The 10 Biggest Archaeology Discoveries of 2017

Digging up the past

Archaeologists were digging up plenty of fascinating bones and other ancient remains throughout 2017, revealing more intriguing information about humans' past. From hundreds of mysterious stone structures in Saudi Arabia called gates, to a previously undiscovered cave that held Dead Sea Scrolls, to a woman who was literally buried with her husband's heart, Live Science takes a look at 10 of the coolest archaeological and historical finds of the year.

Mysterious gates in Saudi Arabia

This fall, archaeologists reported the discovery of about 400 rectangular stone structures, called gates because they resemble field gates, in Saudi Arabia. The longest of these structures is about 1,700 feet (518 meters) long — longer than four NFL football fields back to back. A few of the gates were found on the sides of lava domes. After the news of the discovery was reported on Live Science, the government of Saudi Arabia invited the archaeologists to take low-flying aerial photographs of the gates and other archaeological sites. The images the archaeologists took were . [Read more about the mysterious stone structures in Saudi Arabia.]

New Dead Sea Scrolls cave

In February, archaeologists reported that they had discovered a cave that once contained Dead Sea Scrolls near the site of Qumran, in the West Bank. Most of the scrolls that the cave once held had been plundered decades ago, although a blank scroll was found. The archaeologists said that this was the 12th cave found near Qumran that held Dead Sea Scrolls. Archaeologists are searching the desert near Qumran, and it's possible that they will uncover a 13th cave in 2018. The Dead Sea Scrolls were written around 2,000 years ago and include some of the earliest known copies of the Hebrew Bible. [Read the full story on the new Dead Sea Scrolls.]

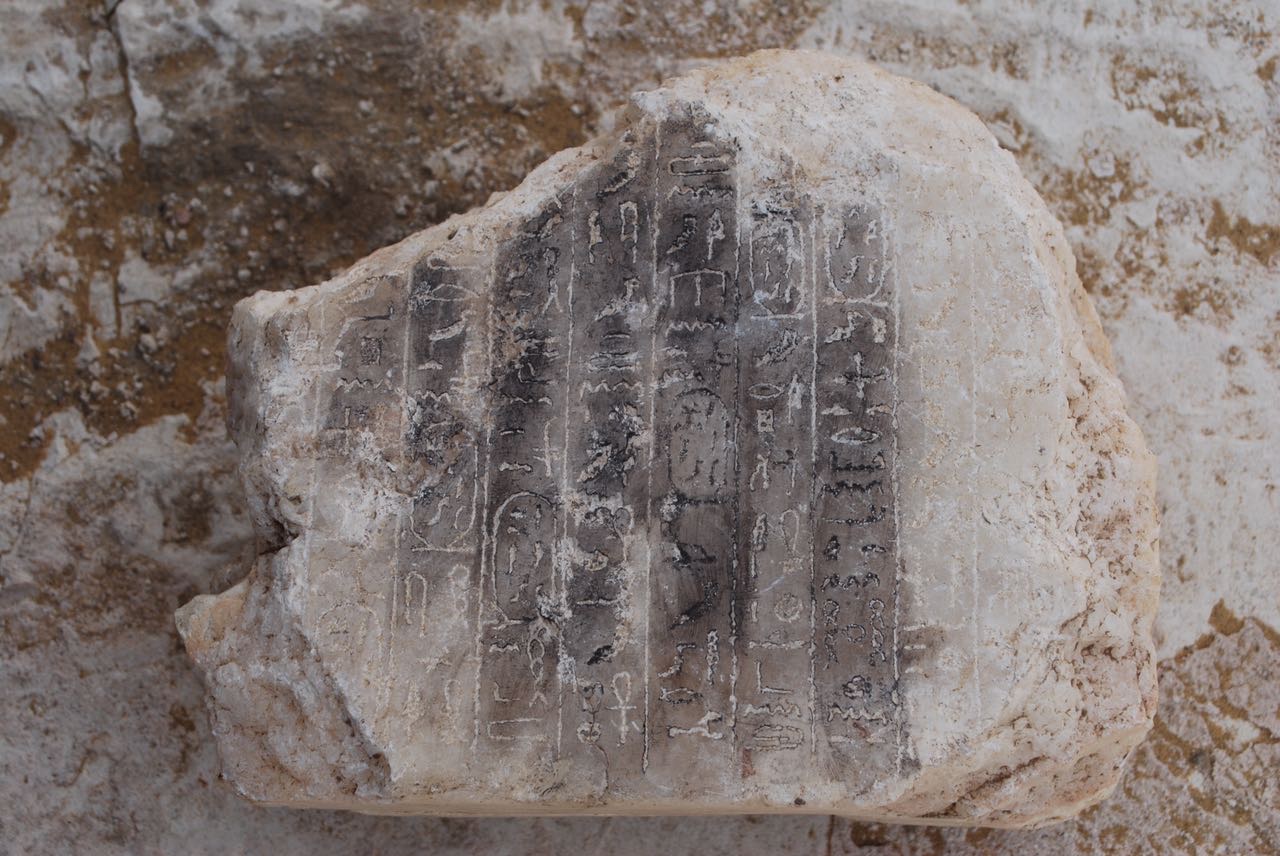

Pyramid for a princess?

Archaeologists in Egypt discovered a 3,800-year-old pyramid that bears the name of the pharaoh Ameny Qemau. Curiously, it is the second pyramid known to bear his name; the first was found in 1957, just 2,000 feet (about 600 meters) from the newly discovered pyramid. A wooden box found in the burial chamber of the newly discovered pyramid bears the name of the pharaoh's daughter, Hatshepset, who had the same name as Egypt's famous female pharaoh. One of Ameny Qemau's predecessors may have built the pyramid, and Ameny Qemau may have taken the pyramid over, put his own name on it and used it to bury his own daughter, Egyptologists said. [Read more about the princess pyramid.]

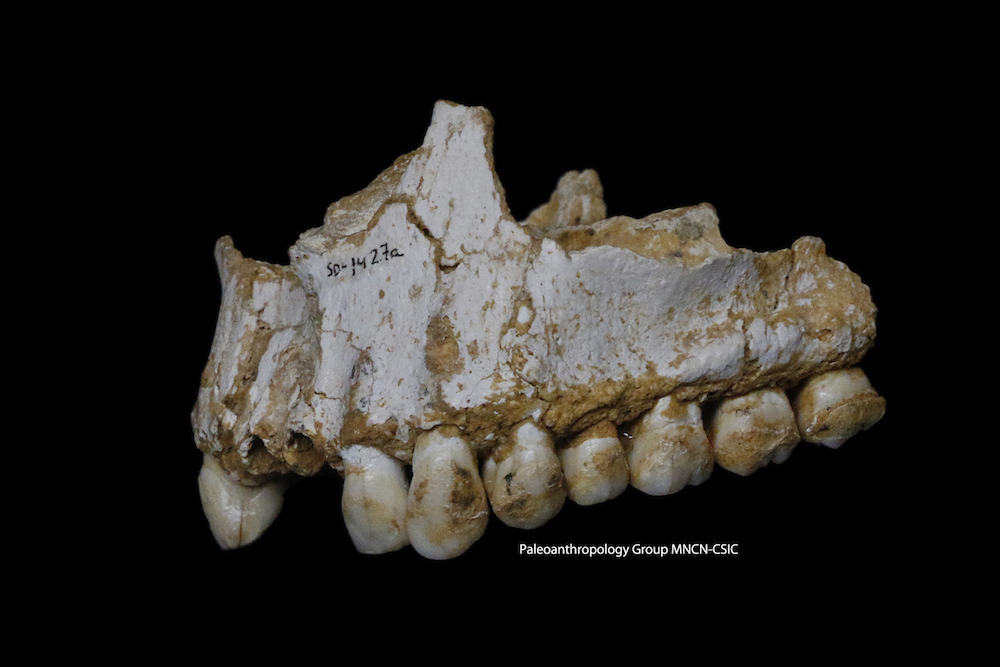

Oldest Homo sapiens skeletons

The oldest known skeletons of Homo sapiens were identified a cave in Morocco, scientists reported in research published this year. Consisting of three adults, one teenager and one child, they date back around 300,000 years and thus push the origins of Homo sapiens back by about 100,000 years, the researchers said. The findings also suggest that H. sapiens may have originated throughout the entire African continent rather than just East Africa. The scientists said the five individuals looked similar to modern-day humans. [Read the story on the discovery of the oldest known Homo sapiens skeletons.]

Ultimate romantic gesture

In what might be considered the ultimate romantic gesture, a woman named Louise de Quengo, who died in 1656 at age 65, was buried with her husband's heart literally on top of her coffin, archaeologists found. Her husband, Toussaint de Perrien, had died seven years before she did and was a patron of religious orders in Brittany, France. His heart had been cut out of his body and placed in a protective case, which, in turn, was placed on his wife's coffin.

She was buried in a convent in Rennes, France, and her husband was buried 125 miles (201 kilometers) away. Archaeologists found that de Quengo's body had also been cut into and that her heart had been removed. Presumably, her heart was also put in a protective case and placed on top of her husband's coffin, although her heart has not been found. [Read more about the embalmed heart discovery.]

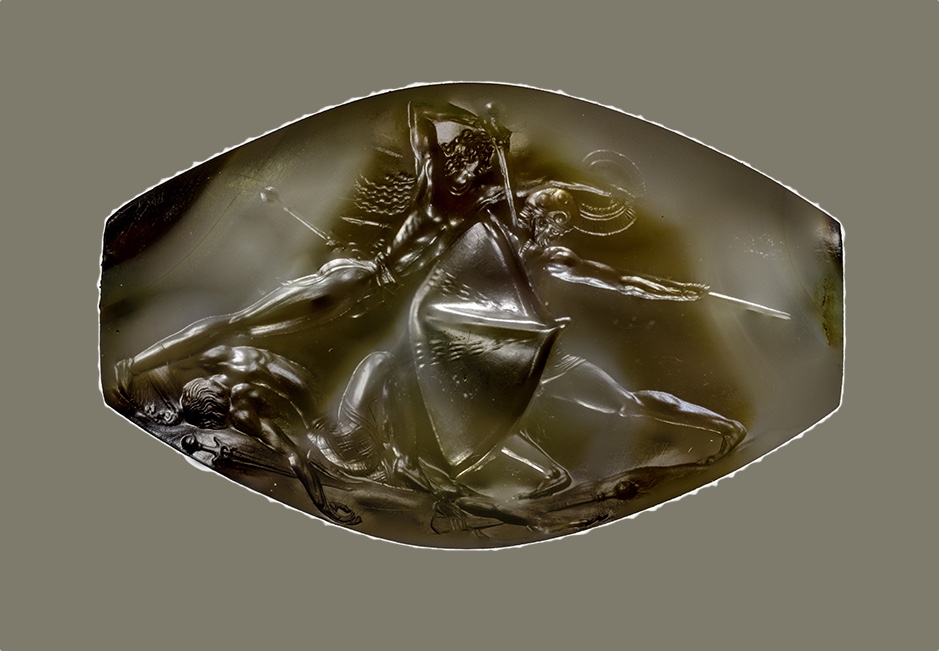

Incredible gemstone

This 3,500-year-old gemstone shows a warrior standing over a slain enemy while plunging a sword into another warrior's neck. It was buried in a tomb of a warrior in Pylos, Greece, along with about 3,000 objects. The details on the gemstone are so intricate that it takes a microscope to see all of them. While the tomb itself was first found in 2015, it has taken time to excavate, clean and analyze all of the artifacts, and the discovery of this particular treasure was announced in 2017. [Read more about the incredibly detailed Greek gemstone.]

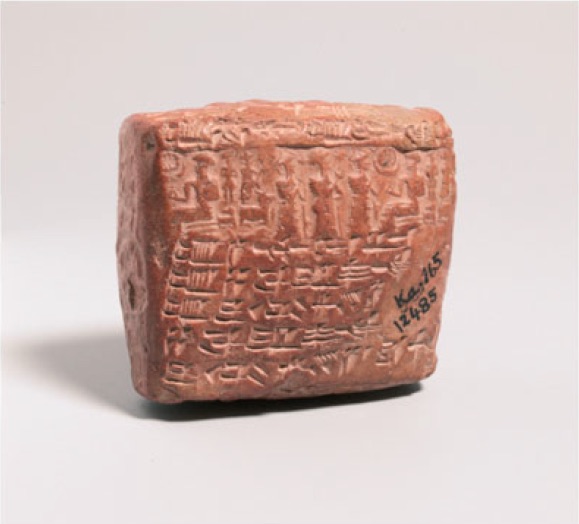

Ancient prenup

This 4,000-year-old tablet reveals what may be the earliest known prenuptial agreement between a wife and her husband. Written in Assyrian, the contract stipulates that if the wife, Hatala, does not give birth to a child within two years of marriage, then she will buy her husband, Laqipum, a female slave who will produce a child for the couple. The contract also states that if Laqipum divorces Hatala, he must pay her five mina (a unit of weight) of silver, and if Hatala divorces Laqipum, she must pay him five mina of silver. [Read more about the ancient prenuptial agreement.]

Earliest evidence of winemaking

People were fermenting wine 8,000 years ago in what is now the Republic of Georgia (located in the Caucasus), archaeologists reported this year. They found the jars used in winemaking at two sites in Georgia, now called Gadachrili Gora and Shulaveris Gora. The researchers performed chemical analyses on shards from eight large jars found at those two sites and found that the objects contained tartaric acid, a compound in grapes and wine. Previously, the oldest known evidence for winemaking was from Iran and dated back about 7,000 years. Archaeologists said the new discovery indicates that humans started making wine not long after pottery was invented. [Read more about the earliest evidence of winemaking.]

Neanderthal medical knowledge

DNA analysis of dental calculus from five Neanderthal skeletons revealed that Neanderthals possessed considerable medical knowledge and even used antibiotics, researchers reported this year. One of the Neanderthals had a dental abscess (a painful tooth infection) and a diarrhea-causing intestinal parasite but treated these conditions by consuming a type of mold that acts as a natural antibiotic. This individual also apparently took poplar, which contains ingredients used in aspirin.

"The use of antibiotics would be very surprising, as this is more than 40,000 years before we developed penicillin," study researcher Alan Cooper, director of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at the University of Adelaide in Australia, said in a statement describing the findings. The study also revealed that Neanderthal diets varied and could include more meat or more vegetables, depending on the individual. [Read more about Neanderthals' antibiotic use.]

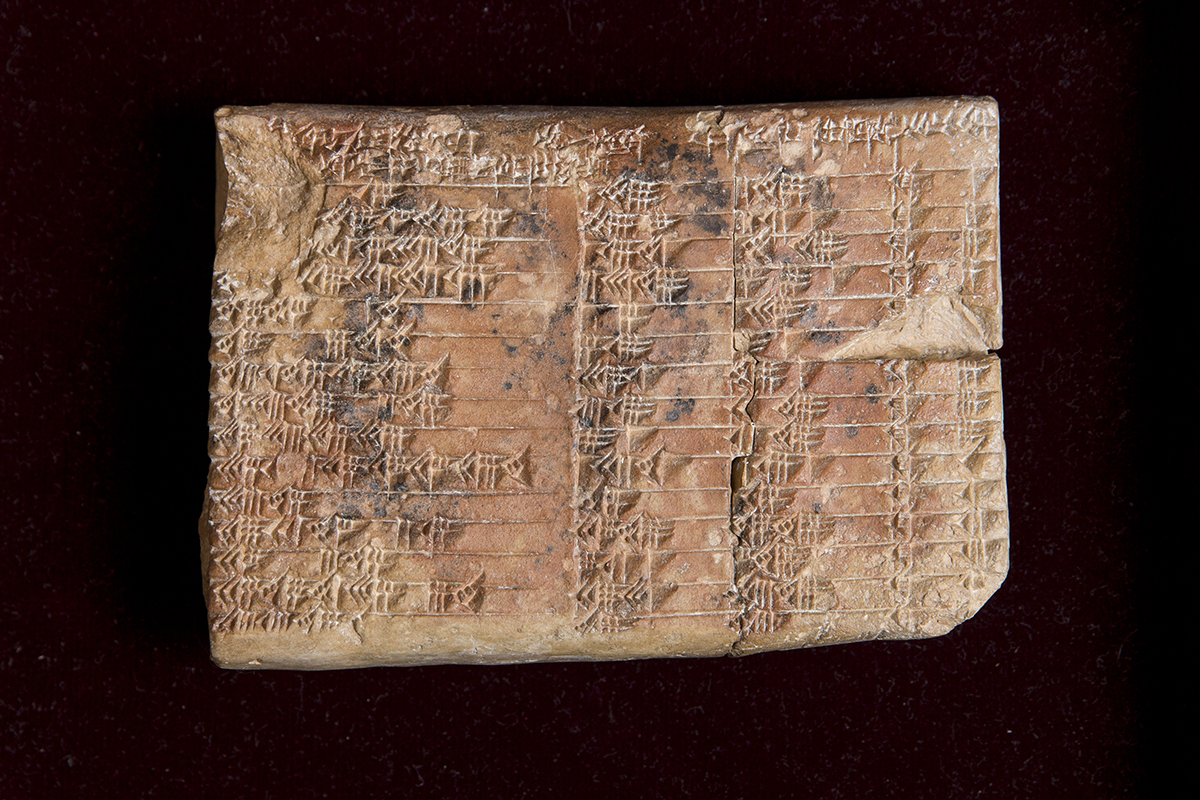

Oldest evidence of trigonometry

A 3,700-year-old tablet reveals that the Babylonians, not the Greeks, were the first to study trigonometry, the mathematics of triangles. The tablet has descriptions of 15 right triangles, the angles of inclination decreasing for each triangle the researchers found. These descriptions form part of a trigonometric table that made the study of trigonometry remarkably simple. Researchers were impressed by the simplicity of the tablet and said that modern-day math teachers may want to consider using a similar approach when teaching trigonometry.

The discovery "opens up new possibilities not just for modern mathematics research, but also for mathematics education," said study co-author Norman Wildberger, an associate professor in the School of Mathematics and Statistics at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. "The mathematical world is only waking up to the fact that this ancient but very sophisticated mathematical culture has much to teach us."

The Babylonians may have used their knowledge of trigonometry to construct palaces and pyramid-shaped structures called ziggurats, the researchers said. [Read more about this Babylonian tablet.]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.