The Arctic Ice Is Dying

The Arctic "shows no sign of returning to [the] reliably frozen region of past decades," according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) annual Arctic Report Card.

The 2017 report card primarily covers the period from October 2016 to September 2017. NOAA releases its report card each December to sum up the previous October-to-September year in the northern latitudes. The report card puts the year's developments into context with the longer-term trends observed in the region. After this past Arctic summer — which was relatively cool in the context of the past several decades — failed to produce stable sea ice or other positive indicators of a healthy ecosystem, the authors of this year's report card suggest that the region has reached a "new normal" of thin, weak sea ice.

Even cool years are now unlikely to return the Arctic to its healthy status quo; the region is just too damaged to go back to what was previously considered to be normal, they wrote. [Gallery: An Expedition into Iceberg Alley]

"Arctic paleo-reconstructions, which extend back millions of years, indicate that the magnitude and pace of the 21st century sea-ice decline and surface ocean warming is unprecedented in at least the last 1,500 years and likely much longer," they wrote.

To understand the Arctic climate in a deep way, you have to understand its four key elements: air, water, land and ice.

Here's what happened with each of those pieces of the Arctic between October 2016 and September 2017.

The air

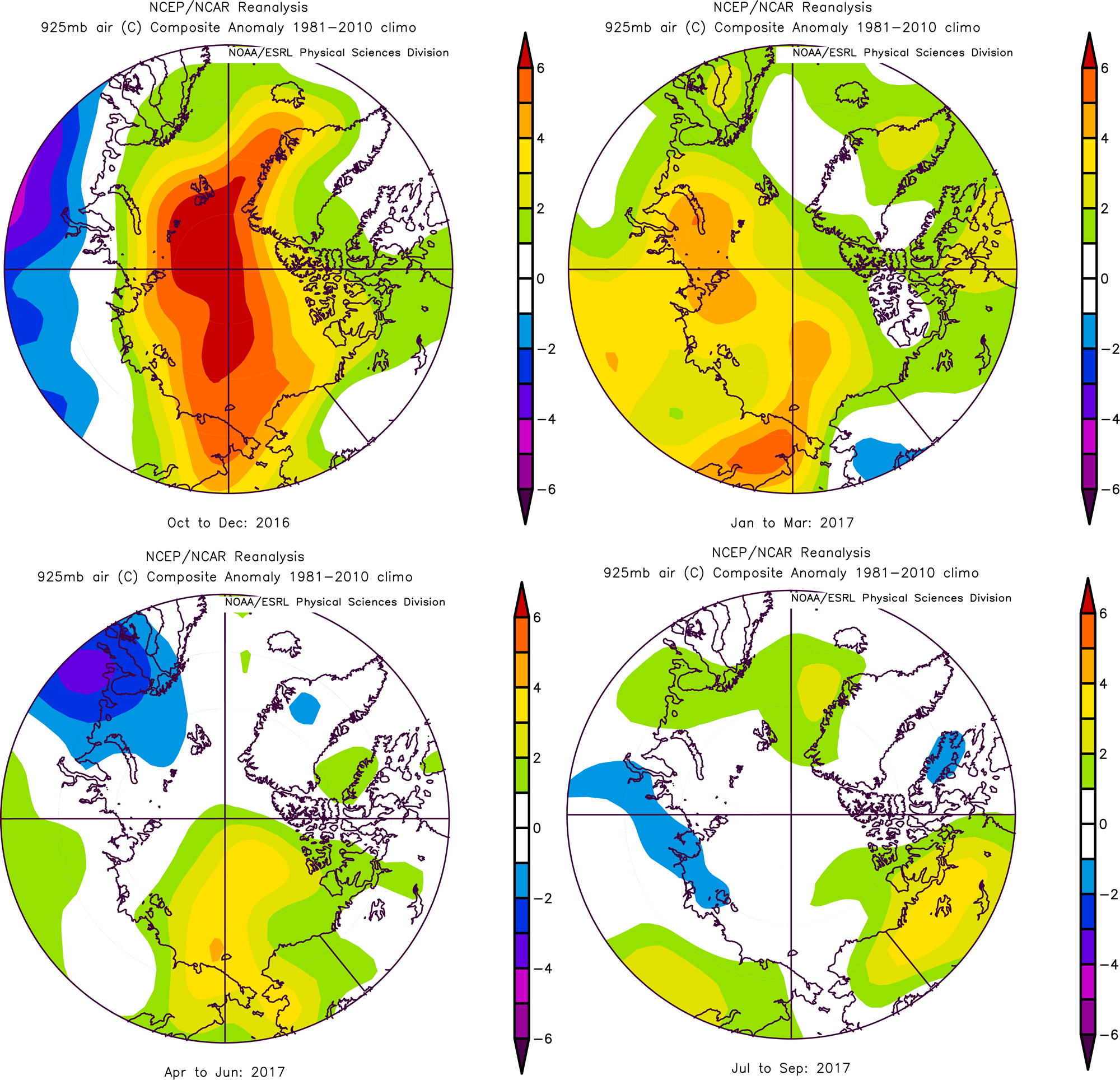

Last year's 2015-2016 report card showed that year was "by far" the warmest in the observational records, which date back to 1900. The 2016-2017 period was significantly cooler — but still the second-hottest year since 1900.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most of that heat was packed into the beginning of the year, leading to a warm Arctic autumn and winter.

Spring and summer 2017, on the other hand, were abnormally cool for the modern era. Summer, in particular, was out of step with recent trends, with temperatures comparable to those before extreme Arctic warming kicked in during the 1990s, the report's authors wrote. The only exceptional Arctic summer weather turned up in Alaska and northwestern Canada, where July was the warmest on record.

The water

Sunlight drives warming in the Arctic ocean. The water's temperature varies each summer with the amount of sunlight that makes it through the atmosphere and ice cover to strike the sea surface, the report authors wrote.

That means that when there's less ice and less cloud cover, the northern ocean warms faster.

Arctic researchers make their most meaningful sea-surface temperature measurements in August, after the end of a full summer of warming but before the September cool sets in.

In some areas, August 2017 was almost 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (3 degrees Celsius) cooler than August 2016. But 2017 sea-surface temperatures still joined a long-term warming trend: August 2017 was 5.4 degrees F warmer than August 2012, the authors wrote. That's a big deal, because 2012 saw the lowest summer sea-ice minimum ever recorded in the Arctic and, absent long-term warming, should have been a warmer year underwater. [Gallery: Scientists at the Ends of the Earth]

That long-term warming has sustained a bloom of life in Arctic waters, as critters ranging from algae to large predator fish move into waters that had once been too cold for them, according to the report.

The land

Data about the Arctic land isn't as up-to-the-minute as data about Arctic ice, air and sea. But here's what researchers do know, and wrote in this year's report:

Permafrost — the ancient layer of wet, frozen earth in the northern latitudes — is warming and softening. In summer 2016, the permafrost 66 feet (20 meters) below the surface reach its warmest temperatures since 1978. All around the Arctic, the ground has gotten mushy as thicker and thicker layers of slush form beneath the Earth.

At tha same time, in 2015 and 2016, there was a spike in "greenness" in the Arctic — areas that look green in satellite views because of plants — after a several-year decline. One positive sign on land was an above-average snow cover in the Asian Arctic, as measured by satellites — the second highest ever. It was the first "positive anomaly" in the snow record since 2005.

The ice

The final and most important element of the Arctic, the axis around which all the other elements turn, is the sea ice. When the sea ice is expansive and healthy, it keeps the oceans from warming and reflects sunlight into space, protecting the whole planet from warming.

Arctic sea ice pulses every year, growing each winter to double or triple its extent of the previous summer, the authors wrote. In recent decades, though, it has been in a state of overall decline.

For years, scientists have warned that the first completely ice-free summer in the Arctic was coming. Now, it's the official position of NOAA that the Arctic shows no signs of ever returning to its year-round comfortably iced-over state.

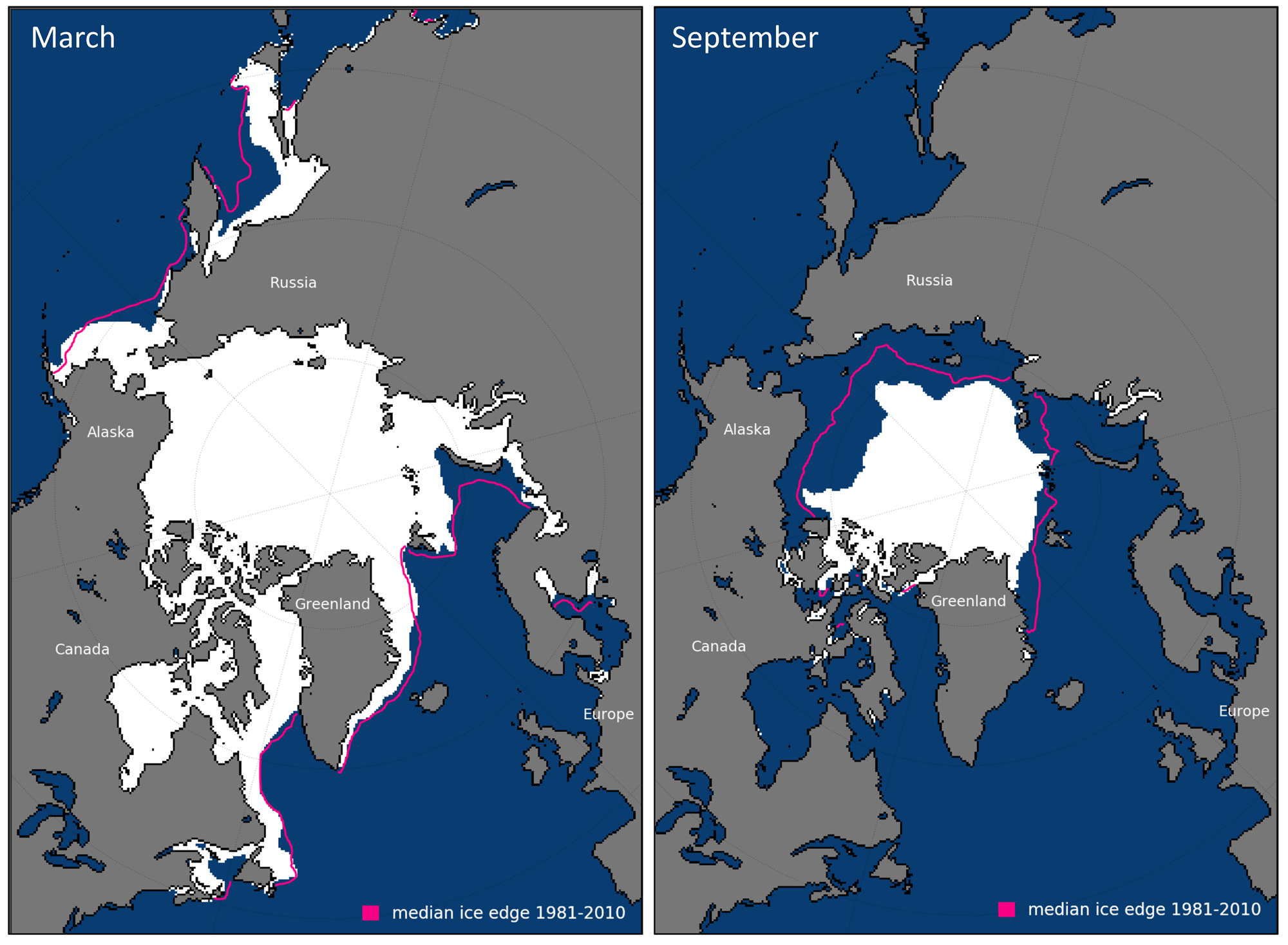

Winter 2016-2017 saw the lowest maximum sea-ice extent in satellite records dating back to 1979 — the third record-low year in a row. Sea ice maxed out on March 7, 2017, at 5.5 million square miles (14.2 million square kilometers) — 8 percent below the 1981-2010 average.

Sea ice then started to shrink five days earlier than the 1981-2010 average, reaching its summer minimum on Sept. 13, at 1.8 million square miles (4.6 million square km). That extent was slightly greater than the 2016 minimum and 25 percent lower than the 1981-2010 average.

"The 10 lowest September extents," the report card authors wrote, "have occurred in the last 11 years."

In any given month of the year, they calculated, sea-ice extents are declining at a rate of about 13.2 percent per decade.

The ice that remains is also thinner, younger and less stable than it's been in the past. Back in the 1980s, just 55 percent of the peak ice each winter was new that year, and 16 percent of the ice had hung around for more than four years. In 2017, a full 79 percent of the winter maximum was made up of newly frozen ice, and only 0.9 percent of the maximum was more than four years old.

When ice doesn't age, it doesn't have time to grow thick. That long-term thinning trend weakens the ice, making it more difficult for it to stabilize or grow during cooler years, with long-term implications for the health of the Arctic and, in turn, the entire planet, the researchers said.

Originally published on Live Science.