Common Ancestor of Sharks and Humans Lived 440 Million Years Ago

Humans and sharks are incredibly different creatures, but the two shared a common ancestor 440 million years ago, a new study finds.

Researchers made the discovery by studying the fossilized bones of a shark that lived during the Devonian, a period lasting from 416 million to 358 million years ago, when four-legged animals first started colonizing land.

By studying the remains of this 385-million-year-old shark, scientists were able to deduce that sharks and the ancestors of humans split before the Devonian, during the Silurian period (443 million to 416 million years ago), a time when the first fungi and arthropods, including arachnids and centipedes, moved onto land. [7 Unanswered Questions About Sharks]

Ancient shark

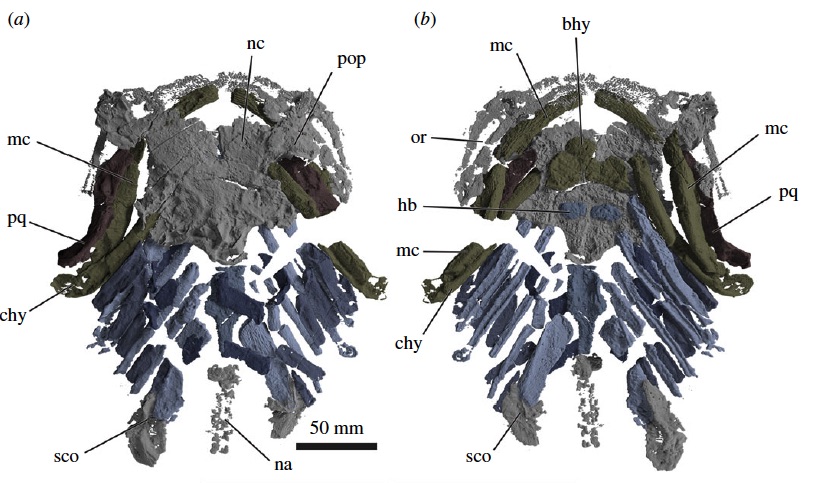

Researchers initially described the shark, known as Gladbachus adentatus, in 2001, naming it after Bergisch Gladbach, the German city where it was found. Its species name reflected its seemingly toothless jaws, although the new analysis revealed that it did have teeth during its lifetime, said study lead researcher Michael Coates, a professor in the Department of Organismal Biology and Anatomy at the University of Chicago.

Even though researchers had already described G. adentatus, Coates and his colleagues decided to take another look at the shark fossil, largely because of its old age, unusual anatomy and completeness. "Fossil sharks are usually preserved as a mess of tiny scales and teeth and not much else," Coates told Live Science in an email.

In contrast, G. adentatus had an articulated skeleton, meaning that its bones were still in place. Coates compared the shark's remains to roadkill — the 2.6-foot-long (80 centimeters) shark was "squashed flat," he said.

Even so, the remains are remarkable, Coates said. They indicate that the shark had a wide mouth and splayed-out gills. "The body is preserved as a sheet of prickly scales," Coates said. "The skeleton of the head has a very course grain to it, almost like the pattern of tree bark."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ancient relations

G. adentatus is one of the earliest known fossil sharks on record. After analyzing it with a high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scan, the researchers found that the animal "represents the tip of a branch, a side-shoot, from the base of the shark family tree," Coates said. "As such, [it] reveals new information about the diversity of early sharks that we haven't had access to before."

These features suggest that other, even older fossils of isolated scales do, in fact, come from early sharks. This discovery helped the researchers make the new estimate that at least 440 million years have passed since humans and sharks shared a common ancestor, Coates said.

Furthermore, shark evolution had many branches, they found. "Several lineages of the earliest sharks converged on what we now recognize as classic shark-like features, such as having a long throat with multiple gill slits," Coates said.

Scientists used to think that multiple gill slits were primitive, but G. adentatus shows they aren't, he said. "These serial gill slits represent an early specialization, and, we argue, this specialization is for filter feeding, somewhat like a modern basking shark," Coates noted. [Aahhhhh! 5 Scary Shark Myths Busted]

What's more, despite its initial name, G. adentatus actually had several kinds of teeth, including small mono-, bi- and tri-cuspid teeth lining its jaw, the researchers wrote in the study.

The study was published online yesterday (Jan. 2) in the journal Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.