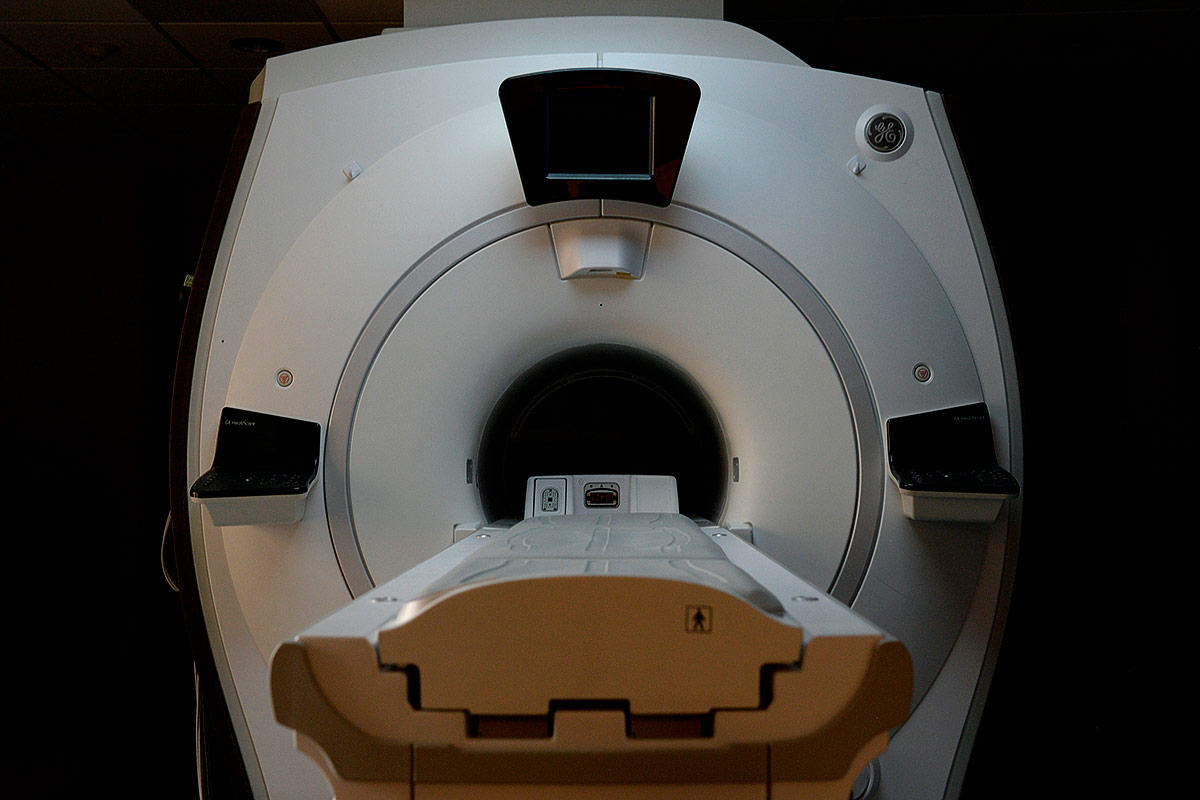

Man Dies in MRI Accident: How Does This Happen?

A man in India has reportedly died after being yanked toward a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) machine, according to news reports.

The man, Rajesh Maru, was visiting a relative at a hospital in Mumbai and had been handed a metal oxygen cylinder to carry, according to the Agence France-Presse. He entered the MRI room after being told the machine was off, but the powerful magnet that runs the machine was functioning and pulled the oxygen cylinder toward it. Maru may have died from inhaling liquid oxygen from the damaged cylinder, according to Mumbai police. The police also said two hospital staff members had been arrested for causing death by negligence. [27 Oddest Medical Cases]

MRI imaging is quite safe for human tissue, but introducing metal near the machines can be deadly. That's because the MRI machine works by using large magnets to create strong magnetic fields, 1,000 times the strength of a standard refrigerator magnet. These mega-magnetic fields align the positively charged protons within the nuclei of the hydrogen atoms in the body's soft tissue. There are a lot of hydrogen atoms in soft tissue, because soft tissue is rich in H2O, aka water. (The skin is about 64 percent H2O and the lungs are 83 percent, according to a 1945 paper in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.)

While they're lining up protons, MRI scanners also use radio waves to vary the magnetic field, forcing the protons to flip their alignment in response. After the field turns off, the protons return to their usual orientation, which produces radio signals that the MRI machine can measure. The speed at which the protons return to normal is different depending on the tissue, so the radio signals produce an image that differentiates between muscles, organs and other structures.

It's that strong magnetic field that can prove dangerous if there's any metal in the room when the machine is switched on, as the magnet will yank metal objects toward it. Patients must remove any metal from their bodies before getting scanned; anyone with certain metal implants that can't be removed (most older pacemakers, for example) can't get an MRI scan.

Occasionally, metal objects brought into the room during scans cause tragic accidents. In 2014, a technician at another hospital in Mumbai spent 4 hours wedged inside an MRI machine after he was pinned between a ward assistant carrying an oxygen cylinder and the scanner. The technician lost blood circulation below the waist and was temporarily paralyzed; he also suffered organ damage and internal bleeding, according to the Mumbai Mirror. Last year, the maker of the machine, General Electric, paid the technician a settlement of 10 million rupees (about $157,000).

In 2001, a 6-year-old boy named Michael Colombini died in Westchester, New York, after an oxygen canister flew at his skull during an MRI for a benign brain tumor. The boy's family and the hospital reached a $2.9 million settlement in 2009, according to news reports.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The most common MRI injuries, though, are burns, according to a 2008 report by The Joint Commission, a nonprofit healthcare accreditation agency. When metal is left inside a patient's body — or a tattoo containing metallic pigments is overlooked — the magnetic fields induced by the MRI can create electrical currents in that metal, potentially heating up the soft tissue around it.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.