Bombogenesis: What's a 'Bomb Cyclone'?

"Bomb cyclones" or "weather bombs" are wicked winter storms that can rival the strength of hurricanes and are so called because of the process that creates them: bombogenesis.

It's a mouthful of a meteorology term that refers to a storm (generally a non-tropical one) that intensifies very rapidly.

Bomb cyclones tend to happen more in the winter months and can carry hurricane-force winds and cause coastal flooding and heavy snow.

How bombogenesis works

The word bombogenesis comes from combining "bomb" and "cyclogenesis," or meteorology speak for storm formation. Technically speaking, a storm undergoes bombogenesis when it's central low pressure drops at least 24 millibars in 24 hours, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). (A millibar is a unit of pressure that essentially measures the weight of the atmosphere overhead. Typical sea-level pressure is about 1,010 millibars.)

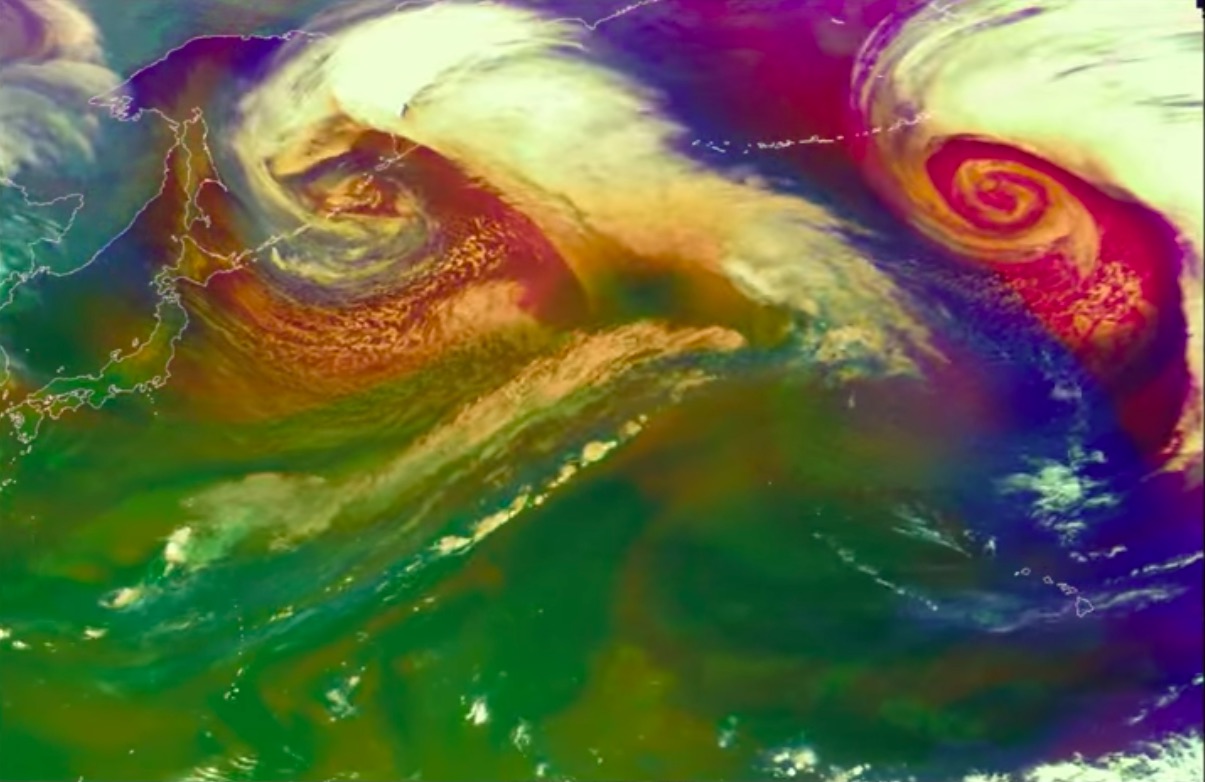

Storms occur when a rising column of air leaves an area of low pressure at the Earth's surface, which in turn sucks in the air from surrounding areas. As that air converges, the storm starts to spin faster and faster, like a twirling ice skater who pulls in her arms, which leads to higher wind speeds. The closer you are to the center of the storm, the stronger the winds.

If a storm is strong enough or deepens (drops in pressure) rapidly enough, its winds can reach hurricane-force, or 74 mph (119 km/h) or higher. Of the 43 North Atlantic storms that achieved hurricane-force winds during the winter of 2013-2014, 30 underwent bombogenesis, according to NOAA.

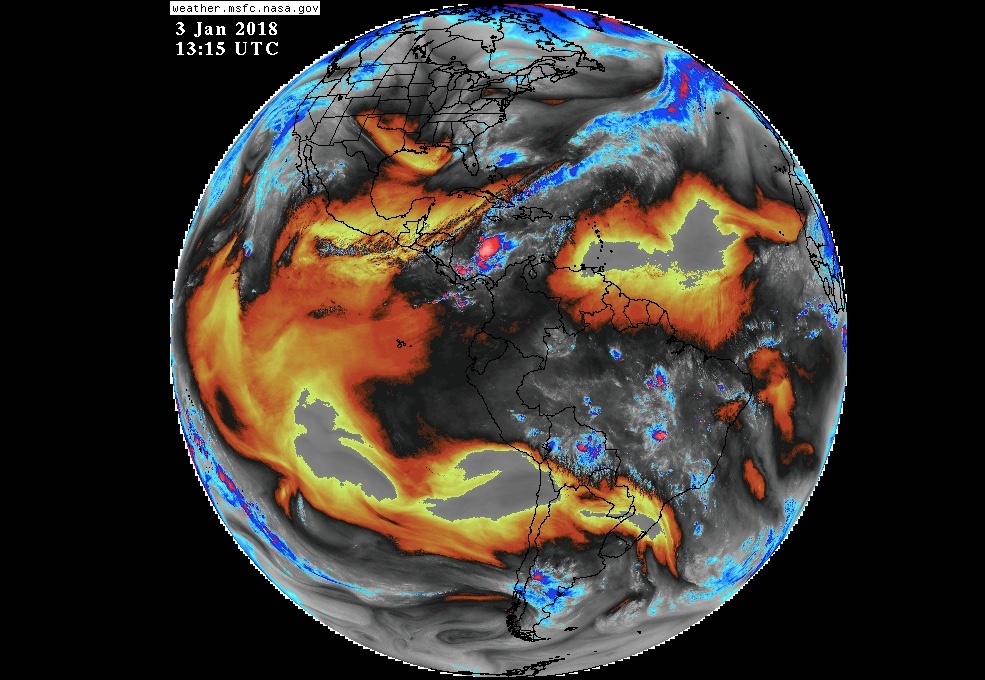

Bombogenesis tends to occur when a strong jet stream high in the atmosphere interacts with an existing low-pressure system near a warm ocean current like the Gulf Stream. The jet stream pulls air out of the storm's rising column of air, causing the surface low to deepen.

When and where bombogenesis occurs

Bombogenesis tends to occur more often in winter in what are called mid-latitude (or extra-tropical) cyclones. These storms are driven by the collision of warm and cold air masses, whereas as tropical cyclones are driven by convection, or the transfer of heat upward (though they can also undergo rapid intensification and sometimes the term bombogenesis is used to describe that process as well).

The western North Atlantic is one of the prime areas for bombogenesis since cold air over North America collides with warm air over the warmer ocean water (which holds onto heat for longer than land does) in the colder months, giving rise to nor'easters (so-called because the winds along the coast are blowing from the northeast), according to the Washington Post's Capital Weather Gang. The moisture from the ocean combined with the cold air can lead to heavy snows.

Bombogenesis is also common in the northwest and southwest Pacific and the South Atlantic. Weather bombs seem to be more common in the Northern Hemisphere than in the Southern Hemisphere.

Notable weather bombs

The 1993 Superstorm (also called the Storm of the Century), which dumped record amounts of snow across parts of the eastern United States from March 12-13 of that year, was a particularly impactful bomb cyclone, Accuweather reported. The storm's pressure dropped 33 millibars in 24 hours

A storm that bombed out over the Great Lakes in November 1913, dubbed the White Hurricane, sank at least 12 ships and killed at least 250 people.

A February 2017 snowstorm that hit the Northeast led to blizzard conditions and snowfall rates up to 4 inches (10 centimeters) per hour in some places, according to NOAA.

Hurricane Charley in 2004 is a good tropical example. The hurricane, which hit southwest Florida as a Category 4 hurricane, dropped 23 millibars in pressure in less than 5 hours, the National Weather Service said.

Original article on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.