to da Vinci, not because of its inherent, religious or artistic value.

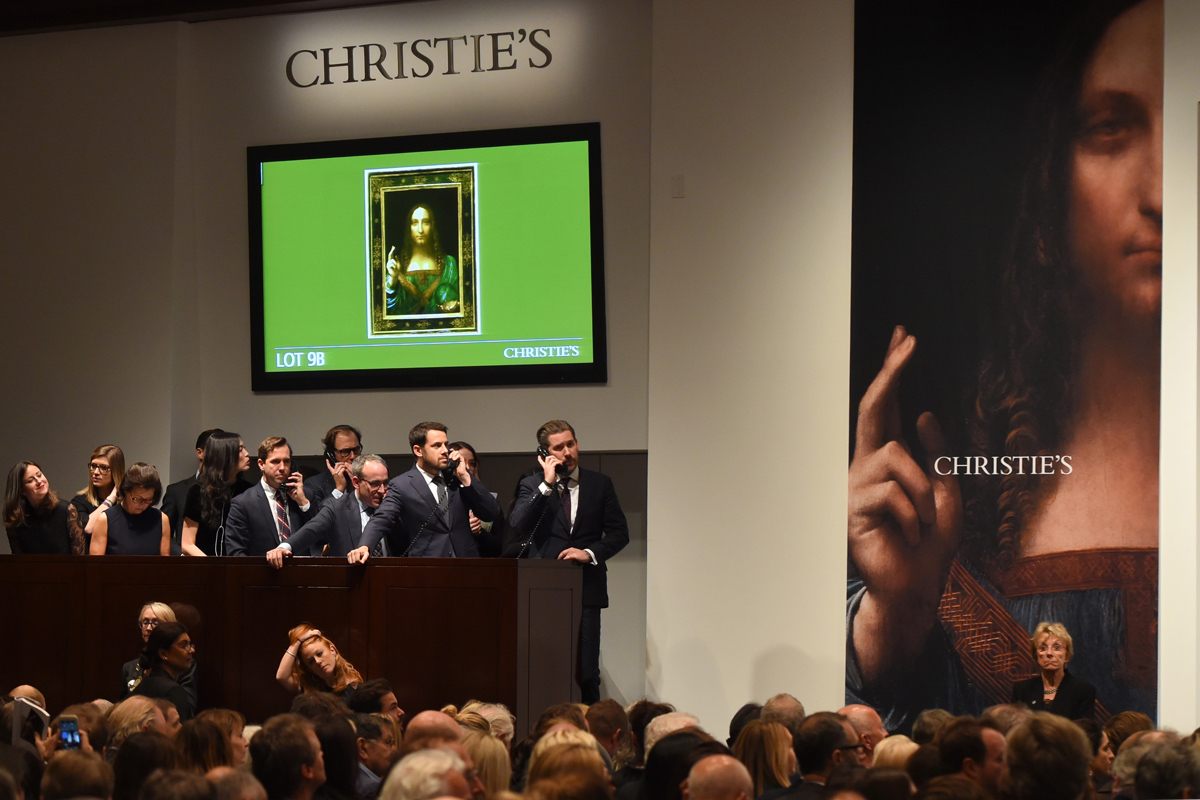

Record-breaking auction

With a $100 million bid from a third-party guarantor secured by Christie's, most art market experts predicted a record-breaking sale for over $200 million. The previous highest price paid at auction for a painting was $179.4 million for Picasso’s “Les Femmes d’Alger,” and the da Vinci sold for more than twice that amount. The astronomical price signals many things about the art market. For one, Old Masters are in vogue. Records are no longer broken only by modern artists like Cezanne, Modigliani, Munch and Picasso. As in the days of famed dealer Joseph Duveen and his connoisseur colleague, Bernard Berenson, Old Masters now command record-breaking prices again.

As with Duveen’s sales, “Salvator Mundi” was heavily marketed — Christie’s hired the advertising company Droga5 to run the campaign. The painting is religious, an image of Christ. Yet it was referred to as “the male ‘Mona Lisa,’” cashing in on the famed portrait's iconic and one-of-a-kind ubiquity and value (the "Mona Lisa" is the best known and most valuable piece of art on the planet). The campaign featured international press releases, videos (one included celebrities, like another famed Leonardo, Mr. DiCaprio), and the claim that this is the last work by the Renaissance master in private hands, referring to the panel as “The Last da Vinci.”

In fact, that is not true. The “Madonna of the Yarnwinder” is in the Buccleuch Art Collection, an impressive private collection in the United Kingdom. Yet “Salvator Mundi” became known as the only da Vinci painting privately owned. Nonetheless, the artist's limited number of works (there are few than 20 surviving paintings by him) make all of them extraordinarily valuable.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Christie’s also wisely decided to sell the Renaissance work during the postwar and contemporary evening auction, a sale known to attract major collectors and celebrity buyers. The auction house explained its unusual placement with the statement, "Despite being created approximately 500 years ago, the work of Leonardo is just as influential to the art that is being created today as it was in the 15th and 16th centuries. We felt that offering this painting within the context of our Post-War and Contemporary evening sale is a testament to the enduring relevance of this picture."Humorously, one critic quipped that it was sold with postwar items because 80 percent of the work was recently painted, during conservation. [11 Hidden Secrets in Famous Works of Art]

Lengthy provenance

Does the history of the panel really stretch back to over 500 years ago? Its provenance is fascinating and linked to royalty. It is believed to have been commissioned around 1500 for Louis XII of France and his consort, and it eventually made its way into the possession of Charles I of England in 1625. The painting purportedly exchanged hands many times with members of royal households until the mid-18th century. The work then disappeared for a number of years. It was eventually purchased in 1900 (after heavy over-painting), after which time it made its way to Wales where it miraculously survived a bombing during World War II. It was stored in a house that was bombed, yet it survived by sheer luck. The painting finally sold at auction in 1958 in Louisiana for about $90.

The value rose dramatically this century. It was sold at an estate sale in 2005 for $10,000 to an art consortium. The group hired Dianne Dwyer Modestini, a conservator at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, to restore the painting. After extensive work, it appeared in a 2011 exhibition at the National Gallery in London, identified as a newly rediscovered da Vinci. With the museum’s attribution endorsement, the painting was sold to Swiss businessman Yves Bouvier. But now the price was much higher — 8,000 times higher, selling for $80 million. The Swiss art adviser flipped the work for $127.5 million. The buyer, famed Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev,consigned it to Christie’s in what turned out to be the decade'sblockbuster sale.

Genuine Leo?

When the consortium purchased the work in 2005 it was so heavily over-painted that it was hard to recognize it as a da Vinci. It was also damaged and in desperate need of restoration, believed to be a copy of an original da Vinci work by the master’s pupil, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. Since the consortium’s purchase in 2005, numerous experts supported its attribution and it became generally accepted as a da Vinci. Art connoisseurs like Martin Kemp, an emeritus professor of art history at University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom, and one of the leading da Vinci experts, believe it has a “presence” like other da Vinci works. On the other hand, critics point to its murky provenance, imperfect orb (reflecting a lack of understanding about optics), and general flatness to discredit the da Vinci attribution.

For connoisseurs supporting the da Vinci attribution, what exactly are they endorsing? The majority of what is seen is not by da Vinci because the work was extensively restored. With only a small fraction of the remaining work actually done by the master, why is it still attributed to him? It begs the question: What is authorship? When does a painting cease to be the “original” work by the artist? [11 Hidden Secrets in Famous Works of Art]

As an art lawyer, I work on matters related to authentication and forgery. In one case, one of my clients had purchased a work altered by a prior owner. Somewhere in the work’s history, someone had added additional images to a van Gogh preparatory work in order to increase its value. This information was discovered after the sale, but is it necessary to reveal information about modification to a potential buyer?

When valuable art is sold, the transaction is generally accompanied by a purchase and sales agreement that lists information about the work, including the identity of the artist and the condition of the object. These representations and warranties are the basis of the agreement — the identity of an artist and condition of the work are material aspects of an agreement and should be captured in a warranty. If the artwork fails to conform to the seller’s affirmations or promises, a buyer may be able to cancel, that is demand rescission of the agreement and void the sale. But the “Salvator Mundi” sale pushes the limits of authentication because it signals that heavily restored works, coming dangerously close to being copies, are sold as authentic originals for extravagantly high prices.

It is interesting to consider the term "authentic." What makes a work authentic? Does heavy restoration alter the attribution? Can a painting lose its authorship? Does attribution result merely after an artist’s hand touches a work? In that case, this $450.3 million sale is the product of the "cult of the artist." During the Renaissance, people began believing that artists injected something of themselves in their works. The cult of the artist emphasized a creator’s individual genius. Works by these cult-like figures were coveted. Anything even touched by one of these creative geniuses became valuable, in the same way that anything touched by a saint or religious figure became blessed, embodying sacred properties. These artworks became like relics — highly prized and sought-after. Is this just a plea to be connected to the artist?

“Salvator Mundi” was heavily restored. The majority of what is visible was not done by da Vinci. This became obvious when photos of the work before the restoration were circulated online. Thomas Campbell, former director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, posted an image of it on Instagramwith the caption, "450 million dollars?! Hope the buyer understands conservation issues ... @christiesinc #leonardodavinci #salvatormundi #readthesmallprint." His post was not well-received by some in the industry. Yet the market still accepted this work by da Vinci.

What does it say about the market? With the limited number of Old Masters with strong provenance, it may signal a willingness of collectors to spend vast sums on less desirable works or objects with murky pasts. It is stunning that someone would pay nearly half a billion dollars on a piece with a contested attribution. As Evan Beard, a National Art Services executive at U.S. Trust, told CNBC, "It’s a trophy, not an Old Masters’ painting." [Anatomy Meets Art: Da Vinci's Drawings]

Is that what the art market has become? If this painting is a trophy, then "Salvator Mundi" has lost its meaning. The work is no longer appreciated for its inherent, religious or artistic qualities, but for its connection to a painter whose own past is shrouded in mystery and genius. And what about the subject of the painting? What about the man in the picture? At the risk of sounding trite, what would Jesus think?

I think the staggering price is absurd. It is shocking to the conscience. The sum paid is difficult for most of the world’s population to grasp, and probably impossible to understand for communities lacking clean drinking water and access to health care, for people living in abject poverty, and for the starving masses. Many people made vast sums of money from this work, and the robust art market clearly supports and encourages these types of sales. As a lover of da Vinci, it saddens me that his name has become commoditized and marketed to sell an image of Jesus Christ that is a shadow of its original creation.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.