Bizarre Origins of 4th-Century 'Santa Claus Bone' Revealed

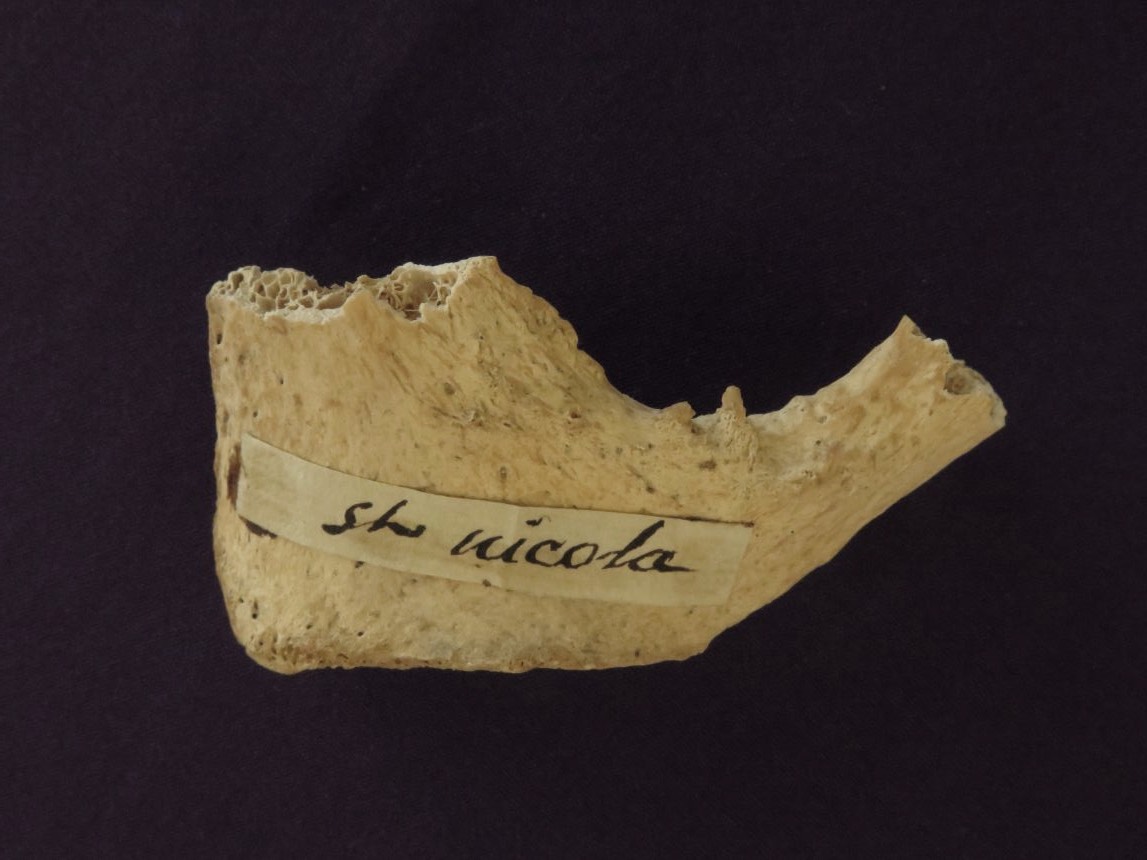

A pubic bone claimed to be that of St. Nicholas, whose generosity inspired tales of Santa Claus, has been dated to the fourth century by scientists at Oxford University. The researchers said they believe the bone may really come from the saint.

However, the bone has a bizarre backstory that calls into question whether the relic is really from St. Nicholas, Live Science has found.

The saint passed away around the year 343 in Myra, in what is now Turkey. The fourth-century date of the bone "suggests that we could possibly be looking at remains from St. Nicholas himself," Tom Higham, an archaeology professor at Oxford University, said in a statement issued by Oxford. The claim has gone viral online, with media outlets proclaiming that a bone belonging to the real "Santa Claus" may have been found. [Religious Mysteries: 8 Alleged Relics of Jesus]

Live Science found that a collector, who asked to remain anonymous, sold the bone to a shrine in Illinois that claims to have relics from over 1,500 saints. A relic can be part of the body of a saint (or someone otherwise regarded as being very holy) or an item that the individual once used.

The Catholic priest who runs the shrine said that a group of nuns from the Catholic diocese of Lyon, France, once cared for the St. Nicholas bone, among other relics, but allowed the relics to be sold on the antiquities market several years ago.

The collector has sold hundreds, possibly even thousands, of relics over the years on eBay. These include 15 relics supposedly from St. Joan of Arc and relics supposedly from many other saints: St. Peter, St. Lawrence, St. Joseph, St. Francis of Assisi, St. John the Baptist, St. Thomas Aquinas, St. Therese of Lisieux among many others.

The collector also sold on eBay numerous nails and wooden fragments that were supposedly from the cross that Jesus was crucified on and a fragment from the crown of thorns that Jesus supposedly wore when he was crucified. The sale price of the relics varied from less than $100 to more than $1,000. [Proof of Jesus Christ? 6 Pieces of Evidence Debated]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The team was unaware of much of the bone's backstory, Georges Kazan, a research fellow at Oxford who helped conduct the tests, told Live Science in an interview.

A spokesperson for the Catholic diocese of Lyon said that she is looking into the claims that the St. Nicholas bone was once owned by the diocese and that a group of nuns in the diocese allowed the bone and other relics to be sold on the antiquities market.

Bizarre backstory

St. Nicholas was born into a wealthy family around the year 270, but he donated his wealth to help the poor and needy, according to historical records. The saint also reportedly risked persecution to become a Christian (Christians were persecuted in the Roman Empire until the fourth century) and eventually became the bishop of Myra. Tales of his generosity and kindness inspired tales of a similarly generous Santa Claus. [The 10 Most Controversial Miracles]

In the 11th century, sailors from the Italian cities of Bari and Venice broke into the cathedral at Myra, stealing bones that they believed belonged to St. Nicholas. The thieves brought the relics back to Italy, where the items are interred today in churches in Bari and Venice.

However, the bone that the Oxford team tested was not from either the Bari or Venice churches, but rather was found in the Shrine of All Saints at St. Martha of Bethany Church in Morton Grove, Illinois. The bones in Venice and Bari have never been dated with radiocarbon, as this partial pubic bone was, although the Oxford team said it hopes that one day it will be allowed to perform the procedure on those relics.

The nuns who sold the bone belonged to an order called the Poor Clares, wrote Father Dennis O'Neill of St. Martha of Bethany Church, in his book "Relics in the Shrine of All Saints at St. Martha of Bethany Church in Morton Grove, Illinois" (Trafford, 2015).

"Why it [the bone] went on the market, we don't know," O'Neill told Live Science in an interview, saying that he didn't want to contact the nuns, as he believes that they do not want their identity to be revealed.

O'Neill purchased the bone from the collector as part of a lot that also included burial fabrics supposedly from St. Colette of Corbie (1381-1447) and St. John Francis Regis (1597-1640), a mandible supposedly from St. Christina (who lived during the third century) and two teeth supposedly from St. Fiacre (who died around 640), he said. O'Neill said he didn't remember how much he paid for the relics, but thought that altogether it may only have been $100 or $200.

"It's a sin to sell relics," O'Neill said, adding that "it can be a virtue to rescue them if you're rescuing them back for the church."

The collector did not reveal where he got the St. Nicholas bone; however, O'Neill said that some of the relics in the lot he purchased had letters and notes that matched the handwriting of notes attached to another relic he purchased on eBay that was attributed to the Poor Clares of Lyon.

During the French Revolution (1787-1799), the Poor Clares were "heroic" in their efforts to stop relics from being plundered and took care of them after the revolution was over, O'Neill noted.

There are several Poor Clare monasteries outside Lyon, Live Science found.

A message sent to the collector by Live Science was not returned at the time of publication.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.