Little 'Rainbow' Dinosaur Discovered by Farmer in China

Despite its fearsome, Velociraptor-like skull, a 161-million-year-old dinosaur the size of a duck would have been a shining, shimmering and splendid sight to behold — mostly because it sported gleaming, iridescent feathers that were rainbow-colored, a new study finds.

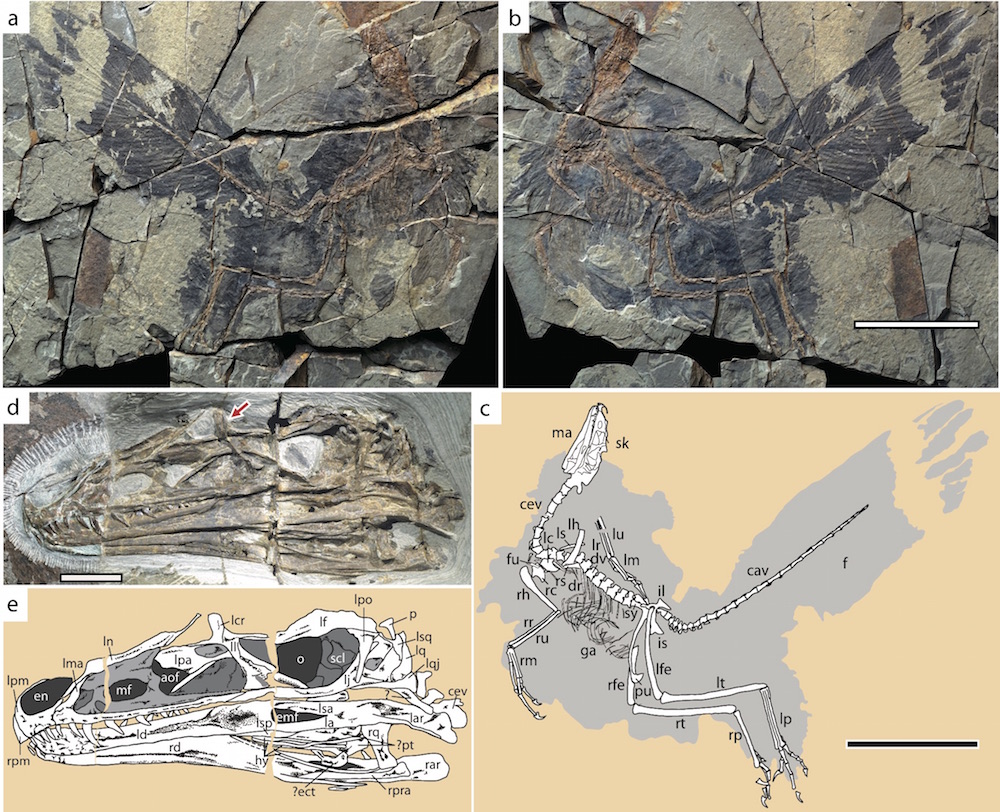

Iridescent feathers glistened on the dinosaur's head, wings and tail, according to an analysis of the shape and structure of the creature's melanosomes, the parts of cells that contain pigment.

"The preservation of this dinosaur is incredible — we were really excited when we realized the level of detail we were able to see on the feathers," study co-researcher Chad Eliason, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field Museum in Chicago, said in a statement. [See images and illustrations of the iridescent dinosaur]

A farmer in northeastern China's Hebei Province discovered the fossil, and the Paleontological Museum of Liaoning in China acquired the find in 2014. After discovering its iridescence and noting the unique bony crest on top of the dinosaur's head, researchers gave it a colorful name — Caihong juji — which is Mandarin for "rainbow with the big crest."

Dazzling discovery

The scientists discovered the dinosaur's iridescence and colorful nature by examining its feathers using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Incredibly, the SEM analysis showed imprints of melanosomes in the fossil. The organic pigment once contained in the melanosomes is long gone, but the structure of the cell parts revealed the feathers' original colors, the researchers said. That's because differently shaped melanosomes reflect light in different ways.

"Hummingbirds have bright, iridescent feathers, but if you took a hummingbird feather and smashed it into tiny pieces, you'd only see black dust," Eliason said. "The pigment in the feathers is black, but the shapes of the melanosomes that produce that pigment are what make the colors in hummingbird feathers that we see."

The pancake-shaped melanosomes in C. juji matched those in hummingbirds, indicating that the Jurassic-age dinosaur had iridescent feathers, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

C. juji isn't the first dinosaur on record to have iridescent feathers; Microraptor, a four-winged dinosaur also sported gleaming feathers, Live Science previously reported. But that dinosaur lived about 40 million years after C. juji, so the newly identified dinosaur is by far the oldest dinosaur on record to flaunt iridescent plumage, the researchers said.

C. juji is also the oldest animal on record to have asymmetrical feathers, which help modern birds steer while flying. However, unlike modern birds, whose asymmetrical feathers are on their wing tips, C. juji sported these lopsided feathers on its tail. That, combined with the fact that C. juji likely couldn't fly, led the researchers to conclude the dinosaur likely used its feathers to attract mates and keep warm.

This "bizarre" feature has never been seen before in either dinosaurs or birds, which evolved from dinosaurs, said study co-researcher Xing Xu, a researcher at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. This suggests that tail feathers may have played a role in early, controlled flight, Xu said.

But not all of C. juji's features are out of the blue. Some of its traits, such as its bony head crest, resemble those on other dinosaurs, researchers said.

"This combination of traits is rather unusual," study co-researcher Julia Clarke, a professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Texas at Austin, said in the statement. "It has a Velociraptor-type skull on the body of this very avian, fully feathered, fluffy kind of form." [Tiny Dino: Reconstructing Microraptor's Black Feathers]

This mixture of old and new traits is an example of mosaic evolution, when some parts of an animal evolve, but others stay the same, the researchers said.

The study was published online today (Jan. 15) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.