Photos: Children's Graves Discovered in Ancient Egypt

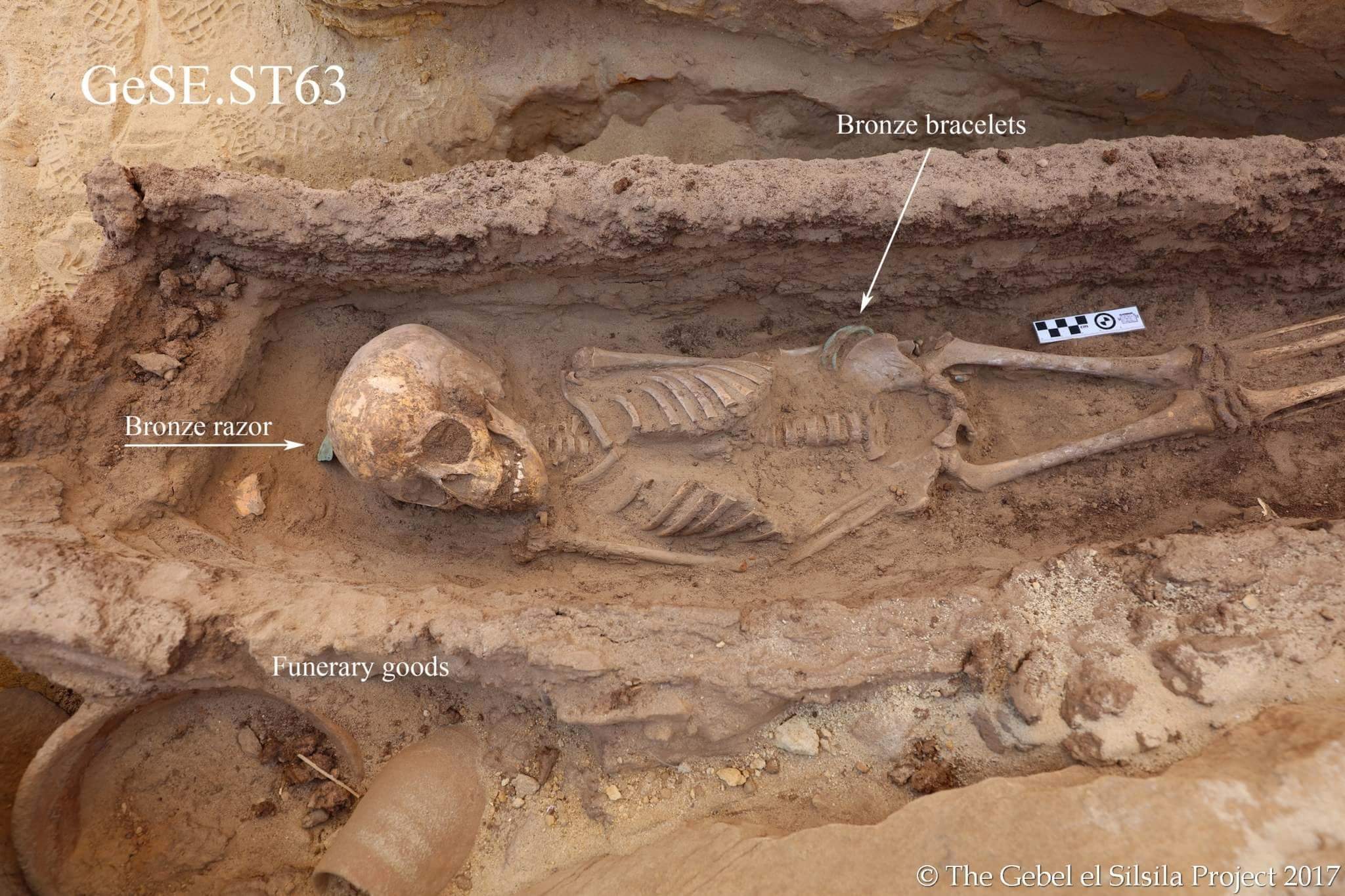

A Child's Grave

The body of a child between the ages of 6 and 9 found at Gebel el Silsila, an ancient Egyptian quarry site. The child's coffin has long since been destroyed by flooding and beetles, but he or she was buried with multiple plates and vessels as well as bronze ornaments, including bracelets, scarabs and a nefer amulet, commonly used to wish the deceased good tidings in the afterlife. [Read more about the ancient burials found in Egypt]

Bronze Bracelet

A close-up of one of the bronze bracelets found in the tomb of the 6- to 9-year-old child. The grave was one of four intact child burials discovered at Gebel el Silsila. It and the others date to the Thutmosid period, or the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt (sometimes called Thutmosid because there were four pharaohs named "Thutmose" in the dynasty). That places the age of this bracelet and the other artifacts between about 1550 B.C. and 1292 B.C.

Bronze razor

A bronze razor found interred with a child between the ages of six and nine at Gebel el Silsila. This site was a quarry for the tombs and temples of Upper Egypt, but discoveries like this (and many rock-cut tombs) suggest the place was a bustling hub of activity where people lived as well as worked.

Burial bowls

Bowls found buried with a 6- to 9-year-old child. Other ceramics in the grave included beer jars, wine vessels and plates.

System of Crypts

An image showing the location of the tomb of a toddler who died between the ages of 2 and 3 and an adult crypt. Previously, more than 40 tombs have been discovered at Gebel el Silsila, but most were looted in antiquity and are empty of coffins or burial goods.

A Child's Bones

The body of a toddler, age 2 or 3, found buried in the remnants of a linen shroud and surrounded by organic matter that might have once been a wooden coffin. The child's crypt was sealed with plaster, but there was nothing buried within the grave other than the body.

Mysterious burials

A view of the tomb of the six- to 9-year-old child from Gebel el-Silsila. The bronze razor is visible, tucked against the top of the child's skull.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A Third Grave

A third child's grave from Gebel el-Silsila. The occupant was probably between the ages of five and eight at death. This child was buried "without obvious care" in a quarried area of the site, according to archaeologists, and was not found with grave goods. Evidence on the bones suggests the child may have been ill before death.

Grave Scan

A three-dimensional computer-generated scan of the grave of the 2- or 3-year-old from Gebel el-Silsila.

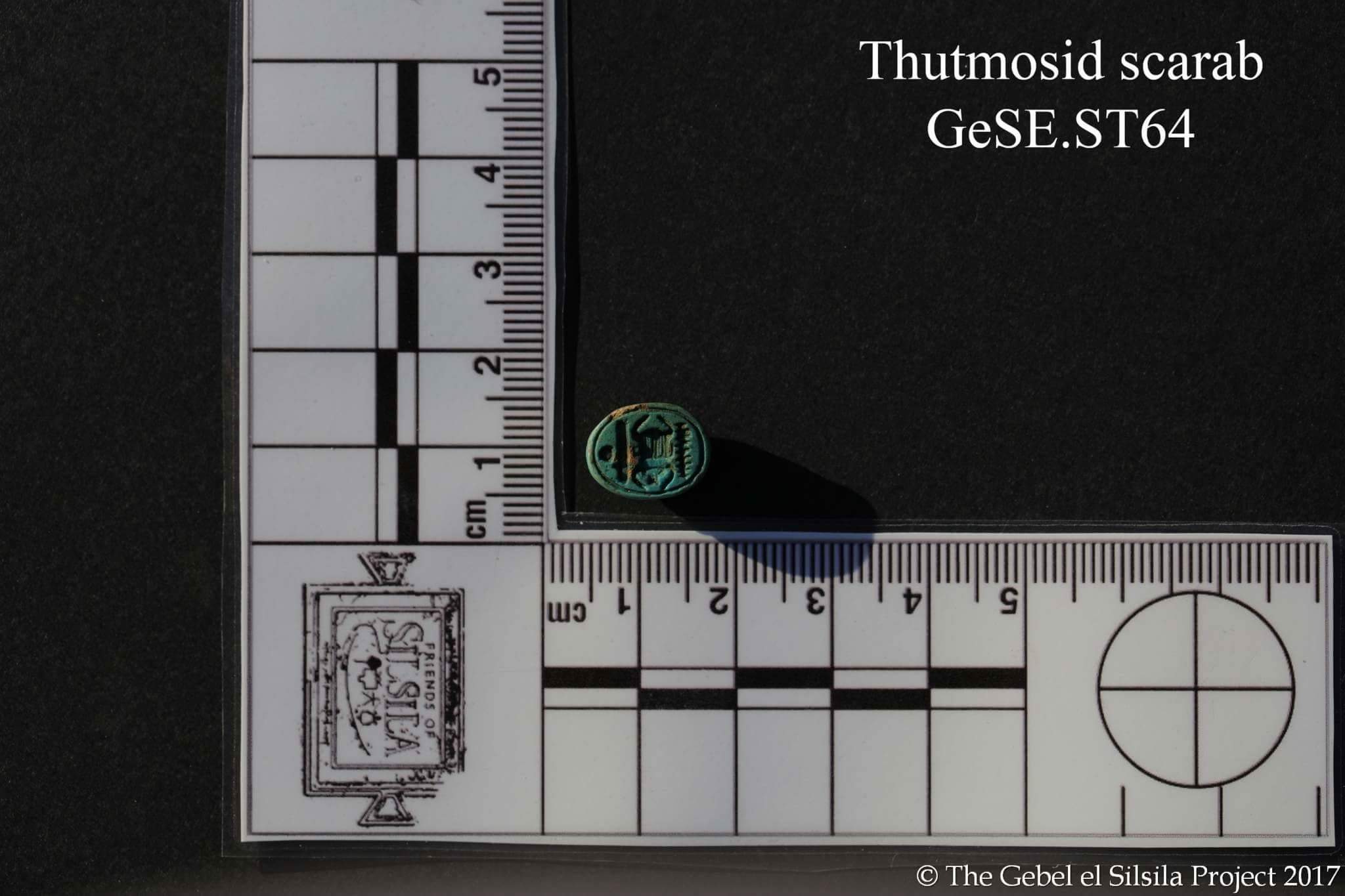

Scarab

A scarab amulet found in the grave of a fourth child, probably between 5 and 8 years old at death, who was found wrapped in linen and laid on a reed mat within a crypt. This child was buried with three scarab amulets, including this one engraved with a royal name of the Thutmosid period.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.