The 10 Weirdest Sea Monsters of 2017

Sea Monsters of 2017

One fish, two fish, dead fish, new fish.

That's right, kids — it's time to count down the most incredible marine-life discoveries of 2017.

Kick off your shoes and slide into your wetsuit while we recount the bucktoothed sharks, cosmic jellyfish, boat-eating worms, luminous slime sacks and deep-sea superpredators that kept this year packed to the gills with undersea excitement.

Bucktoothed ghost shark

A new species of ghost shark discovered near South Africa set records this January. At nearly 3 feet (about 1 meter) in length, the creature is the second-largest species of ghost shark ever discovered, according to researchers at the Pacific Shark Research Center at the Moss Landing Marine Laboratories in California.

The species, Hydrolagus erithacus, marked the 50th recorded species of ghost shark and the third that fits into the genus Hydrolagus, which means "water rabbit." While H. erithacus is decidedly more shark than rabbit, researchers noted that ghost sharks are not actually sharks at all. Rather, they are large, cartilaginous fish related to both sharks and rays. Unlike true sharks, ghost sharks (also known as chimaeras or ratfish) propel themselves with their large pectoral fins, rather than their tails.

Ghost sharks: neither ghosts nor sharks. Talk amongst yourselves. [Read the full story on the bucktoothed ghost shark.]

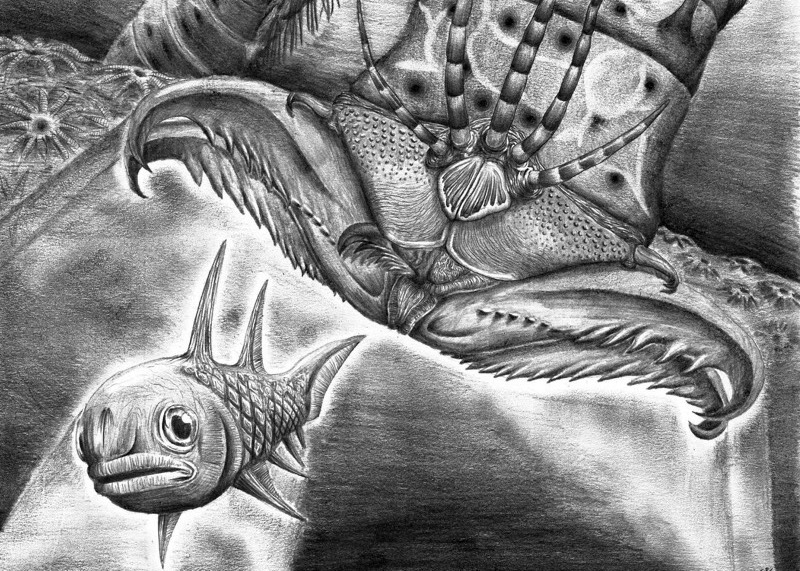

Cannibal corpse worm with monster jaws

The fossilized jaws of a giant marine worm (or polychaete) called a Bobbit worm were discovered near the town of Moosonee on Hudson Bay in Ontario, Canada, in February. This granddaddy of all marine worms lived some 400 million years ago, making it the world's oldest worm. Based on its massive jaws, it likely stretched more than 3 feet long. Because of the worm's formidable size, researchers named it Websteroprion armstrongi in honor of Cannibal Corpse bassist Alex Webster — a so-called "giant" of a bass player.

Bobbit worms are part of the Eunicidae family of polychaetes. Other giant eunicids lurk in ocean beds around the world today, where they bury most of their bodies in the sand before shooting out for sneak attacks on unsuspecting prey. Modern eunicids can grow to be up to 10 feet (3 m) long, but other known worms of W. armstrongi's day tended to be significantly smaller. According to study leader Mats Eriksson, of Lund University in Sweden, "The new species demonstrates a unique case of polychaete gigantism in the Palaeozoic era." [Rock out with the full story on the Cannibal Corpse Bobbit worm here.]

"Cosmic" jellyfish in the ocean's deepest reaches

This jellyfish is far out, dude — and far under. Spotted near a previously unexplored seamount roughly 9,800 feet (3,000 m) below sea level in a remote region of the Pacific Ocean near American Samoa, the ethereal invertebrate looks like a UFO and may be a brand-new species of jellyfish.

It's hard to tell, though, as the saucer-shaped drifter was observed only via a remotely operated underwater vehicle during a deep-dive expedition by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Getting the critter under a microscope and running genetic analyses could help reveal its origins — and maybe a lot more, the researchers said. "As we collect more observations like this one, we can begin to get a clearer picture of life in the midwater — perhaps the largest biome on the planet," said Michael Ford, a conservation biologist with NOAA's Northwest Fisheries Science Center. [Watch the cosmic jellyfish in action in this stellar video.]

Giant, slimy shipworm with a tough, tubular shell

The slimy mollusks known as shipworms have been making life harder for sailors at least since 412 B.C., when ancient records reveal complaints about the little wood-eating pests infesting and ruining entire boats. Giant shipworms called Kuphus polythalamia, however, have remained an unseen mystery for hundreds of years — until April.

Researchers collected five giant shipworms of the species from a shallow bay in the Philippines, finally studying the elusive creature. Unlike small, wood-infesting shipworms, K. polythalamia can measure 3 to 5 feet (1 to 1.5 m) in length, live facedown in marine mud, and surround itself in hard, tubular shells that look like elephant tusks. Study co-author Margo Haygood, a research professor in medicinal chemistry at the University of Utah College of Pharmacy, likens the discovery to spotting "a unicorn for marine biologists." [Watch researchers pour a giant shipworm out of its shell for examination.]

World's deepest-living predator (it's terrifying)

Scientists aboard a research vessel were trawling for fish near eastern Australia when they accidentally pulled up this: a fang-faced monster that has the body of an eel, the face of a lizard and an impressive reputation as the world's deepest-living predator.

Known as Bathysaurus ferox (literally meaning "fierce deep-sea lizard"), the so-called lizard fish has an MO of burying itself on the deep seafloor, 3,300 to 8,200 feet (1,000 to 2,500 m) below the water's surface. When unsuspecting prey swims by, B. ferox darts out of the sediment and snatches up the meal in its formidable jaws. "Once it has you in its jaws, there is no escape: The more you struggle, the farther into its mouth you go," Asher Flatt, the vessel's onboard communicator, wrote in a blog post.

Oh, also, it's a hermaphrodite (meaning it has both ovarian and testicular tissues in its reproductive organs). That means any B. ferox can mate with any other B. ferox it meets, giving the species a survival advantage in the sparsely populated deep ocean. [Read more about that here.]

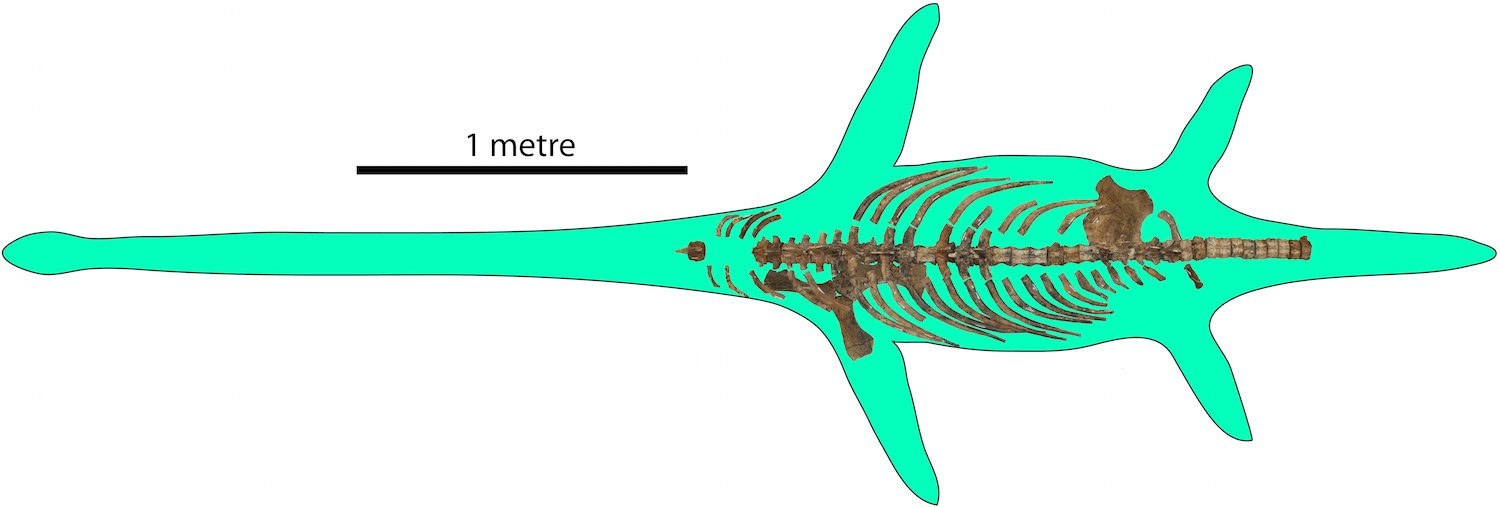

Car-size "Loch Ness monster"

When you imagine the legendary Loch Ness monster, you probably see something that looks like a plesiosaur — a long-necked, aquatic dinosaur with four flippers and a broad, crocodile-like body (kilt and flannel cap optional). Earlier this year, on Aug. 23, researchers presented their findings of a 76-million-year-old plesiosaur skeleton recovered from Alberta, Canada. The river-dwelling reptile would have been about "the size of a car" — measuring between 13 and 16 feet (4 and 5 m) long when it was alive, the researchers from the University of Calgary said.

Large as this sounds, the plesiosaur in question was likely not even fully grown when it died, and could have grown several feet longer still. Even so, the specimen was a small fry compared with its ocean-dwelling plesiosaur cousins, which are thought to have been up to 50 feet (15 m) long, the researchers said, putting them closer to the length of modern buses. Read more about the 76-million-year-old Nessie relative.]

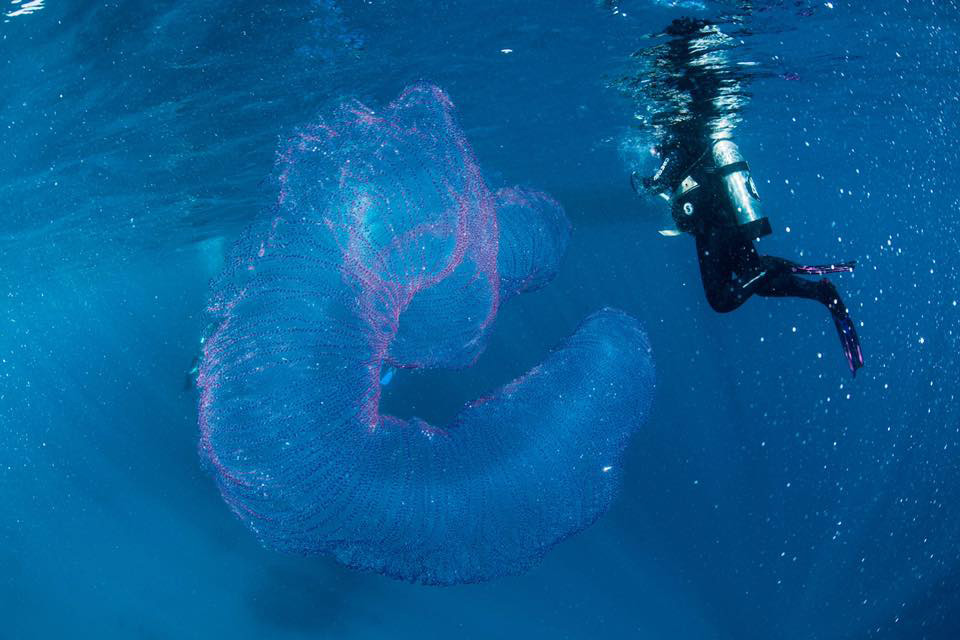

Mysterious, Slinky-like sac of slime

A glowing, swirling, gelatinous blob photographed by scuba divers off the coast of Australia captured the internet's attention in September. Was the Slinky-like sac some sort of sea monster? An enormous worm? Or perhaps a creature totally new to science? Rebecca Helm, a jellyfish biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, revealed the answer: The blob was in fact a string of thousands of tiny eggs laid by a little-known species of squid.

"The species that has been published is Thysanoteuthis rhombus (aka the 'diamond squid'), but it's hard to know for sure," Helm told Live Science. "ID'ing squid eggs is a pretty esoteric art."

Diamond squid can grow to be about 3 feet long, weigh up to 66 lbs. (30 kilograms) and resemble a pinkish kite attached to a cluster of tentacles. The creatures can lay between 24,100 and 43,800 eggs at a time, all encased in a gelatinous tube that can grow up to 6 feet (1.8 m) long, according to Helm. The tube's pinkish glow comes from the color of the eggs themselves, Helm said, though it's not clear what makes the hue so vibrant. [Read all about the rare squid egg blob that took the web by storm.]

"Kleptopredator" sea slug with a vicious way of feeding

Imagine you are a tiny coral polyp, and you have just finished a delicious meal of microscopic zooplankton. You sit back to digest when — Gulp! — some jerk sea slug gobbles you, and your plankton feast, right up. Rude.

The bottom-dwelling sea slug known as Cratena peregrina was known to dine on polyps, but researchers determined this year that the slug strongly prefers to chow on polyps that have just finished eating dinner. This sort of behavior is known as kleptopredation — stealing a predator's feast by swallowing up the predator and its prey at the same time — and, according to a study published Nov. 1 in the journal Biology, was observed in nature for the first time ever this year. Kleptopredation provides C. peregrina with enough plankton to account for about half of its diet, the study found, overturning previous claims that polyps were the slug's primary food source.

Not all monsters look monstrous; some just have monstrous manners. [Read all about the kleptopredation phenomenon.]

Rare, deep-ocean shark with 300 "frilled" teeth

Some deep-sea fishers were trawling near Portugal this November when they accidentally hauled up a dinosaur of a catch. Scientists aboard a nearby research vessel identified the strange catch as Chlamydoselachus anguineus — also known as the frilled-tooth shark, a species that has changed so little over the past 80 million years that researchers call it a "living fossil."

How did the frill-toothed shark get its name? Look into its spooky maw, if you dare, and behold its 300 three-pointed teeth, which resemble rows of very sharp, terrifying frills. The creatures stretch more than 5 feet long and use their impressive chompers to take down prey, which includes fish, squid and other sharks. Though the captured shark died, it still provided researchers an exciting opportunity to study it. Frilled-tooth sharks are rarely seen, as they can swim as deep as 4,600 feet (1,400 m) below the ocean's surface — deeper than most fishing vessels dare venture. [Read all about the frilled-tooth shark's unusual mating habits.]

5,000-lb. bone-filled fish

The world's heaviest bony fish was caught off the coast of Japan in 1996, weighing in at a staggering 5,070 lbs. (2,300 kg). For decades, scientists erroneously thought the whopper was a species of sunfish called Mola mola. Now, according to a paper published Dec. 5 in the journal Ichthyological Research, the big catch has been properly classified as Mola alexandrini, a species previously unknown to science.

Sunfish, in general, are the heaviest fish in the sea, with skeletons made of bone. (This differs from sharks and rays, for example, whose skeletons are made of cartilage.) Their bodies are huge and round, are shaped like wagon wheels or pancakes and can grow to be more than 10 feet long. Because of their great girth, sunfish are notoriously hard to transport and study. But genetic tests carried out earlier this year helped scientists determine that there are far more species of sunfish than previously thought — including the record-setting M. alexandrini. [Read more about the marine heavyweight's unexpected discovery.]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.