What's Hiding Inside Egypt's Great Pyramid? Tiny Robots May Find Out

Using cosmic particles called muons, and possibly tiny robots, scientists hope to figure out what created two mysterious voids inside the Great Pyramid.

Possibilities range from a new burial chamber to a sealed-off construction passage.

Built by the pharaoh Khufu (whose reign started around 2551 B.C.), the Great Pyramid of Giza stands 455 feet (138 meters) tall and was the tallest human-made structure in the world until the Lincoln Cathedral was completed in England in the 14th century.

Scientists with the Scan Pyramids project reportedthe discovery of two previously unknown voids in the Great Pyramid in an article published in November 2017 in the journal Nature. The larger of the two voids is at least 98 feet (30 m) long and is located above a giant passageway known as the grand gallery that leads to Khufu's burial chamber. The smaller void is located behind the north face of the pyramid and consists of a corridor whose length is unclear. Muon detectors and thermal imaging were used to make these discoveries. [In Photos: Looking Inside the Great Pyramid of Giza]

Next phase

Scientists plan to conduct more muon testing in the Great Pyramid; and they are developing robots that may be able to enter the smaller void and peer inside using a high-resolution camera.

Currently, the scientists know little more about the larger void than its length. "There is a big difference if the [larger] void is horizontal or if it is inclined," said Mehdi Tayoubi, the president and co-founder of the Heritage Innovation Preservation Institute, one of the institutions involved with the Scan Pyramids project. If the larger void is inclined, for instance, it could be a large passageway like the grand gallery, Tayoubi explained. On the other hand, if the void is horizontal, then it could consist of one or more chambers. Additionally, it's possible that the smaller void, which scientists already know consists of a corridor, could have linked up to the larger void in ancient times, Tayoubi said. [Photos: Amazing Discoveries at Egypt's Giza Pyramids]

To gather this information, the researchers will set up muon detectors in spots in the Great Pyramid that have yet to be investigated, including a series of so-called relieving chambers, which are located near the larger void. The relieving chambers are located above the king's chamber — a chamber that holds a sarcophagus that many archaeologists believe was used to bury Khufu. These chambers may have been constructed to take pressure off the ceiling of the king's chamber, preventing the ceiling from collapsing (hence, their name).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Robot research

While the new muon tests are being carried out, another team, led by Jean-Baptiste Mouret, a senior researcher at Inria, the French National Institute for Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, is constructing two robots that may be able to peer inside the smaller void.

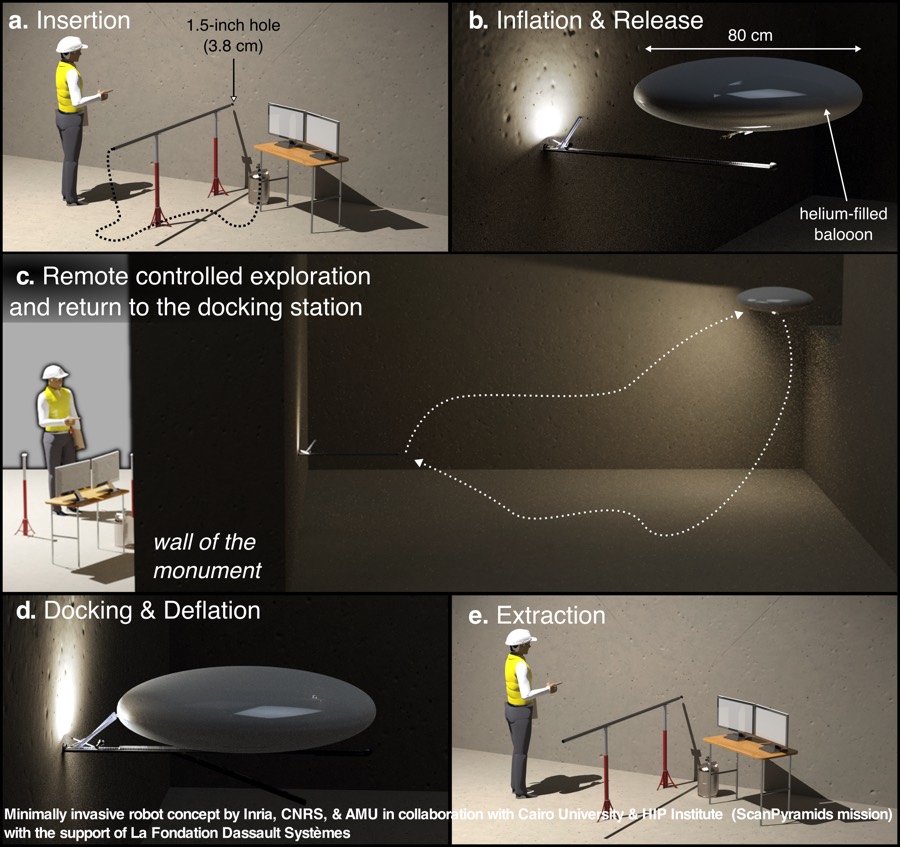

Mouret said that the team would drill a hole about 1.5 inches (3.8 centimeters) across and then insert the little robots through it and into the void.

"First, we want to send a 'scout robot,' which is basically a pan-tilt camera with a lot of lights fitted in a tube-like robot," Mouret told Live Science. "The goal is to survey what is on the other side of the wall and get high-resolution pictures."

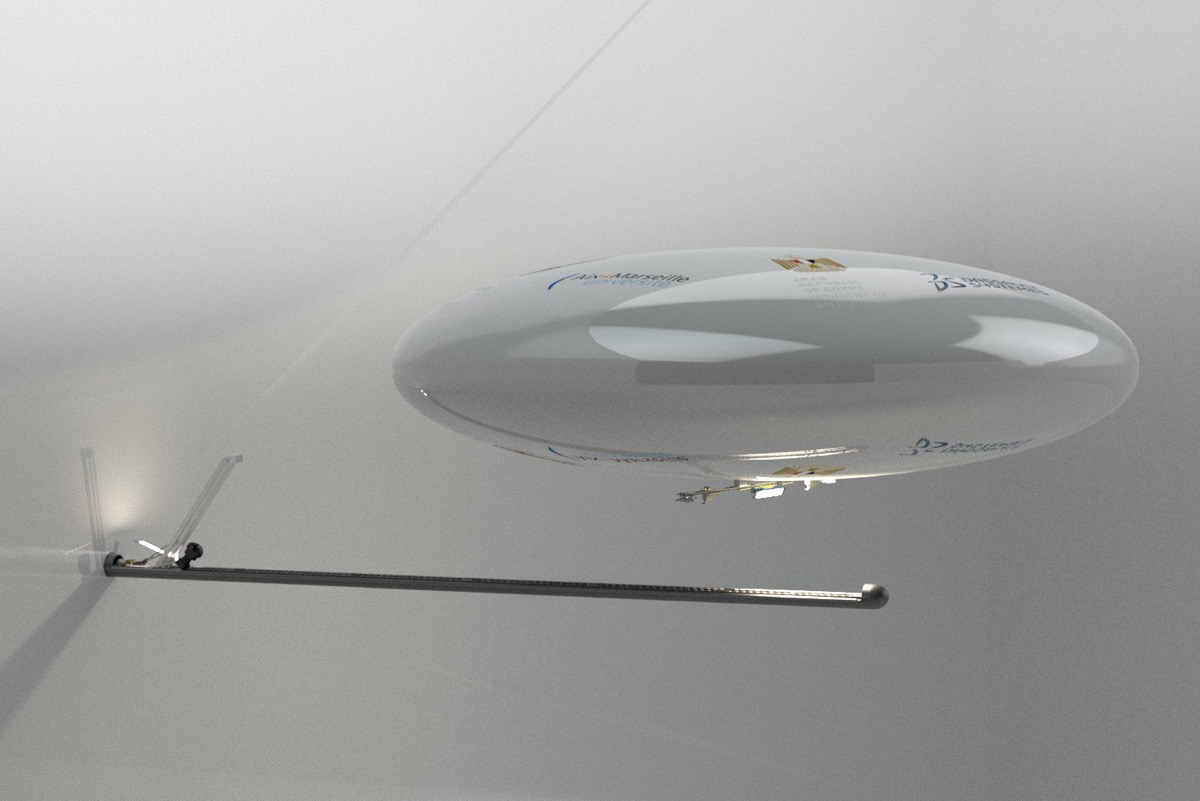

Mouret continued, "If there is something promising, then we will extract the scout robot and insert the exploration robot. For this robot, we are currently designing a flying blimp that is folded for the insertion and inflated remotely in the [the smaller void]." The blimp would allow the robot to fly around the smaller void and take pictures. The flying robot wouldn't have to navigate stairs or rocks and could move faster and take pictures from more points of view than a ground-traveling robot could, Mouret said.

They have a working prototype of both the scout and blimp robots. "However, we are still working on designing a reliable deployment and folding mechanism to deploy the blimp," Mouret said.

Before those robots can begin exploring, scientists need to gather more precise information on the dimensions and location of the smaller void, Mouret said, explaining that only then will the team know where to drill a hole. "Our hope is that our robots will be ready by the time the Scan Pyramids team figures out exactly where we need to drill," Mouret said.

The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities will also need to give final approval for the robots. The hole that needs to be drilled would damage the pyramid slightly.

"We are working hard to have a robot that is reliable as possible and as little damaging as possible; and we hope that we will be able to convince the Ministry of Antiquities that this is the most appropriate technology for the next step. In the meantime, we might deploy our robots in other places," such as heritage and industrial buildings, Mouret said.

Tayoubi emphasized that robot exploration is not the immediate goal of the Scan Pyramids project, but rather something that may be considered in the future.

Public outreach

Muon testing and analysis is a slow process and will take at least a year before the Scan Pyramids team has new results, Tayoubi said. In addition to their research, the scientists are working with documentary makers to create "Secrets of the Dead: Scanning the Pyramids." That will premiere Jan. 24, 2018, at 10 p.m. local time on PBS and can be viewed online starting Jan. 25 on PBS's website and PBS's apps.

Additional videos and information that help the public understand the team's research can also be seen on the Scan Pyramids website and a video showing how the robots may explore the smaller void can be seen on YouTube.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.