This Parasite Uses Your Own Gut Bacteria Against You

If you've ever sipped some untreated tap water while you were abroad on vacation, you may have returned home with an unexpected souvenir: diarrhea.

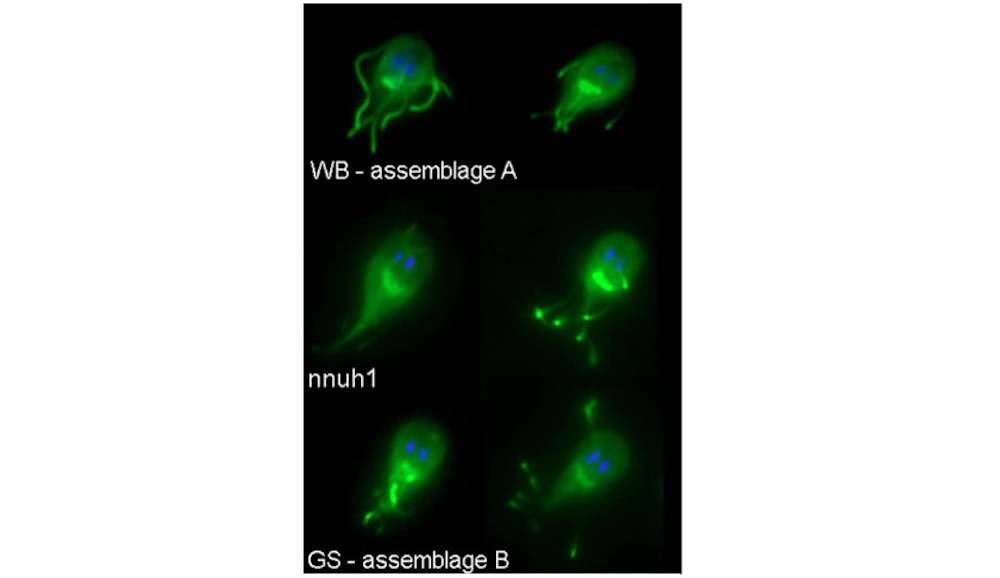

In most cases, there's a good chance you can blame a resilient, waterborne parasite called Giardia, which is responsible for one of the most common gastrointestinal illnesses in the world. Giardiasis infects an estimated 2 percent of people in high-income countries and 33 percent of people in developing countries, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Contaminated water can make its way into food, lakes and even municipal water supplies.

But despite how widespread giardiasis is, scientists are still puzzling over what the parasite does inside a host's intestines. In part, that confusion arises because the symptoms of an infection can vary greatly, from severe nausea, diarrhea and dehydration to nothing at all. [10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors]

But in a new paper published Jan. 29 in the journal GigaScience, researchers from the Norwich Medical School at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in England may have finally uncovered an answer — and it's akin to microscopic espionage. By releasing proteins that look and act just like certain human cells, Giardia parasites can stealthily cleave open a host's intestinal cells and leave them open — potentially exposing the host's GI tract to a bacterial feeding frenzy, the researchers wrote.

"We were actually surprised by the simplicity of the mechanism,"said study author Kevin Tyler, a senior lecturer at Norwich Medical School.

In their new study, Tyler and his colleagues analyzed several Giardia specimens using a mass spectrometer to identify the parasite's precise protein composition. Of the roughly 1,600 proteins the researchers saw, two particular families appeared ready-made to cut through the layers of protective mucus in the human gut.

Microscopic mimics

The first family of proteins that jumped out to the researchers are called proteases, proteins that help the human body digest other proteins, Tyler told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"However, if you put them onto a cell, they'll eat through the cell lining and cause damage," Tyler said. "So, we knew those were probably part of the story."

The second family of proteins was more surprising. "There was a large group that looked very much like human proteins we call tenascins," Tyler said. "We believe that these are structural and functional mimics that've evolved independently in the parasite to do the same things that our proteins do."

In the human body, tenascins work as part of your cellular remodeling crew. "Tenascins are part of our extracellular matrix, which is present between cells to glue them together and make tissues," Tyler said.

"Most of the proteins in the extracellular matrix are there to bind the cells together, but when you need to move cells around and remodel tissue, then you need proteins that can unstick them," he said. "That's what tenascins do: unstick cells."

Combined with proteases, these tenascin-look-alike proteins could pack a powerful one-two punch in the host's intestinal cells. "With the protease, these parasites are pulling the cells of the intestine apart in order to get nutrients from the host," Tyler said, "and with the tenascins, they're stopping the cells from coming back together. So, they've essentially made these human proteins to keep the flow of nutrients open."

And once this metaphorical refrigerator door swings open, Tyler said, there's no telling what else might come looking for a cellular snack. [Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick]

Giardiasis: Is your biome to blame?

Because Giardia colonizes the gut, any cells it slices open could become vulnerable to an unpredictable swarm of naturally-occurring gut bacteria (otherwise known as your microbiome) that might also want to feed on the sugars, lipids and amino acids seeping out between cells. Tyler and his colleagues hypothesized that this bacterial buffet — not the Giardia itself — may lead to the most severe symptoms of giardiasis.

"The majority of damage [from Giardia infection] probably comes from accompanying bacteria that can get into that environment and start to proliferate on the foodstuffs that are released between the cellular junctions," Tyler said. "Because people have different bacteria in their guts than one another, some [people] may have more bacteria that causes an inflammatory reaction, or they may have immune systems that react in a more inflammatory way. That probably is the difference between those people who experience severe symptoms and those people who don't."

The UEA researchers hope that this enhanced understanding of Giardia leads to more-effective treatments, as well as methods for differentiating the most dangerous Giardia strains from more innocuous ones, Tyler said. And now that the parasite's protein-mimicking trickery has been exposed, it may even draw back the curtain on other common parasites that could be exploiting similar infection strategies, he said.

"We don't think Giardia is alone in making use of this mechanism," Tyler said. "It's simply the first one we've noticed."

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.