Poop Proof: Ancient Greeks Suffered from Gut Parasites

Thousands of years ago, the Greek physician Hippocrates, widely considered to be the father of modern medicine, wrote about diseases he and his students observed and treated, including intestinal parasites.

Modern scholars suspected that parasitic worms described in the medical text "Hippocratic Corpus" were actually roundworms, pinworms and tapeworms, but there was no physical evidence to back that up.

However, archaeologists recently discovered remnants of ancient poo that bolster historians' theory about Hippocrates' diagnostic prowess.

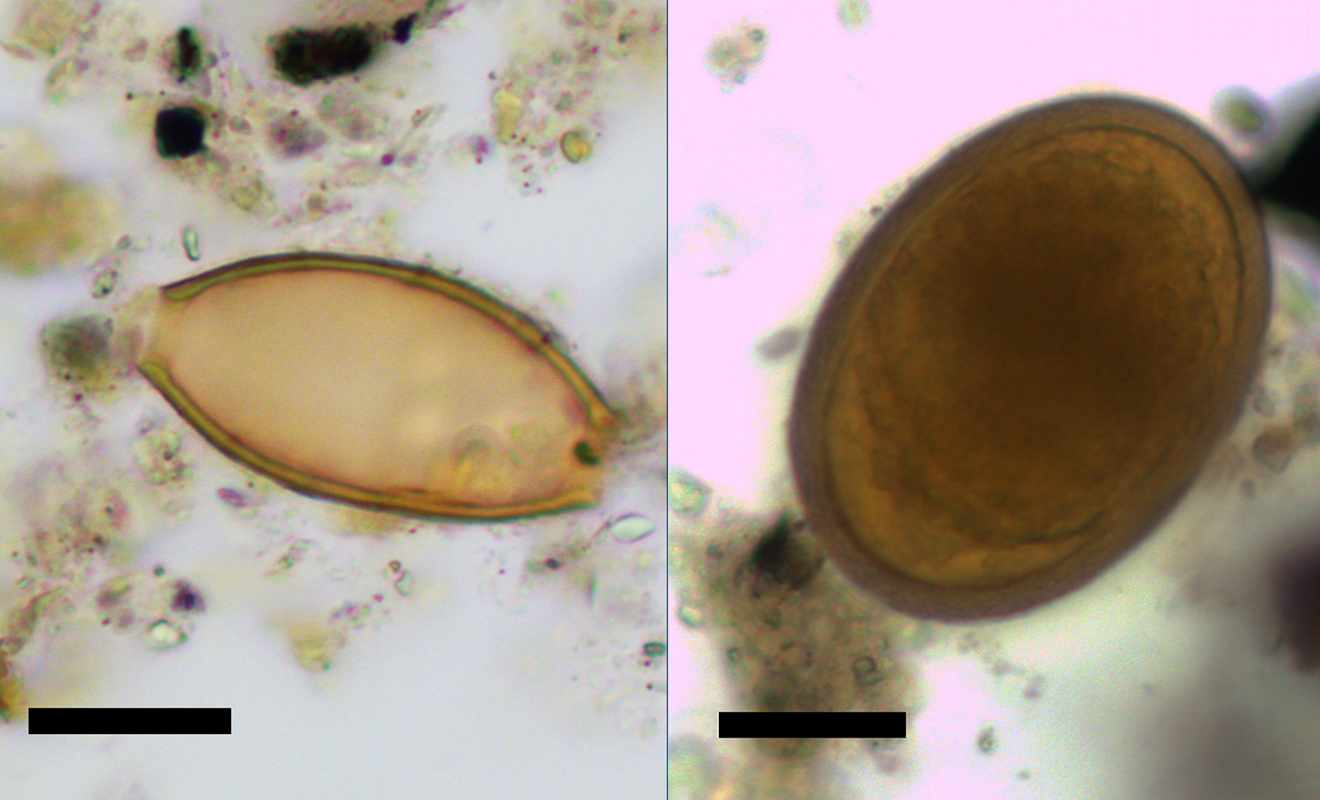

The poop — by now decomposed into soil — was found adhering to pelvic bones from a burial site on the Greek island of Kea, which holds remains dating from about 4,000 B.C. in the Neolithic period to A.D. 330. The researchers found that the fecal remnants contained eggs from two types of intestinal parasites — whipworm and roundworm — giving a modern name to Hippocrates' ancient diagnoses from 2,500 years ago and providing the earliest evidence of parasitic worms in the people of ancient Greece, the study authors reported. [Myth or Truth? 7 Ancient Health Ideas Explained]

"Finding the eggs of intestinal parasites as early as the Neolithic period in Greece is a key advance in our field," study co-author Evilena Anastasiou, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cambridge in England, said in a statement.

In ancient Greek medical texts, three terms were typically used to describe parasitic worms: Helmins strongyle described "a large round worm," Helmins plateia referred to "a flat worm," and Ascaris was "a small round worm." Scholars suspected these names referred to parasites currently known as roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), tapeworms in the Taenia genus and pinworms (Enterobius vermicularis), the researchers wrote in the study.

To investigate that interpretation, the scientists analyzed 25 burials spanning 4,000 years, removing sediment that contained traces of decomposed human excrement. They found evidence of roundworm or whipworm eggs in four individuals, confirming that Hippocrates was probably talking about roundworms in his 2,500-year-old medical texts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The Helmins strongyle worm in the ancient Greek texts is likely to have referred to roundworm, as found at Kea," the study's lead author Piers Mitchell, a lecturer in biological anthropology at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement.

However, Hippocrates may have conflated two common parasites in his texts, the researchers proposed.

"The Ascaris worm described in the ancient medical texts may well have referred to two parasites, pinworm and whipworm, with the latter being found at Kea," Mitchell added.

One possible explanation for why only whipworm and roundworm eggs survived the test of time could lie in their robust outer membranes, which shielded the eggs from destruction. Meanwhile, the more delicate eggs of other intestinal parasites, such as hookworms and pinworms, were broken down, the researchers reported.

Previous research suggested that whipworms and roundworms have parasitized people throughout human evolution, and when the first settlers arrived on the Greek island of Kea, those intestinal parasites likely arrived with them, the scientists explained in the new study. In addition to confirming Hippocrates' description of roundworms, their findings also suggested that whipworms were present as parasites in the region thousands of years ago, the study authors reported.

"Until now we only had estimates from historians as to what kinds of parasites were described in the ancient Greek medical texts. Our research confirms some aspects of what the historians thought, but also adds new information that the historians did not expect, such as that whipworm was present," Mitchell said.

"This research shows how we can bring together archaeology and history to help us better understand the discoveries of key early medical practitioners and scientists," he added.

The findings were published online today (Dec. 14) in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.