Cave of the 'Mayan Underworld' Filled with Methane-Eating Creatures

In the subterranean rivers and flooded caverns of Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula — once thought to hold the path to Xibalba, the mythical Mayan underworld — scientists have uncovered a liminal world where methane is the unlikely driving force for life.

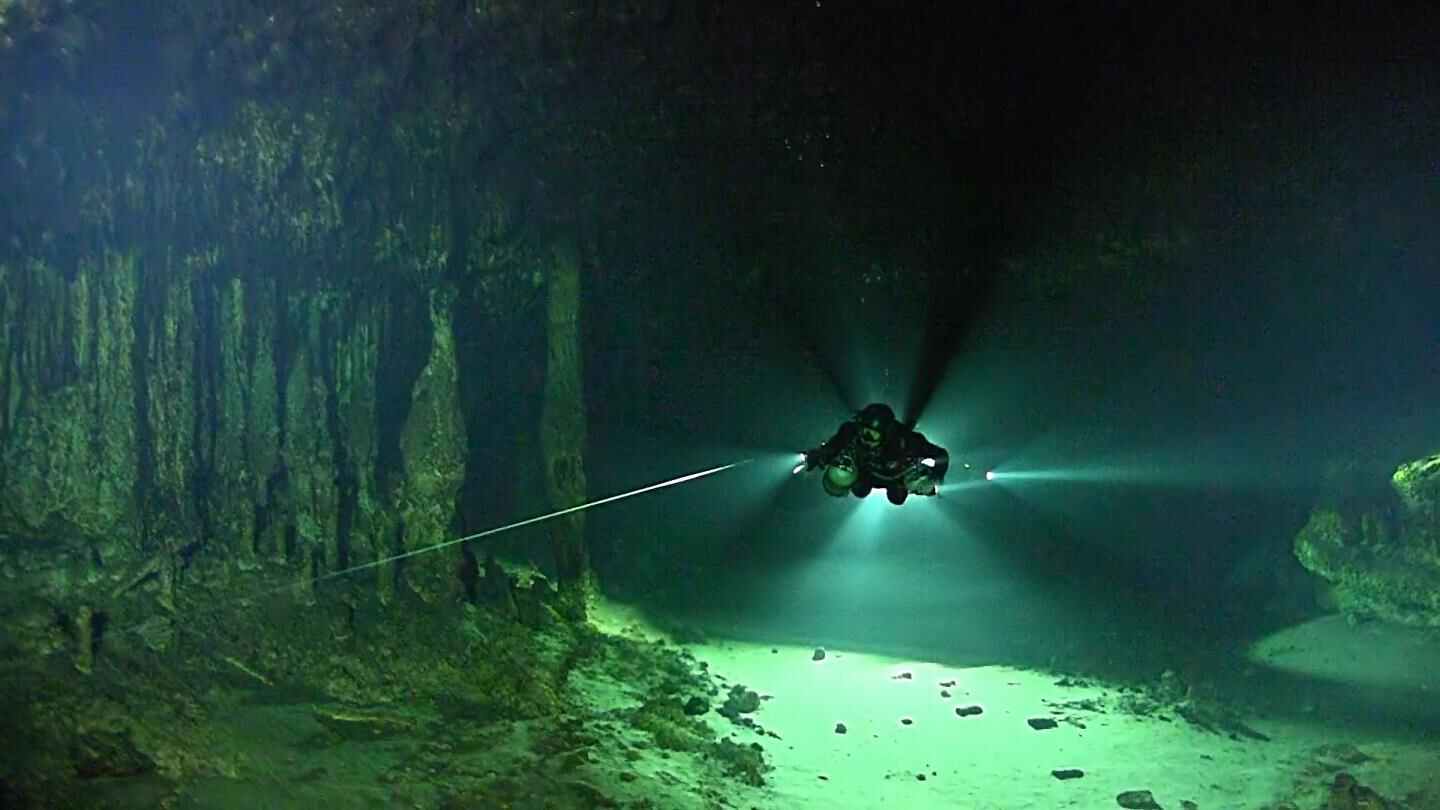

After plumbing the depths of Ox Bel Ha, a submerged estuary complex that rivals Texas' Galveston Bay in size, researchers from the U.S., Mexico, the Netherlands and Switzerland report in a new study that their expedition was the most detailed ecological study to date of a coastal cave system that is constantly underwater. The feat was so pioneering, in fact, that it necessitated the use of techniques previously employed by deep-sea submergence vehicles, they said.

The Ox Bel Ha cave network is unique because it harbors two distinct layers of water: freshwater, fed by rain falling through sinkholes — which doubled as access points for the scientists — and salt water, stemming from the ocean. [Amazing Caves: Pictures of the Earth's Innards]

In a study published on Nov. 28 in the journal Nature Communications, the team described how methane that forms beneath the jungle floor migrates downward into the watery depths, unlike soil-bound methane, which diffuses upward into the atmosphere.

Once the methane sinks into the water, bacteria and other microbes consume it — along with any dissolved organic materials carried by the inrush of fresh water.

The microbes then "set a stage" for a food web largely populated by crustaceans, including a species of shrimp that derives about 21 percent of its nutrition from methane, the scientists said.

The researchers were surprised by their findings; previous studies had suggested that cave life-forms subsisted on vegetation and other detritus that filtered into the caves from the tropical forest above.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Finding that methane and other forms of mostly invisible dissolved organic matter are the foundation of the food web in these caves explains why cave-adapted animals are able to thrive in the water column in a habitat without visible evidence of food," study lead author David Brankovits, who conducted the research during his doctoral studies at Texas A&M University at Galveston (TAMUG), said in a statement.

Because the mechanisms of the cave ecosystems mirror those found in the deepest parts of the world's oceans, these findings may help researchers understand how deoxygenation caused by the effects of carbon dioxide emissions might alter the balance of life in the so-called "oxygen minimum zones."

"Providing a model for the basic function of this globally-distributed ecosystem is an important contribution to coastal groundwater ecology," study co-author Tom Iliffe, a professor in the marine biology department at TAMUG, said in a statement.

"[It] establishes a baseline for evaluating how sea level rise, seaside touristic development and other stressors will impact the viability of these lightless, food-poor systems," Iliffe said.

Original article on Live Science.