Here's Why the Ventura Wildfire Is So Explosive

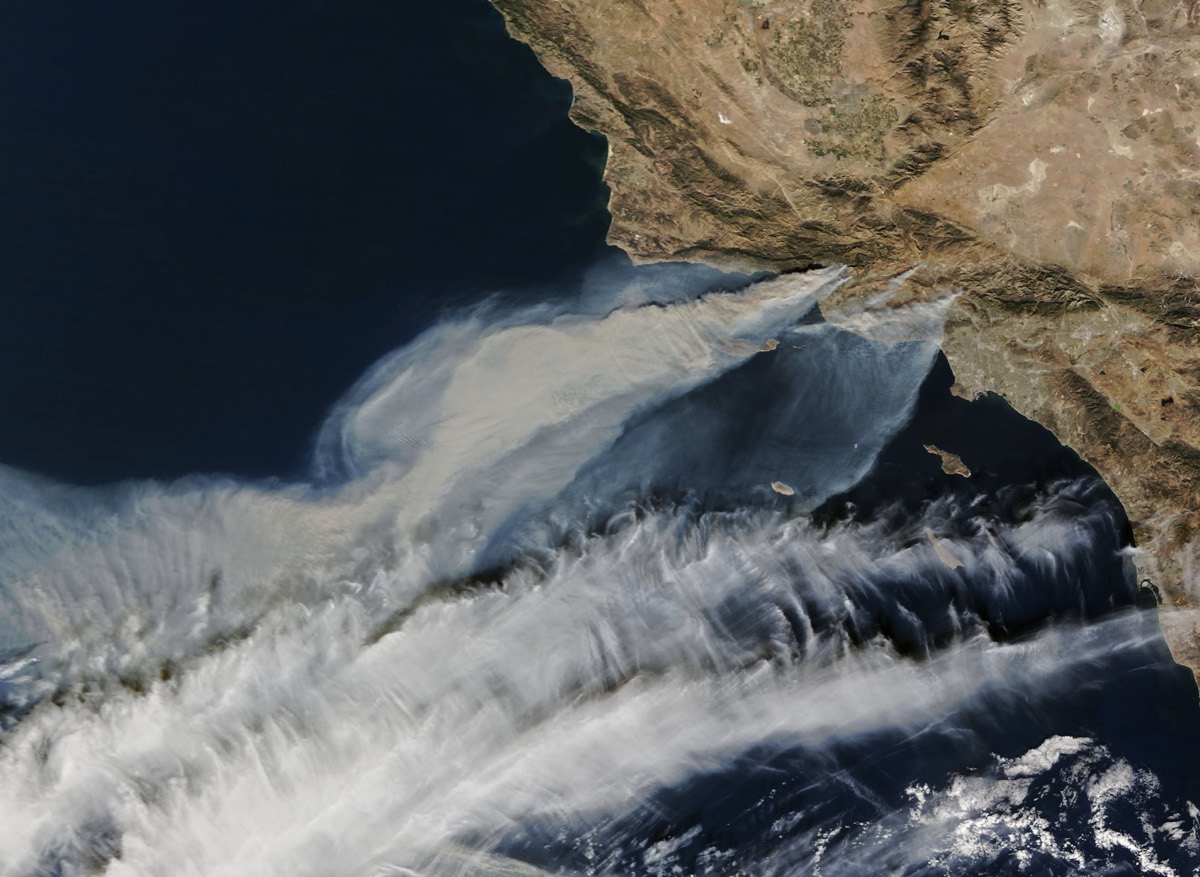

A disastrous combination of tinder-dry vegetation, the strongest Santa Ana winds in a decade and a spark caused a wildfire to explode in Ventura County, California, north of Los Angeles, overnight Monday (Dec. 4). Less than 24 hours later, the blaze had torn through more than 45,000 acres and destroyed 150 structures, with windy conditions hampering efforts to combat the flames.

While not unprecedented, such winds and wildfires are somewhat unusual this time of year, as the wet season has usually kicked in by now, quashing the potential for fires to start and spread, said Eric Boldt, the warning-coordination meteorologist for the National Weather Service in Los Angeles. But dry weather this year left conditions primed for the Thomas fire and other blazes that have broken out in the Los Angeles area.

Much is uncertain about how phenomena like the Santa Ana winds might change as the climate warms, but overall hotter, drier conditions mean that events like this one will only become more likely when they do blow down from the mountains, experts say. [Wildfires Blaze in Northern California (Photos)]

Of the five fires burning in the Los Angeles area, the Thomas fire in Ventura is by far the biggest, at 65,000 acres as of Wednesday morning, and has triggered the evacuation of 27,000 people. The Rye fire had burned some 7,000 acres and forced the closure of Interstate 5 in Santa Clarita. The Skirball Fire, at 50 acres, forced the closure of part of the 405 Freeway near the Getty Center and was threatening homes in Bel-Air.

The fires have rapidly ballooned in size, fueled by the fierce Santa Ana winds blowing down from the hills to the east of the city.

The Santa Ana winds are an example of a phenomenon more generally known as katabatic winds, when air that's under high pressure flows downslope. As it does so, it compresses and becomes warmer and drier. In Southern California, this happens when a high-pressure area sits over the Great Basin region; the air wants to flow from that area of high pressure to an area of low pressure usually found offshore, explained Norman Miller, a climatologist at the University of California, Berkeley. As it does so, the air flows through valleys that channel the winds to higher speeds.

During this week's Santa Ana event, a gust of 78 mph (126 km/h) was recorded at one outpost at an elevation of 4,000 feet (1,200 meters), Boldt said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These winds are a common feature of California autumns, and the winds, as well as the hot, dry conditions they usher in, raise the risk of wildfires. The Santa Anas tend to peak in October, Boldt said, when vegetation is also dry after the long summer dry season.

Santa Ana events can happen into the winter, but usually the wet season has kicked in by then, lowering the fire risk. This fall, though, "we've virtually had zero precipitation," Boldt told Live Science.

Temperatures have also been exceptionally warm. "Thanksgiving was 95 degrees [Fahrenheit, or 35 degrees Celsius] here," Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), said. "It's effectively summer conditions here, still." Those conditions serve to dry out vegetation even more, vegetation that was abundant thanks to ample rains last winter that fueled rapidly growing plant species, Miller said.

The fires are the latest in what has already been one of California's worst wildfire seasons on record. Blazes in Northern California in October killed at least 43 people and likely caused billions of dollars in damage, according to the reinsurance firm Aon Benfield.

The effect of a changing climate on California's fire risk is a major concern, but it's a complex question because of the myriad factors that affect wildfires. [8 Ways Global Warming Is Already Changing the World]

Work Miller has done suggests that the Santa Ana winds could become faster, hotter and drier as overall higher temperatures intensify the high-pressure systems that fuel the winds. But there is still a lot of uncertainty on how the Santa Anas might be affected, said Swain, who could see the plumes of smoke as he spoke from the UCLA campus.

More certain is that as temperatures rise, both summer and fall in California will be hotter overall, making it more likely that vegetation will be dried out and primed to fuel wildfires, he said.

So, while we can't say for sure whether intense Santa Ana events like this one will be more or less common in the future, "we know that when they occur, they're more likely to have an impact like this," Swain said.

Original article on Live Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.