The First Americans: Ancient DNA Rewrites Settlement Story

A genetic analysis of a baby's remains dating back 11,500 years suggests that a previously unknown human population was among the first to settle in the Americas.

Scientists recovered the DNA from an infant — only a few weeks old when she died — buried at the Upward Sun River archaeological site in the interior of Alaska. Their data indicated that the baby belonged to a group of people who were genetically distinct from humans in northeastern Asia, the region that launched a migration into North America over a now-submerged land bridge across the Bering Strait.

However, the data also showed that this group differed genetically from the two known branches of ancestral Native Americans. The unexpected discovery of this Alaskan population offers a new perspective on the first people to settle in the Americas and presents a more detailed view of their migratory path, researchers explained in a new study. [In Photos: Human Skeleton Sheds Light on First Americans]

Life and death in the Americas

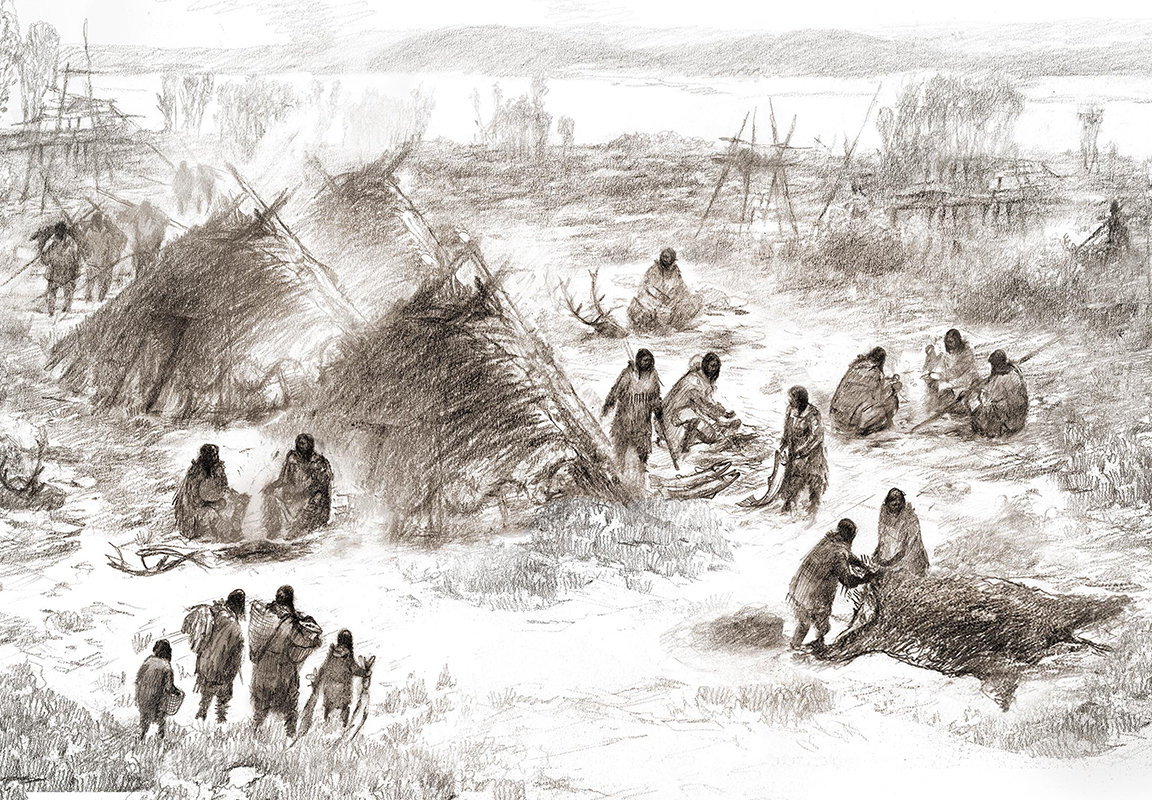

Many thousands of years ago, the site where the infant lived — albeit briefly — and died was a residential camp with three tent-like structures. The baby, a girl, was buried beneath one of them, along with another female infant who was likely stillborn; later, a third child, who was about 3 years old when he or she died, was cremated in a hearth at the same spot, study co-author Ben Potter, a professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, told Live Science.

A burial deep in a pit below the frozen surface helped to preserve the infant's remains — along with viable samples of the baby's DNA and partial DNA from the younger infant. The two were named Xach'itee'aanenh t'eede gaay ("sunrise child-girl") and Yełkaanenh t'eede gaay ("dawn twilight child-girl") by the local indigenous community, according to the study. The researchers worked closely with native representatives while recovering and examining the remains and the rest of the archaeological site, Potter said.

The remains of ice age humans are exceptionally scarce. Populations were highly mobile foragers; people generally didn't settle together in permanent villages or create burial grounds, and finding a site where someone had died and was buried was typically a matter of luck, Potter explained.

"It's really rare to encounter hunter-gatherer burials — period," he told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Another issue is that we're dealing with some of the earliest people in the Americas, and so there's an even smaller population to deal with. All of these factors make it difficult to find these [remains], so these are really rare and priceless windows into the past," he said.

Reconstructing an ancient journey

Previous explanations of humans' arrival in the Americas suggested that about 15,000 years ago, during the latter part of the icy Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), people crossed Beringia — the Bering land bridge — in a single migratory wave, then dispersed to North America and later to South America. More-recent findings showed that founding populations of Native Americans diverged genetically from their Asian ancestors about 25,000 years ago, introducing the idea that humans settled in Beringia for 10,000 years before reaching North America.

This newfound Alaskan group — now dubbed ancient Beringians — appeared about 20,000 years ago, while the Native American ancestral branches showed up between 17,000 and 14,000 years ago, the study authors reported.

The new DNA data — among the oldest genomic material from ice age humans to date — bolsters the notion of an extended stay in Beringia. But the surprising discovery of the previously unknown population in Alaska, which has its own distinct genetic makeup, adds a new twist to the human migration story, suggesting two scenarios for the transition from Beringia into the New World, Potter said.

The most likely possibility is that the genetic "split" between the ancient Beringians and ancestral Native Americans occurred in Eurasia, with the groups arriving independently in North America, the study said. The populations arrived either at the same time through different geographic areas or one after the other following the same general route, according to the study.

"This scenario is most consistent with the archaeological record, which to date lacks secure evidence of human occupation in Beringia and the Americas" dating to more than 20,000 years ago, the scientists wrote.

But it is also possible that the split occurred after a single population was established in eastern Beringia, the researchers added. [In Images; Ancient Beasts of the Arctic]

Adaptable and persistent

The far north was one of the last places on Earth to be populated by modern humans, a species that evolved in Africa. And there is much to be learned by examining how our species migrated and then adapted along the way to survive and thrive in vastly different ecosystems — particularly in the north, where this group of ancient Beringians persisted from 12,000 to 6,000 years ago, weathering dramatic environmental shifts along the way, such as climate change, large extinctions of animal species and the emergence of evergreen forests, Potter told Live Science.

And the Beringians managed to do it without significantly changing their technology, centered on a unique type of stone tool called a microblade, he said. This tool was commonly seen in ancient hunter-gatherer societies in Asia but was not found anywhere else in North or South America, Potter said.

"Understanding the adaptive strategies that made that possible — the innovations, the social organization, how people cooperated and how they made their tools — is really a profound way to understand our species," Potter said.

The findings were published online today (Jan. 3) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.