10 Times Earth Revealed Its Weirdness in 2017

Astonishing Earth

For thousands of years, people have been studying planet Earth, and yet it continues to astonish us. Apart from being our home, Earth is the only world that we know of that supports any form of life. Its atmosphere and geology are dynamic and ever-changing. It has abundant liquid water, breathable air, and myriad ecosystems, some of which are lethal to all but the specially-adapted organisms that inhabit them.

In many ways, Earth's composition, structure and processes are understood and familiar. But there is still much about it that we are learning for the first time, and over the past year, scientists discovered many new and exciting secrets about our weird and wonderful planet.

Here are some of the most unexpected and unusual things we learned about Earth in 2017.

Hum a few bars

You can't hear it, but Earth “hums." It produces a perpetual, low-frequency drone, caused by the vibrations of ongoing, subtle microseismic movements that are not earthquakes and are too small to be detected without special equipment.

While scientists already knew about this persistent hum, they recently measured it from the ocean floor for the first time. Researchers traveled to the Indian Ocean, and over 11 months they captured the sound of the planetary vibration, known as "free oscillation." They found recurring peaks that occurred at several frequencies between 2.9 and 4.5 millihertz — about 10,000 times lower than the human hearing threshold, which is 20 hertz.

Hot rock "blob"

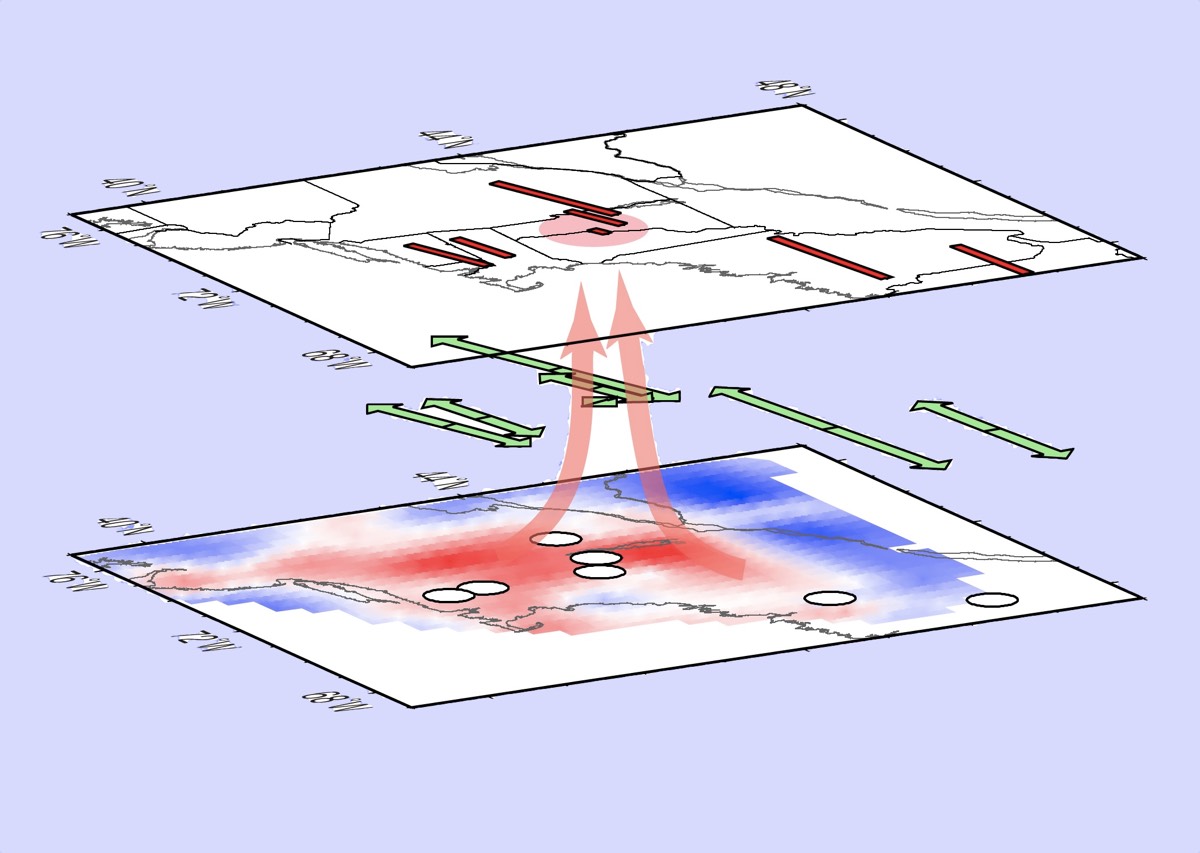

From a geological perspective, not much has changed in the continental rock of North America's eastern coast for about 200 million years — other than normal wear caused by erosion from wind, water and glacial movements.

But when scientists peered beneath the continent's rocky layers in a special project that deployed thousands of seismic detectors, they discovered something entirely unexpected under an area in the northeastern coast of the United States – a "blob" of rising, molten rock in Earth's upper mantle, located about 121 miles (195 kilometers) below the surface.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While it is unknown what caused the hot blob — or if the formation of such structures is common under continents and oceans — its small size and high temperature led scientists to estimate that it formed relatively recently, and is likely tens of millions of years old.

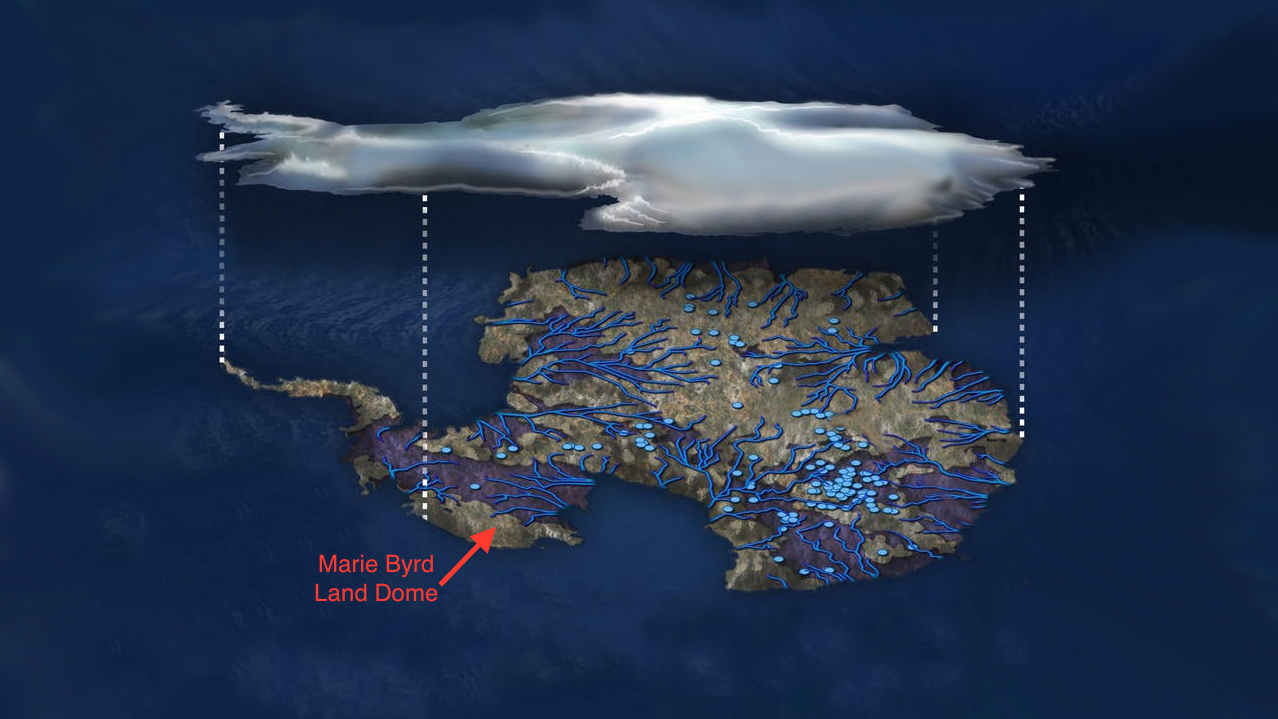

Magma plume

About 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) under Antarctica's frozen surface, the icy continent hides a red-hot secret — a column of magma, pushing toward the surface.

A dome-shaped bulge in the crust under West Antarctica's Marie Byrd Land hinted that something might be brewing under the ice sheet. Scientists built a computer model to analyze the melting and freezing of ice in the region over time, using data gathered by NASA satellites. They discovered a magma plume estimated to be as much as 110 million years old, shooting 150 milliwatts per square meter (or about 11 square feet) of heat up to the surface.

100 secret volcanoes

Under the West Antarctic Rift System in Antarctica lie 138 volcanoes that were recently mapped in a remote survey, and 91 of them were new to scientists.

The researcher who led the investigation became intrigued with Antarctica's volcanic history during his undergraduate studies. For the investigation, he and his colleagues used satellite data, aerial surveys, and radar data that peered deep below Antarctica's surface ice, identifying 91 locations with evidence of volcanic rock, a signature of volcanic activity from known volcanoes in that region.

Though it is not yet known how many of the hidden volcanoes are still active, prior studies show that Antarctica was overall more volcanically active in the past, during Earth's warmer periods. As arctic ice thins due to climate change, volcanoes that have been long inactive may awaken from their slumber, the scientists said in a statement.

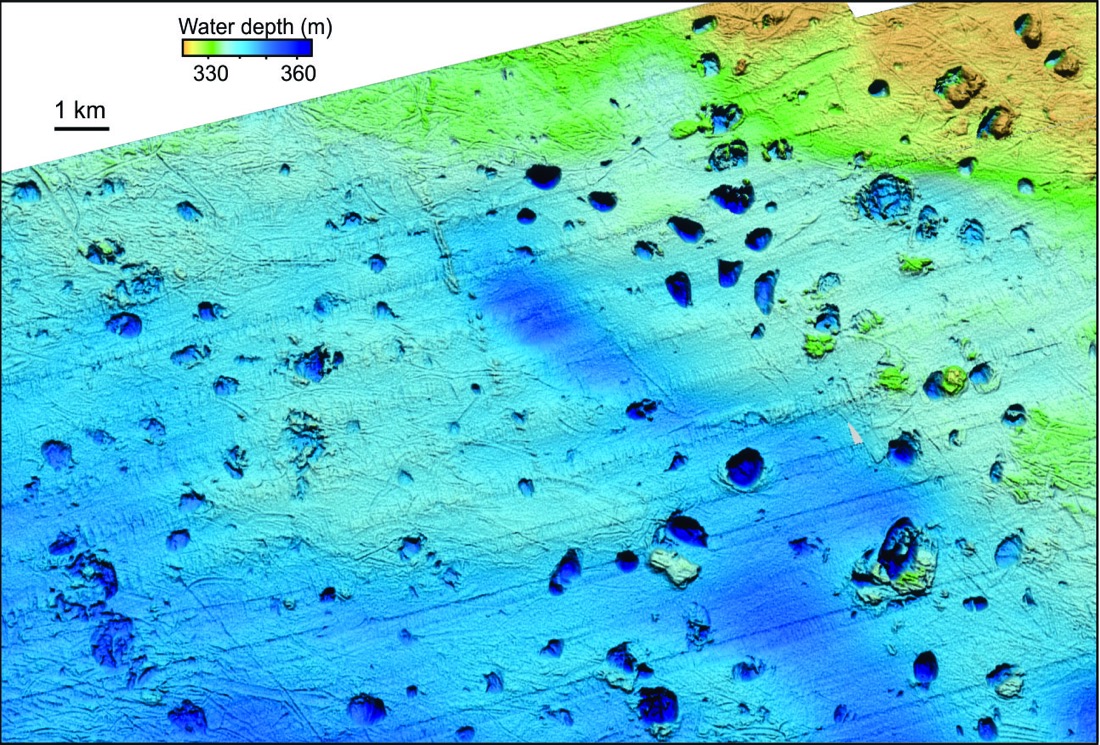

Ancient underwater eruptions

Over 11,000 years ago, massive eruptions of frozen methane gas under the Arctic seafloor created enormous craters as wide as 12 city blocks, according to scientists who recently mapped the craters in detail for the first time.

They found that there were many more craters than previously suspected, with thousands of smaller pits alongside more than 100 of the biggest ones, likely formed as retreating ice sheets destabilized reservoirs of frozen gas.

Studying these craters could help scientists better understand the role that methane might play in our warming world, and could assist in the prediction of similar disruptive events under Antarctica's ice sheets, according to the researchers.

Massive undersea landslide

Researchers creating a 3D map of the seafloor near a section of Australia's Great Barrier Reef discovered evidence of an enormous undersea landslide that took place around 300,000 years ago, tumbling vast amounts of rocky debris down the reef and generating a tsunami that towered about 90 feet (27 meters) high.

Sonar scans of the reef revealed eight towering structures on the seafloor of the Queensland Trough — an area that was expected to be flat — hinting to the scientists that they had been deposited by a cataclysmic event that caused a massive disruption in the sediment.

The amount of rubble produced by the landslide was estimated at about 7.6 cubic miles (32 cubic kilometers), a volume about 12,000 times that of the Great Pyramid of Giza, and the landslide was likely triggered by a powerful earthquake.

Primeval reservoirs

Rocky specks from Earth's infancy are carried by lava flows that originate in dense reservoirs under the planet's crust, scientists discovered. These primordial particles date to 4.5 billion years ago, when Earth formed as a series of smaller rocky bodies colliding in the newborn solar system.

Decades earlier, researchers had detected ratios between helium isotopes in certain lava samples that did not correspond with expected ratios in the rock around it. Rather, that ratio's closer analogue was older planetary "building blocks," dating to Earth's formation, about 50 million years after the youthful plane took shape, the study authors explained.

They traveled around the world to sample 38 volcanic hotspots, and discovered that only the highest-temperature lava flows contained this unusual helium ratio, suggesting that these hottest hotspots were drawing their lava from the mantle's most buoyant plumes, which were able to draw lava from dense reservoirs lying at the boundary between Earth's mantle and core, where primeval rocky particles have survived for billions of years.

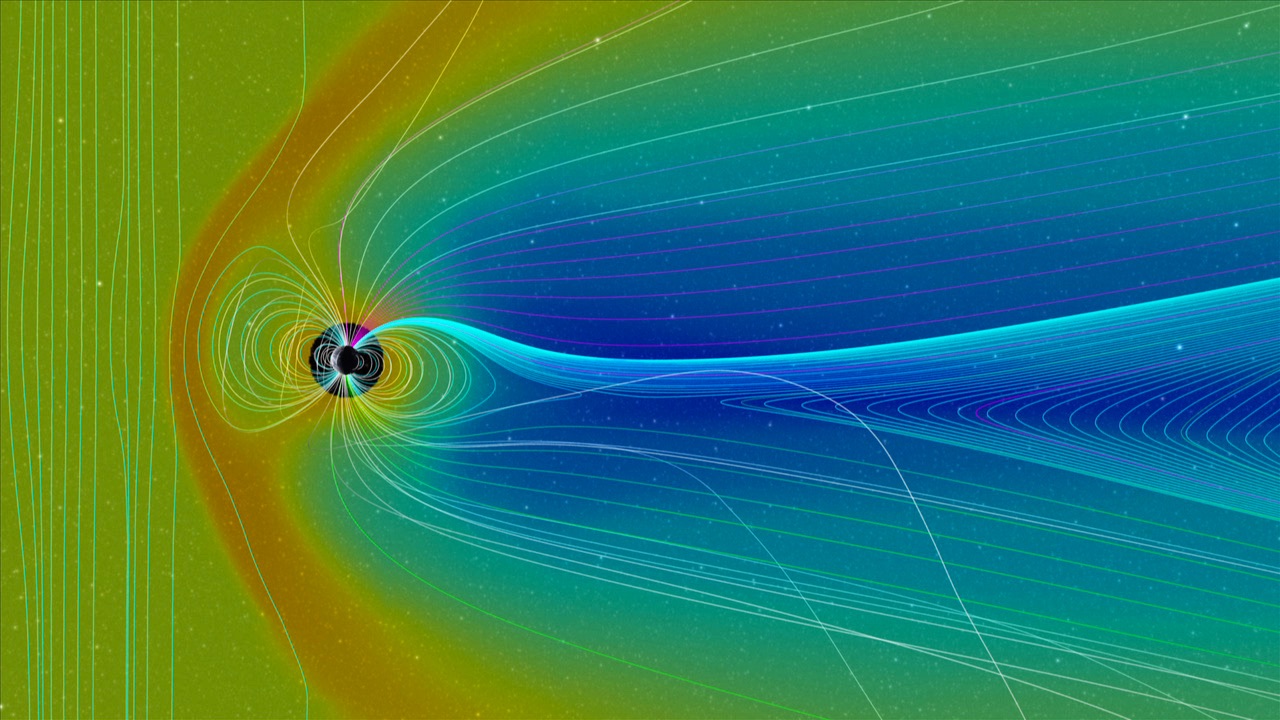

Ancient geomagnetic field spike

Pottery that was fired thousands of years ago in the Middle East's ancient kingdom of Judah — a region encompassing what is now Syria, Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon and other nearby areas — retains evidence of an impressive spike in Earth's geomagnetic field.

By baking the clay to make jugs, the people of Judah sealed hints about the geomagnetic field into the clay's minerals. Meanwhile, dates that were stamped into the pottery enabled researchers to link geomagnetic fluctuations to specific time periods.

They learned that 2,500 years ago, during the late eighth century B.C., Earth's geomagnetic field was briefly 2.5 times stronger than it is currently. Evidence of other significant fluctuations suggested that not only could intense magnetic field changes take place, but also that they could wax and wane far more quickly than previously suspected.

The "eighth continent"

New Zealand, New Caledonia, and several other nearby islands dotting the Pacific Ocean are actually the visible tips of a mostly-submerged eighth continent, according to geologists.

Dubbed Zealandia, the continent is estimated to be about 1.8 million square miles (4.9 million square kilometers), slightly larger than India.

Zealandia emerged about 85 million years ago after the breakup of the supercontinent Gondwana. As Gondwana fractured, the land mass now identified as Zealandia "got stretched," according to researchers. The stretching thinned out the newborn continent's crust and caused it to sink.

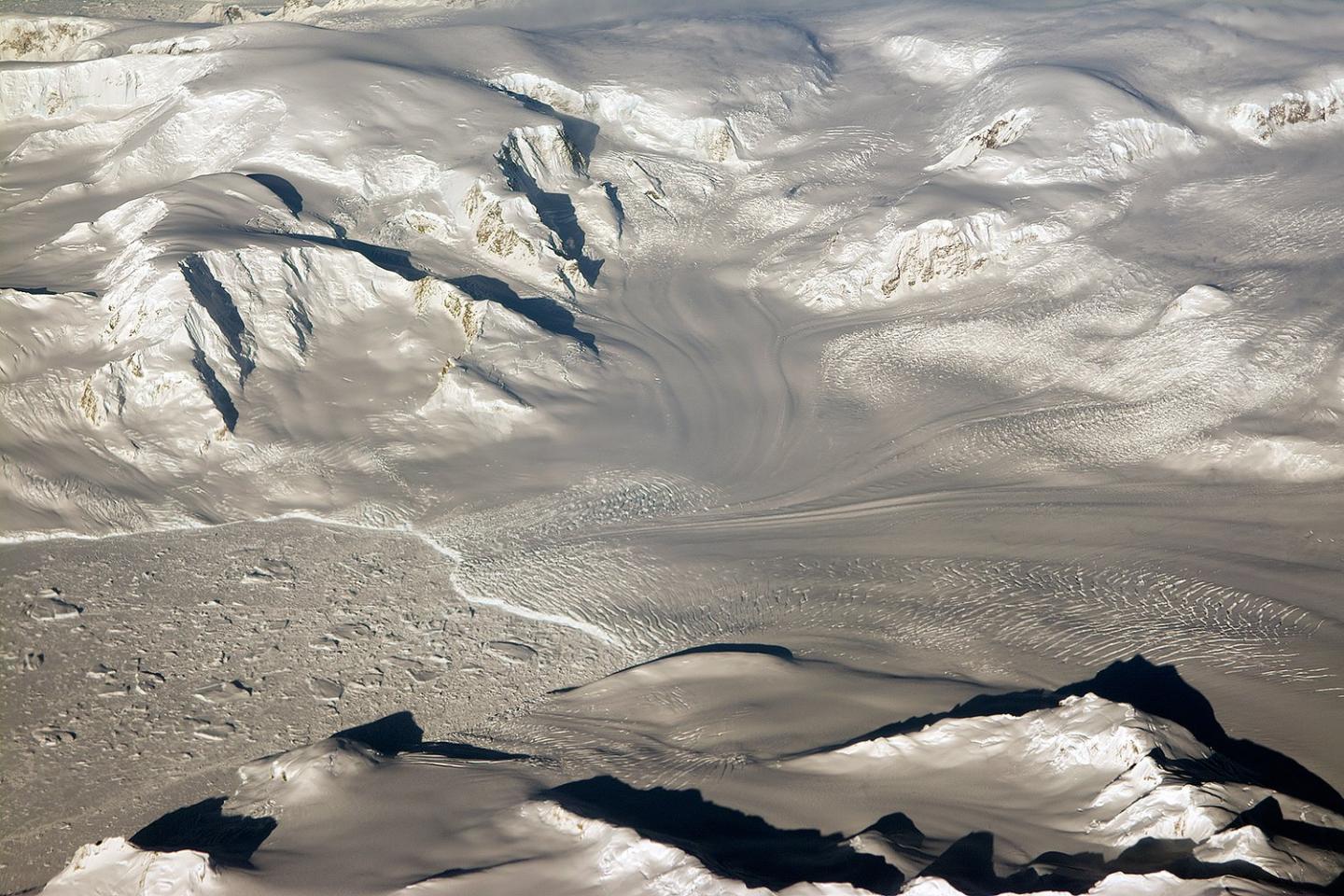

Huge under-ice valleys

Recently, scientists mapped a network of enormous valleys running below Antarctica's glacial sheets. The valleys channel warm ocean water under the frozen continent's glaciers and melt away ice from below, accelerating the glaciers' retreat.

The depths of the valleys far exceeded previous estimates, surprising scientists. Valleys underneath the Crosson and Dotson ice shelves originated at 3,930 feet (1,200 meters) below the ice, sloping upward to terminate about 1,640 feet (500 m) beneath Crosson and approximately 2,460 feet (750 m) beneath Dotson.

Researchers discovered the valleys by analyzing Antarctica's topography, taking measurements of ice motion, and incorporating data from NASA's Operation IceBridge mission, which monitors sea ice, glaciers and ice sheets from the air.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.