Our solar system is not alone atop the planet-harboring heap anymore.

Scientists have discovered another world orbiting the star Kepler-90, bringing that system's tally of confirmed planets to eight — the same number as in Earth's solar system (at least according to the International Astronomical Union, which stripped Pluto of its "ninth planet" status back in 2006).

That's one more than the previous extrasolar record, which had been held jointly by Kepler-90 and the TRAPPIST-1 system. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

The research team found the new planet, known as Kepler-90i — as well as another world in a different system — after analyzing archival data from NASA's Kepler mission using Google machine-learning techniques.

"Just as we expected, there are exciting discoveries lurking in our archived Kepler data, waiting for the right tool or technology to unearth them," Paul Hertz, director of NASA's Astrophysics Division in Washington, D.C., said in a statement. "This finding shows that our data will be a treasure trove available to innovative researchers for years to come."

The Kepler space telescope launched in March 2009. During its four-year original mission, the spacecraft scanned 150,000 stars continuously, searching for the tiny brightness dips caused by planets crossing the stars' faces. In 2014, Kepler shifted to a second mission known as K2, during which it hunts for exoplanets on a more limited basis but also makes a variety of other observations.

This planet-hunting work has been incredibly successful. To date, Kepler has discovered more than 2,500 confirmed alien worlds — about two-thirds of all known planets beyond our solar system — as well as more than 2,000 "candidates" that await confirmation by follow-up observations or analysis. (The vast majority of these finds have come from the original-mission observations; the K2 confirmed-planet tally stands at 184.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the two new discoveries suggest that many more alien worlds may lurk undiscovered in Kepler's data sets.

Researchers Christopher Shallue and Andrew Vanderburg — a senior software engineer with Google AI and an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin, respectively — trained a computer to recognize weak, as-yet-unnoticed exoplanet signals in Kepler data. The duo used a machine-learning approach, basing it on the networks of neurons that populate the human brain.

"In my spare time, I started googling for ‘finding exoplanets with large data sets’ and found out about the Kepler mission and the huge data set available," Shallue said in the same statement. "Machine learning really shines in situations where there is so much data that humans can't search it for themselves."

The scientists tested their software on 15,000 previously vetted Kepler signals, including both confirmed detections and false positives. Shallue and Vanderburg found that the artificial neural network identified such signals correctly 96 percent of the time. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

So the researchers directed the network to search for additional weak signals in 670 star systems already known to host multiple planets, reasoning that such systems had a good chance of hosting additional, undiscovered worlds.

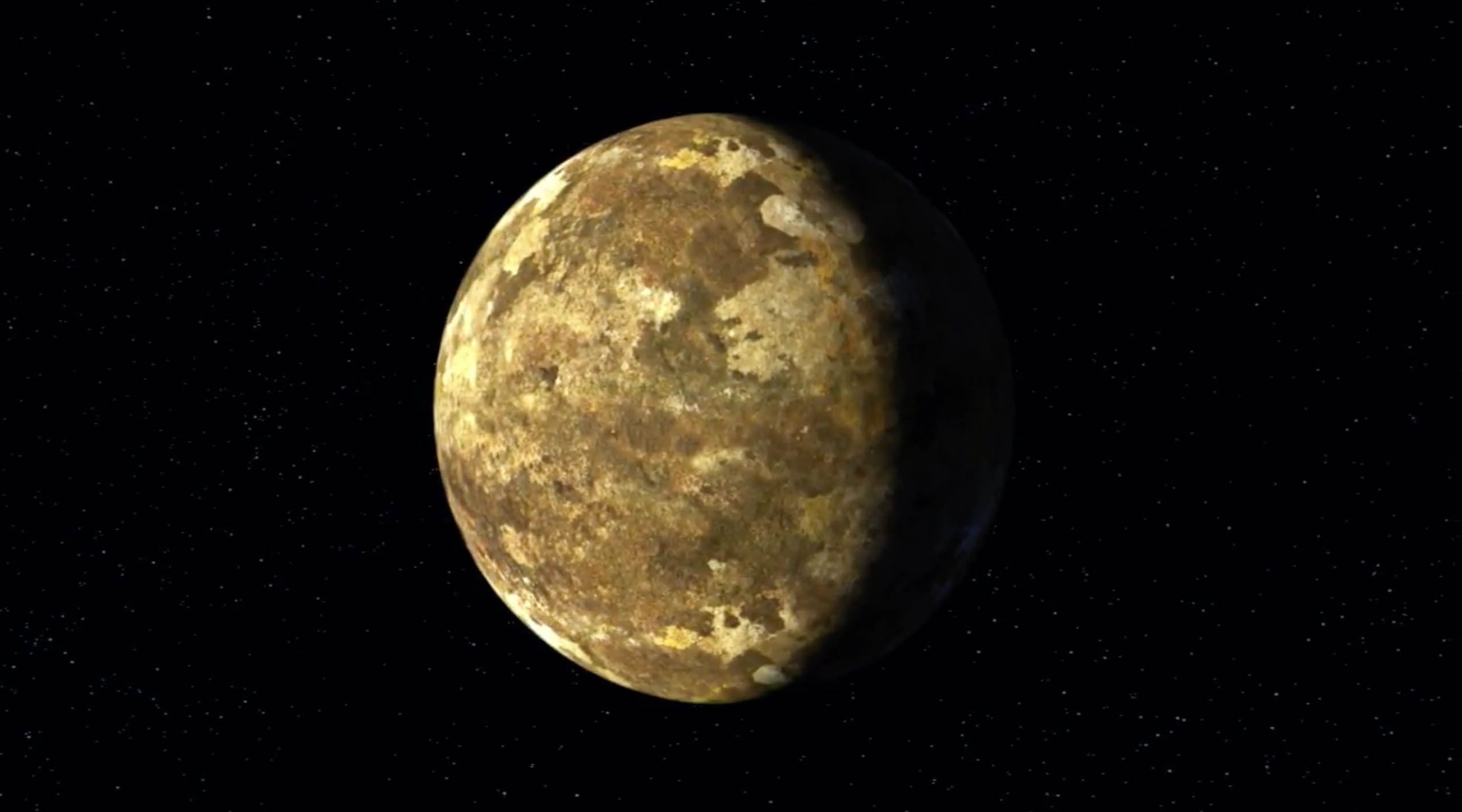

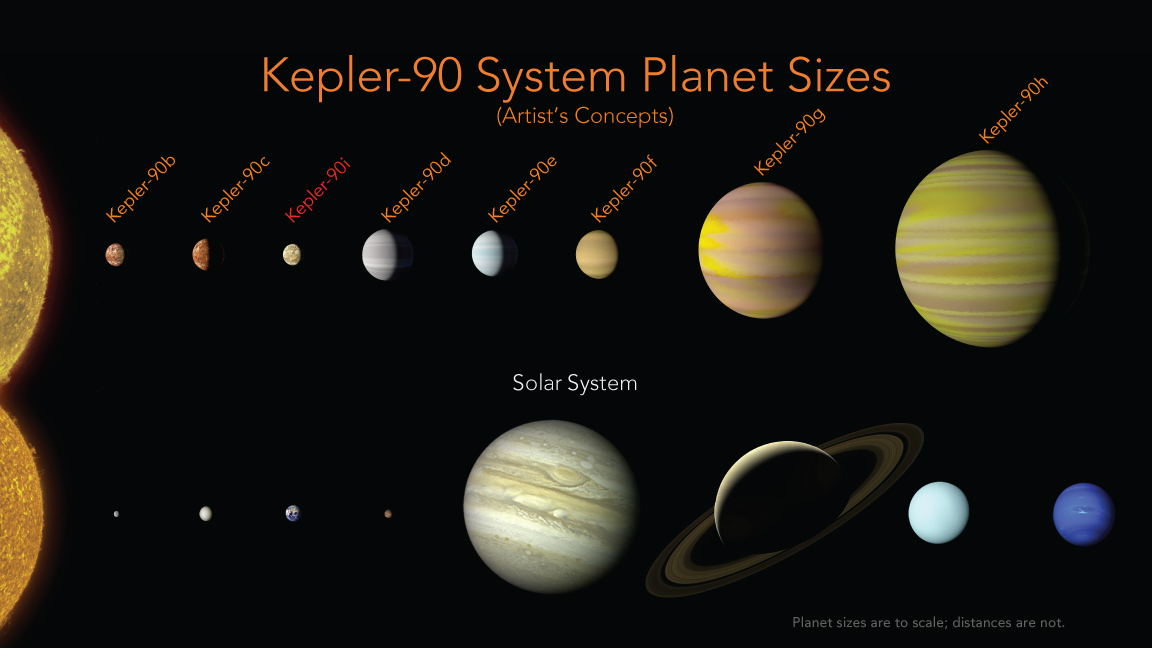

And they found two such planets, including Kepler-90i, which lies about 2,545 light-years from Earth. Kepler-90i is probably rocky, like Earth, and it's the third world out from its star, which is a bit hotter than our sun. But the similarities with our home planet probably end there: Kepler-90i completes one orbit every 14.4 Earth days and is therefore probably much too hot to host life. Indeed, average surface temperatures on the planet probably hover around 800 degrees Fahrenheit (430 degrees Celsius), Vanderburg said.

And the Kepler-90 system is far from an exact simulacrum of our own. Though its inner planets are rocky and outer ones are gaseous, this system is much more compact than our solar system — all eight Kepler-90 worlds are closer to their star than Earth is to the sun, the researchers said.

These planets may have migrated inward, toward their host star, over time, they added. But the current configuration, strange as it may seem to us, appears to be relatively stable, Vanderburg said.

The star may host even more planets, he added.

"There's a lot of unexplored real estate in the Kepler-90 system, and it would almost be surprising to me if there weren't any more planets around this star," Vanderburg said during a news conference today (Dec. 14).

The other newfound world, known as Kepler-80g, is the sixth planet known in its system, which is centered around a dwarf star that lies about 1,160 light-years from the sun. Again, this extrasolar system is quite compact; Kepler-80g also takes about two Earth weeks to complete one orbit.

Such work is probably just the beginning for machine-learning exoplanet discovery; Shallue and Vanderburg intend to apply their techniques to Keplerf's entire data set.

"These results demonstrate the enduring value of Kepler’s mission," Kepler project scientist Jessie Dotson, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said in the same statement.

"New ways of looking at the data — such as this early-stage research to apply machine learning algorithms — promises to continue to yield significant advances in our understanding of planetary systems around other stars," Dotson added. "I'm sure there are more firsts in the data waiting for people to find them."

The new study has been accepted for publication in The Astronomical Journal.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.