Silk Road Travelers' Ancient Knowledge May Have Irrigated Desert

More than 1,700 years ago, ancient farmers in China transformed one of Earth's driest deserts into farmland, possibly by using ancient knowledge of irrigation passed along by Silk Road travelers, a new study finds.

Archaeologists made the finding by using satellite imagery to analyze the barren foothills of northwestern China's Tian Shan Mountains. These peaks form the northern border of China's vast Taklamakan Desert and are part of a chain of mountain ranges that have long hosted prehistoric Silk Road routes connecting China with lands to its west.

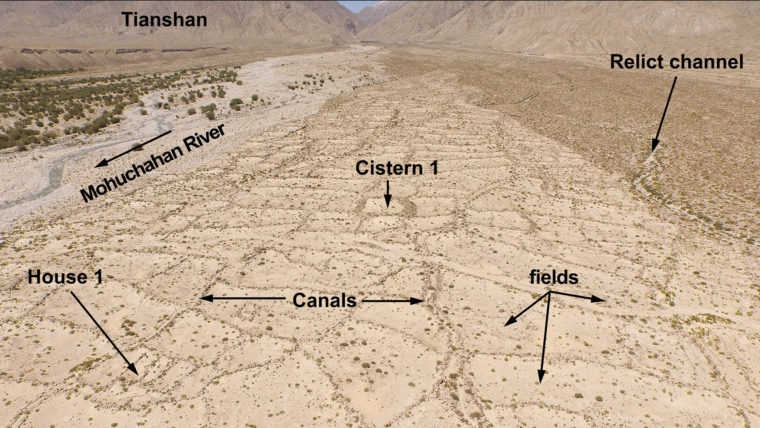

The satellite imagery of one particularly dry area caught the researchers' attention: a region dubbed Mohuchahangoukou, or MGK, which gets a seasonal trickle of snowmelt and rainfall from the Mohuchahan River. From the ground, the area looks like little more than a scattering of boulders and ruts, but when the researchers flew a commercial four-rotor "quadcopter" drone about 100 feet (30 meters) over MGK to capture images, they could see outlines of dams, cisterns and irrigation canals feeding a patchwork of small farm fields, the scientists said. [The 10 Driest Places on Earth]

Initial excavations at the site confirmed the presence of farmhouses and graves that radiocarbon dating and other methods suggest likely date back to the third or fourth century A.D., the scientists noted. This ancient farming community was likely built by local herding groups that sought to add crops such as millet, barley, wheat and perhaps grapes to their diet, the researchers added.

"It was very surprising to me that a site of this size was not discovered earlier by scientists, who have been studying this area for 100 years," study author Yuqi Li, an archaeologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told Live Science.

By feeding river water into farms, this ancient, well-preserved irrigation system helped people grow crops in one of the world's driest climates. The area at the edge of the Taklamakan Desert historically receives less than 3 inches (6.6 centimeters) of rainfall annually, or about one-fifth of the water typically deemed necessary to cultivate even the most drought-tolerant strains of wheat and millet, the researchers said. The area is drier than the Kalahari in southern Africa, the Gobi Desert in Central Asia and the American Southwest, but not as dry as the Atacama Desert in Chile or the Sahara Desert in northern Africa, Li said.

These new findings could help resolve a long-standing debate over how irrigation techniques first made their way to this arid corner of northwestern China's Xinjiang region. While some researchers suggest that all major irrigation techniques were brought to Xinjiang by troops of China's Han dynasty, which lasted from about 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, these new findings support the idea that local communities may have practiced arid-climate irrigation techniques before the Han.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The most likely scenario is that this irrigation technology came from the West," Li said.

Prior work suggested that so-called agropastoral communities, which practiced both farming and herding along mountain ranges in ancient Central Asia, may have spread crops throughout a region that scientists call the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor. This giant exchange network may have spanned much of the Eurasian continent, bringing ancient nomadic groups together as they moved herds to seasonal pastures, and perhaps spreading irrigation techniques as well. [In Photos: Ancient Silk Road Cemetery Contains Carvings of Mythical Creatures]

The researchers noted that irrigation systems similar to MGK's have also been found at the Geokysur river delta oasis in southeast Turkmenistan dating to about 3000 B.C. and further west at the Tepe Gaz Tavila settlement in Iran dating to about 5000 B.C. The researchers added that an irrigation system nearly identical to MGK's is seen at the Wadi Faynan farming community, which was established in a desert environment in southern Jordan during the latter part of the Bronze Age (2500 B.C. to 900 B.C.) and includes boulder-constructed canals, cisterns and field boundaries.

In contrast, known Han-dynasty irrigation systems in Xinjiang are larger than ones seen in MGK. For instance, while MGK's system irrigates about 500 acres across seven parcels, the systems introduced by the Han dynasty in the Xinjiang communities of Milan and Loulan used wider, deeper, straight-line channels up to about 5.3 miles (8.5 kilometers) long to irrigate much larger areas. One irrigated more than 12,000 acres (4,800 hectares).

"The sophistication of the system at MGK surprised me," Li said. "Previously, I thought agropastoralists there randomly grew some crops to supplement their diets, but we've found an elaborate system [that they used] to assist in their agriculture. It's very likely they had a very sustainable system to develop agriculture in a desert environment, probably more sustainable than those constructed by Han dynasty troops."

Much remains for scientists to discover in Xinjiang, Li said. "The drone very cost-effectively allows me to survey a big area with very little investment of time and energy," he noted.

Li and his colleagues detailed their findings in the December issue of the journal Archaeological Research in Asia.

Original article on Live Science.