Mystery Solved: Here's What Caused a Massive Epidemic in Colonial Mexico

Researchers have cracked a nearly 500-year-old mystery about the germ that caused the so-called cocoliztlioutbreak, an epidemic that killed countless indigenous people in Mesoamerica shortly after the Spaniards arrived in the New World.

The malady wasn't smallpox, measles or another Old World disease; rather, it was likely Salmonella poisoning, the researchers concluded in a new study.

"We were successful in recovering information about a microbial infection that was circulating in this population," study co-lead researcher Alexander Herbig, a scientist in the Department of Archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (MPI-SHH), in Germany, said in a statement. [27 Devastating Infectious Diseases]

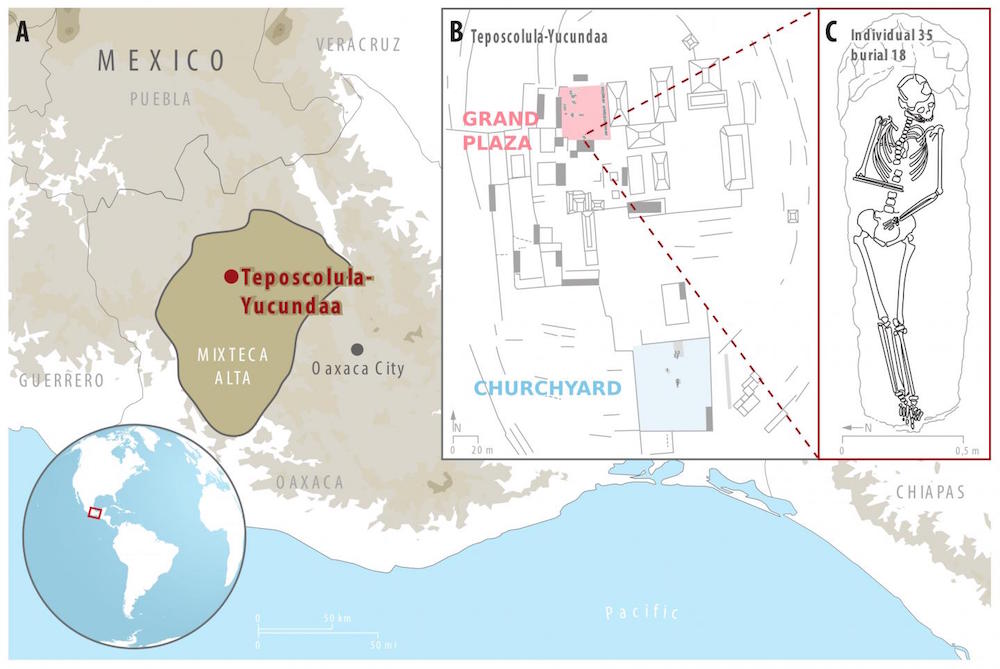

The 1545-1550 cocoliztli epidemic was immense, claiming victims in vast swaths of Mexico and Guatemala, including the Mixtec town of Teposcolula-Yucundaa, located in Oaxaca, Mexico. When the epidemic ended, the Mixtec moved their city from a mountaintop down into a valley next door, meaning their cemetery — filled with the bodies of those who succumbed to the epidemic — remained untouched for hundreds of years.

This cemetery was a scientific gold mine for researchers who were curious about the epidemic's cause. To investigate, the team of scientists who wrote the new study carefully excavated the skeletal remains of 29 people buried in the Teposcolula-Yucundaa cemetery, and then used a computational program to identify ancient bacterial DNA within the samples.

The program identified traces of the bacterium Salmonella enterica in 10 of the samples. Then, the researchers used a DNA enrichment technique to reconstruct S. enterica's entire genome. This helped the researchers conclude that the 10 people were infected with a subspecies of Salmonella known as S. paratyphi C, which causes enteric fever, a category of fever that includes typhoid.

This discovery marks the first time that scientists have found microbial evidence of an S. enterica infection from ancient, New World samples, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Enteric fever can cause high fever, dehydration and gastrointestinal problems, and is still a major health threat today. There are about 21 million cases of thyphoid and 222,000 typhoid-related deaths worldwide every year, according to a 2014 estimate reported by the World Health Organization. However, little is known about its prevalence in ancient times, the researchers noted.

The study was published online Jan. 15 in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.