Why We Can't Stop Seeing Zigzags in This Freaky Optical Illusion

Who would win in a fight: the part of the brain that likes to see curves or the part that prefers corners?

This conflict underlies a new kind of optical illusion, dubbed the "curvature blindness illusion" in a new paper published in the November-December issue of the journal i-Perception.

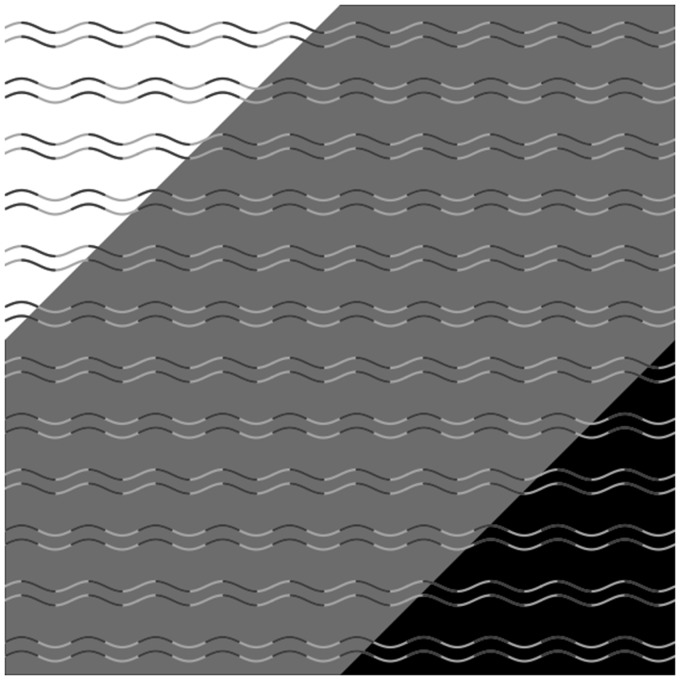

Kohske Takahashi, an associate professor of experimental psychology at Japan's Chukyo University, showed a small sample of students the image below and asked them a simple question: What do you see in the gray, middle section of this picture — curved lines, angled lines or both? [The Most Amazing Optical Illusions (And How They Work)]

If you see alternating rows of wavy and zigzagging lines (like all study participants did), you're both right and wrong. The truth is, every line in this image is an identical, wavy shape. And yet, our brains reliably see sharp-cornered zigzags stitched across the middle section of the image. The reason this illusion works so well is unclear, but Takahashi offers a few hypotheses in his paper.

For one, Takahashi writes in the paper, it seems likely from this curvature blindness illusion (as well as from previous illusion research) that the human brain has separate mechanisms for identifying curved shapes and angular shapes, and that these mechanisms tend to interfere or compete with each other.

Takahashi reached this conclusion after trying to deconstruct the illusion across three experiments. He showed participants several variations on the illusion, changing details like the height of the curves, the color of the background (black, white or gray), and whether the lines changed color at the peak of the curve or on either side of it. He found that the only conditions that made the curved lines reliably appear zigzagged were: when the lines had a gentle curve, when the lines changed color directly before and after the peaks or valleys of each curve, and when the lines appeared over a gray background that contrasted the light and dark tones of each line.

The final image of the illusion reflects these findings: Every line appears curved when seen over the white and black backgrounds, while in the gray, middle section, only lines that change color right before and after the peaks of the curves seem to be zigzagged. When the two colors meet at the curve's peak, they create a subtle vertical line that exaggerates the peak's sharpness.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Takahashi hypothesized that when the curve- and angle-perception mechanisms of the brain work side by side with similar inputs like these, angles take priority.

"We propose that the underlying mechanisms for the gentle-curve perception and those of obtuse-corner perception are competing with each other in an imbalanced way and the [perceptions of corners] might be dominant in the visual system," Takahashi wrote.

So, whoever had money on corners in the curves vs. corners matchup wins.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.