Photos: 508-Million-Year-Old Bristly Worm Looked Like a Kitchen Brush

Bristly worm

The fossils of an ancient, eyeless worm show it was covered in so many bristles that it looked like a kitchen brush. The finds are helping researchers solve a mystery about the evolution of ringed worms, a group that includes the modern earthworm and leeches, a new study finds.

Curiously, this 1-inch-long (2.5 centimeters) worm had bristles around its mouth, a feature not seen in any ringed worms today. This strange characteristic suggests that the ringed worms' head evolved from another body segment that had bristles, the researchers said.[Read more about the kitchen brush-like worm]

Marble Canyon

Paleontologists excavate Kootenayscolex barbarensis from Marble Canyon Quarry. From left to right: Christopher Cameron, Joseph Moysiuk, Karma Nanglu, Jesse Chadwick and Calla Carbonne.

Fossil excavation

Researchers found the Marble Canyon site in Kootenay National Park in British Columbia, Canada, in 2012, and uncovered thousands of fossils when they returned to the site in 2014 and 2016. In this photo, Karma Nanglu (left) and Cédric Aria (right) search for fossils of Cambrian-age critters.

Karma Nanglu

Karma Nanglu is the lead author of the study on K. barbarensis.

Field crew

The crew who helped excavate the fossils of K. barbarensis, from left to right: Jesse Chadwick, Maryam Akrami, Cedric Aria, Jean-Bernard Caron (study co-author), Pierre Vincent, Linda Tsuji, Joseph Moysiuk and Karma Nanglu (study first author).

[Read more about the kitchen brush-like worm]

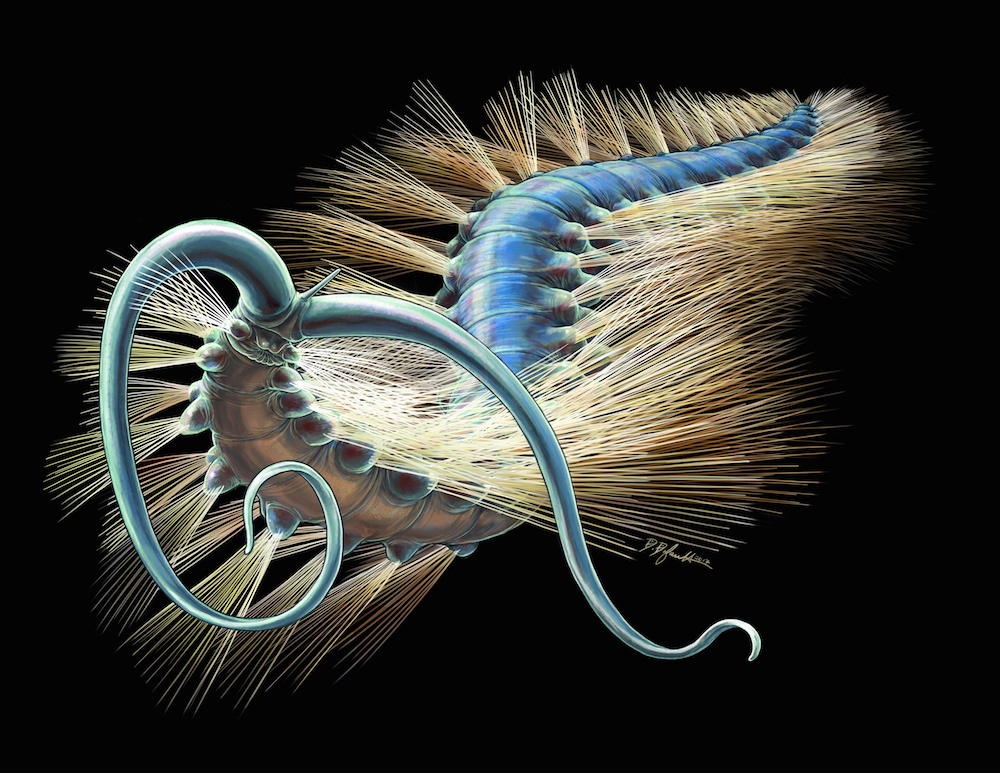

Kootenayscolex barbarensis

The Cambrian-age critter K. barbarensis is an annelid, a group known as the ringed worms. This worm had long tentacles, known as palps, on its head that helped it sense the world around it. Its body was covered with fleshy appendages known as parapodia, which hold bristles called chaetae, the researchers said.

K. barbarensis used these structures to move around.

Close up

This close-up shows that K. barbarensis had a small antenna between its tentacles. It also had parapodia and chaetae on its head, features that aren't found on modern annelids.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

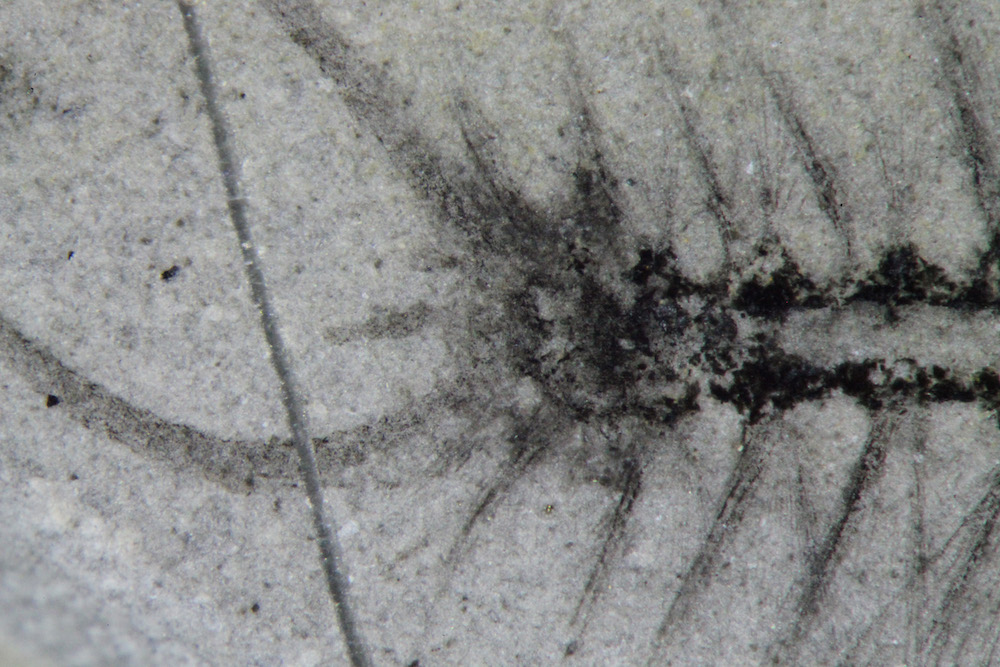

Cardiovascular tissue

Note the dark structures inside the head and parapodia of K. barbarensis. These dark splotches may be the degraded remains of neural and cardiovascular tissue, the researchers said.

A large gut (middle structure) is filled with sediment, indicating that the critter ate sea mud and filtered out the organic components it could eat.

Young and old

The adult K. barbarensis is tiny, about 1 inch (2.5 cm) long. But the juveniles are even smaller, less than 0.4 inches (1 cm) long.

"Burgess Shale fossils were created when ancient, underwater mudslides buried animals so quickly that their bodies underwent little decay," Nanglu told Live Science. "Finding the juveniles and adults together probably means that they were living in the same area when a mudslide tumbled them all together."

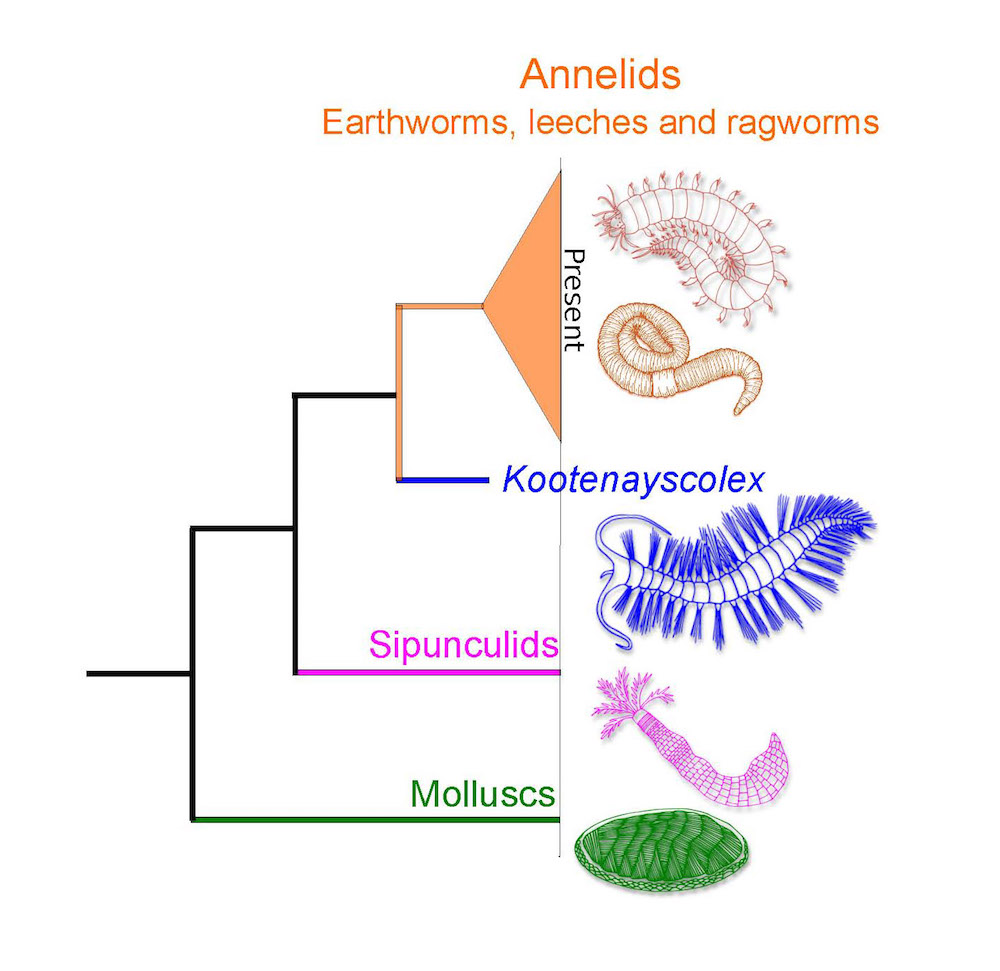

Family tree

This family tree shows how K. barbarensis fits into the annelid evolutionary tree.

[Read more about the kitchen brush-like worm]

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.