Ancient Rock Art Mapped in Amazing Detail, Revealing 100-Foot Snake

This story was updated Dec. 11 at 11:40 a.m. EST.

Ancient rock art isn't always easy to reach, but a researcher in Venezuela has solved this challenge with a bit of modern technology: A camera-equipped drone that zipped across a rocky, watery landscape to photograph ancient artwork depicting people, cultural rituals and animals, a new study reports.

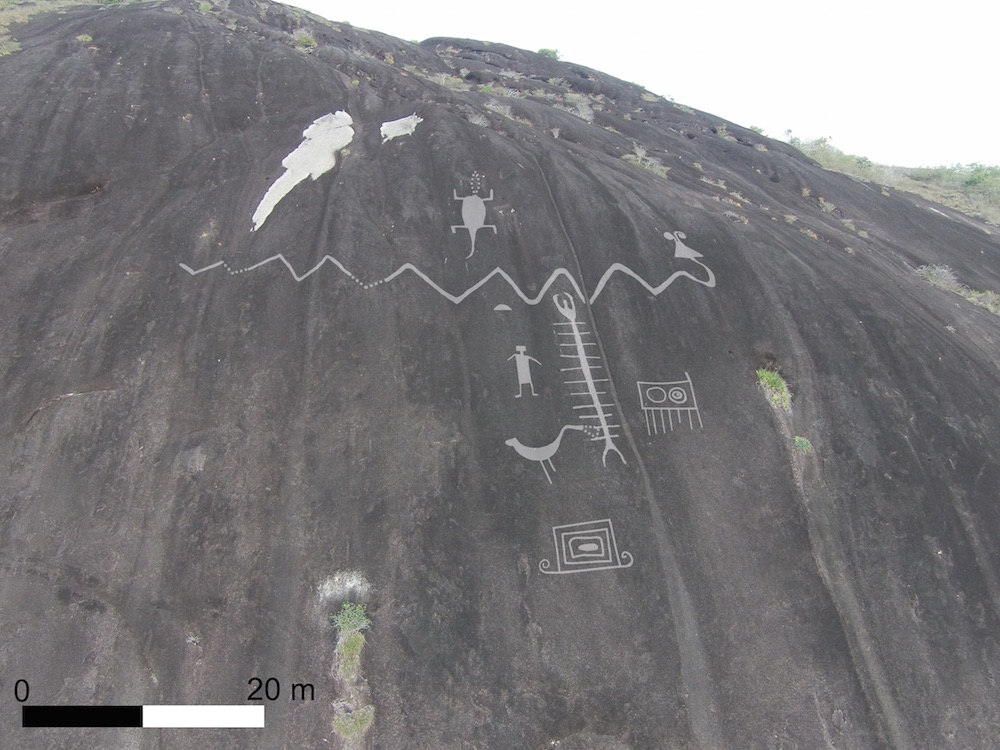

The drone-recorded engravings, in addition to more accessible rock art along the Orinoco River in western Venezuela, are some of the largest rock engravings found anywhere in the world, the researcher said. One panel is more than 3,200 square feet (304 square meters) and has 93 engravings. Another engraving portrays a 98-foot-long (30 m) horned snake.

The engravings appear to date to pre-Columbian (before 1492) and colonial times (1492 to the 19th century), said the study's author Philip Riris, an archaeologist at University College London in the United Kingdom. Some may be up to 2,000 years old, he noted. [In Photos: The World's Oldest Cave Art]

"This represents a major step towards an enhanced understanding of the role of the Orinoco River in mediating the formation of pre-conquest social networks throughout northern South America," Riris wrote in the study. (Pre-conquest refers to the time before the Norman conquest of England in 1066.)

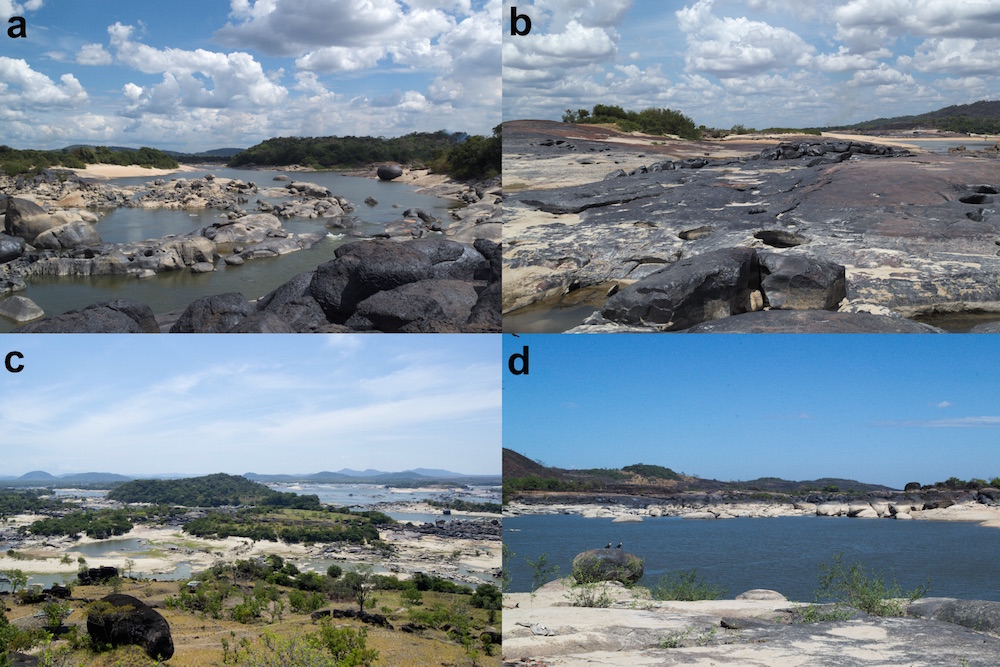

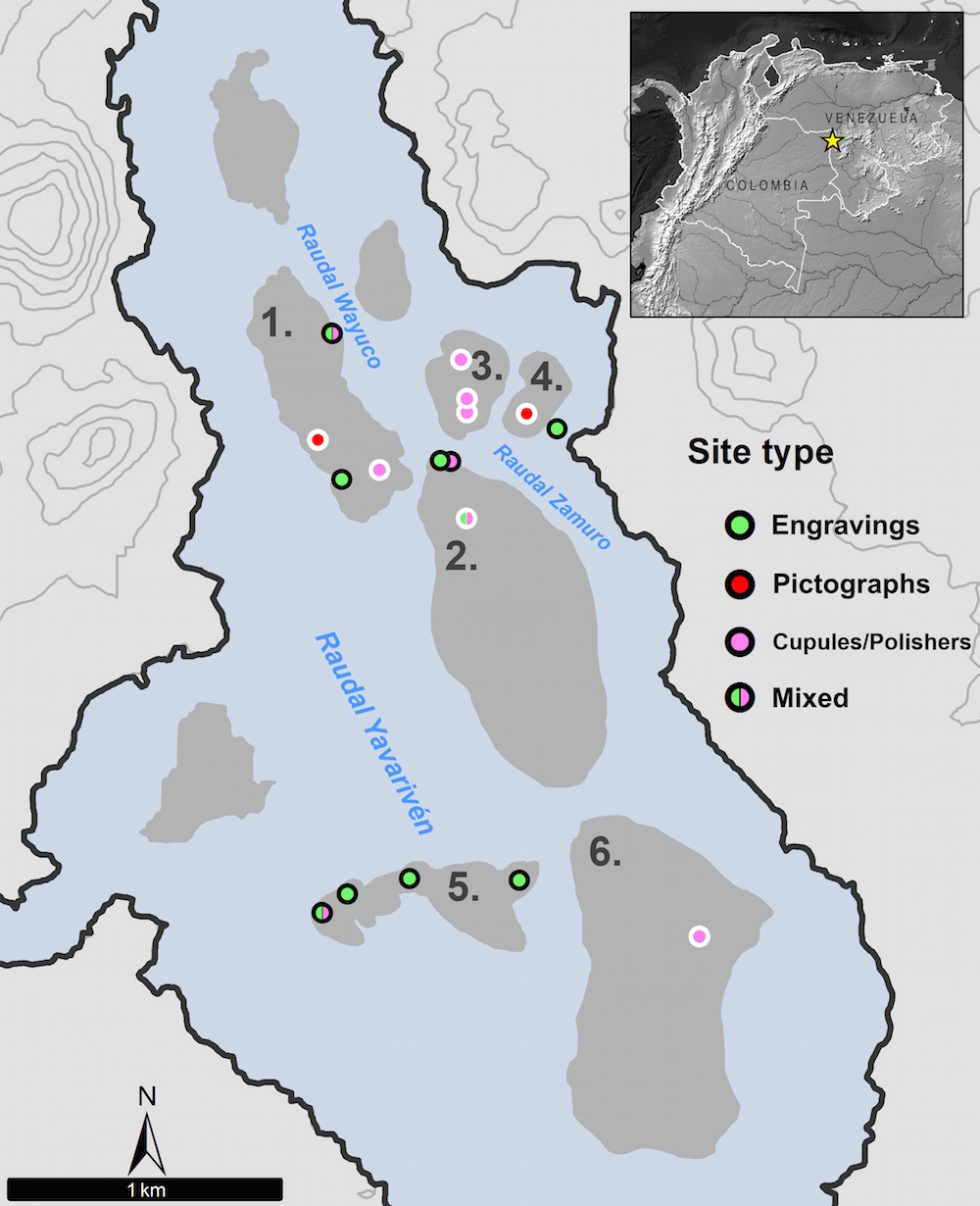

Scientists found the petroglyphs (in Greek, "petra" means "rock" and "glyph" translates to "carving") on rock faces around the Atures Rapids (Raudales de Atures), a place where the mighty Orinoco River flows through a narrow passage filled with granite boulders. Some of the petroglyphs were discovered because of historically low water levels in the Orinoco River in February 2015, Riris said.

In all, he found eight groups of petroglyphs on five islands, including on exposed bedrock outcrops within the rapids, Riris said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It's not entirely surprising that the Atures Rapids are filled with ancient petroglyphs. According to myths from the Piaroa, indigenous people who live in the middle Orinoco Basin, the rapids are seen as the birthplace of the sun and of Wahari, a mythological figure.

Some of the petroglyphs appear to illustrate myths from the various cultures of the regions. For instance, the elongated horned snake may be from a "myth describing the slaying of a monstrous serpent by the son of the creator deity and culture hero Wahari," Riris wrote in the study.

Other petroglyphs show a flute player surrounded by other human figures. This scene likely depicts an indigenous rite of renewal, he said. It's possible that this rite coincided with a seasonal emergence of the engravings during harvest time just before the wet season, when the islands were easier to reach, Riris said.

The newfound petroglyphs are similar to rock art in Brazil and Colombia, and will help researchers understand the ancient cultures of the Orinoco River and how they may have influenced cultures farther inland, Riris said.

However, petroglyph discoveries haven't always been greeted with such acclaim.

In 1691, when Jesuit missionaries visited an "oracle" in the Atures region, they saw a number of the so-called pagan petroglyphs high on a hillside.

"When our missionaries came to this place, Satan was silenced at once, and the Devil disappeared from there, the diabolical responses ceasing henceforth with the astonishment and admiration of the pagans […] whom before had treated with the demon so easily," the missionares wrote. "With this, the infidels knew the power of God, and the force and efficacy of the ministries against the powers of Hell."

In contrast to this nearly 330-year-old account, Riris said that the newfound petroglyphs will help researchers learn more about these ancient cultures. "These engravings are embedded in the everyday — how people lived and traveled in the region, the importance of aquatic resources and the seasonal rhythmic rising and falling of the water," he said in a statement. "The size of some of the individual engravings is quite extraordinary."

The study was published online Dec. 6 in the journal Antiquity.

Editor's Note: This story was updated to fix an error about the petroglyph snake's length. It is 98 feet (30 m) long, not 305 feet (93 m) long.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.