Giant Penguin: This Ancient Bird Was As Tall As a Refrigerator

The fossils of a refrigerator-size penguin were so gargantuan that the scientists who discovered them initially thought they belonged to a giant turtle. The ancient behemoth is now considered the second-largest penguin on record.

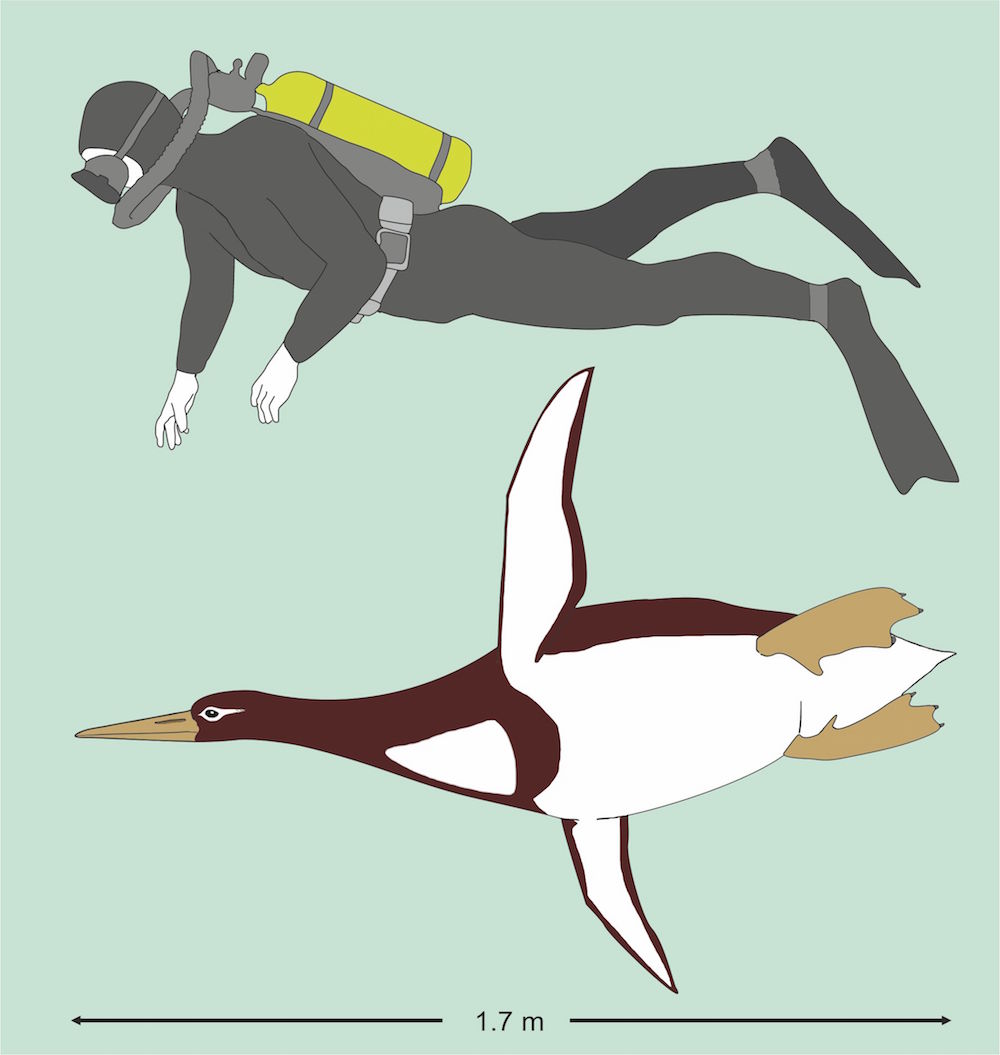

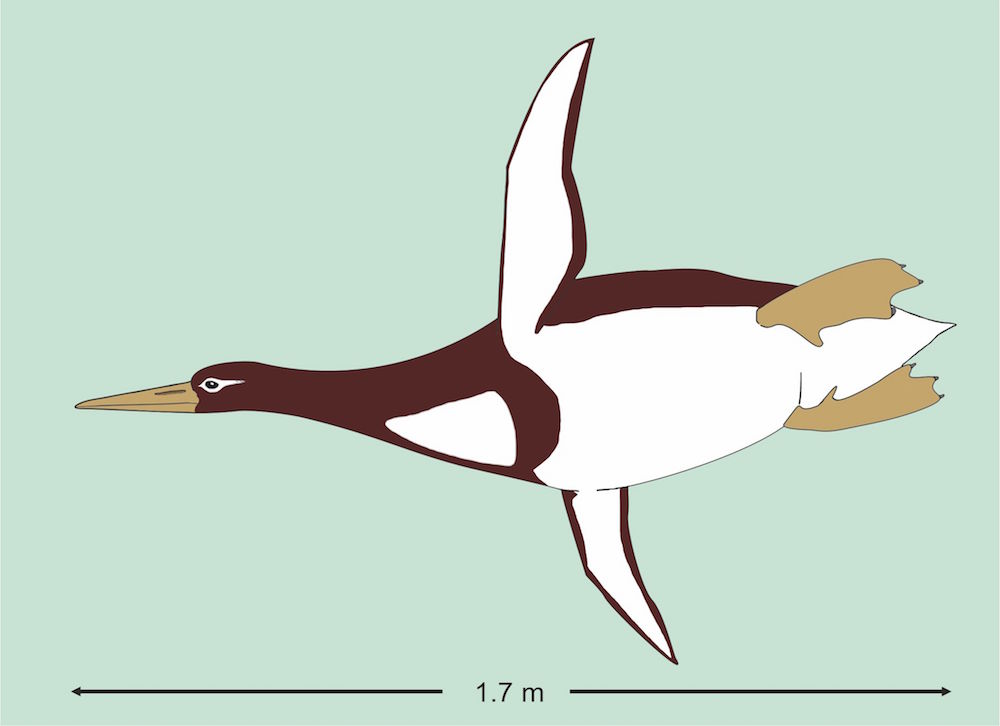

The newfound penguin species would have stood nearly 6 feet tall (1.8 meters) and weighed about 220 lbs. (100 kilograms) during its heyday tens of millions of years ago.

The bird's gigantism indicates that "a very large size seems to have developed early on in penguin evolution, soon after these birds lost their flight capabilities," said study co-lead researcher Gerald Mayr, a curator of ornithology at the Senckenberg Research Institute, in Germany. [In Photos: The Amazing Penguins of Antarctica]

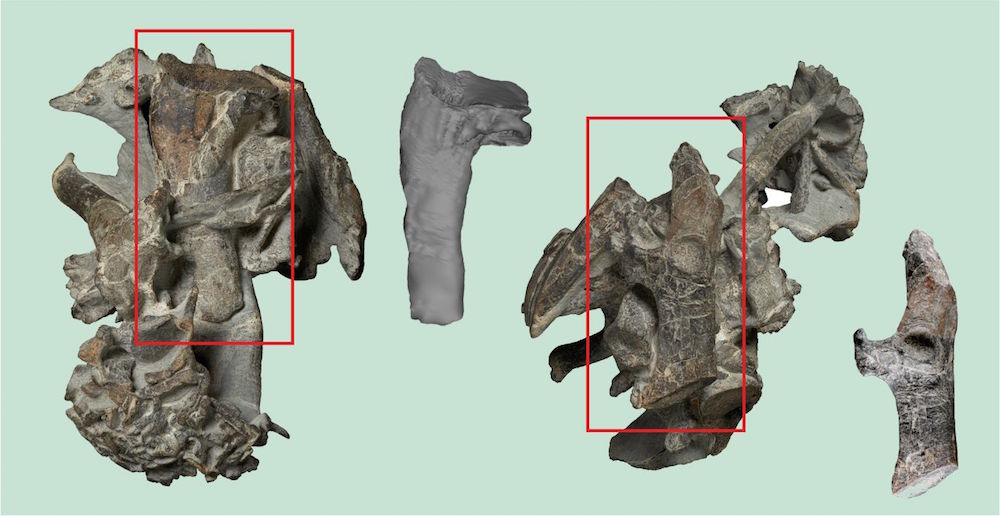

At first, the researchers thought the penguin fossils belonged to a turtle, said study co-lead researcher Alan Tennyson, a vertebrate curator at the Museum of New Zealand (Te Papa Tongarewa), who discovered the fossil with paleontologist Paul Scofield on a beach in New Zealand's Otago province in 2004.

But shortly after a fossil technician began preparing the specimen in 2015, he found a part of the shoulder blade, known as the coracoid, which revealed that the fossils came from a penguin, Tennyson told Live Science.

Further analysis dated the penguin to between 55 million and 59 million years ago, meaning that it lived a mere 7 million to 11 million years after an asteroid slammed into Earth and killed the nonavian dinosaurs, Mayr said.

The researchers named the late-Paleocene penguin Kumimanu biceae. Its genus name, Kumimanu, was inspired by the Maori indigenous culture of New Zealand. In the Maori culture, "kumi" is a mythological monster, and "manu" is the Maori word for "bird." The species name, biceae, honors Tennyson's mother, Beatrice "Bice" A. Tennyson, who encouraged him to pursue his interest in natural history.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

K. biceae didn't look much like modern penguins. Although researchers could not find its skull, they "know from similarly aged fossils that the earliest penguins had much longer beaks, which they probably used to spear fishes, than their modern relatives [do]," Mayr told Live Science. Like its modern cousins, however, K. biceae would have already developed typical penguin feathers, waddled with an upright stance and sported flipper-like wings that helped it swim, he added.

Researchers have discovered other ancient penguin fossils in New Zealand, including those of Waimanu manneringi, which lived about 61 million years ago. However, the largest penguin on record is Palaeeudyptes klekowskii, which lived about 37 million years ago in Antarctica. P. klekowskii stood about 6.5 feet (2 m) tall and weighed a whopping 250 lbs. (115 kg), according to a 2014 study in the journal Comptes Rendus Palevol (Palevol Reports).

Given that the Antarctic penguin was larger than K. biceae, it's likely that "giant size evolved more than once in penguin evolution," Mayr said.

K. biceae is a "cool fossil," said Daniel Ksepka, a curator at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, who was not involved in the research. "It's very old; it's almost as old as the oldest known penguins anywhere," Ksepka told Live Science. "That shows that [penguins] got big really quickly. And it all seems to have happened in New Zealand." [Photos of Flightless Birds: All 18 Penguin Species]

But why was New Zealand a penguin paradise? The archipelago was surrounded by fish for penguins to eat, and it originally had no native mammals (although today it's home to many sheep, weasels and domestic pets), meaning that there were no predators to bother the penguins when they came ashore to molt their feathers and lay eggs, Ksepka said.

The study was published online today (Dec. 12) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.