In Photos: Hidden Maya Civilization

Hidden Civilization

Maya pyramids peek from the jungle in this aerial image from northern Guatemala. Scientists studying the ancient Maya culture have just completed a 810 square mile (2,100 square kilometer) survey of 10 sites in northern Guatemala using LiDAR, a technology that uses laser pulses to map topography, stripping away obscuring vegetation. [Read more about the Maya surveys]

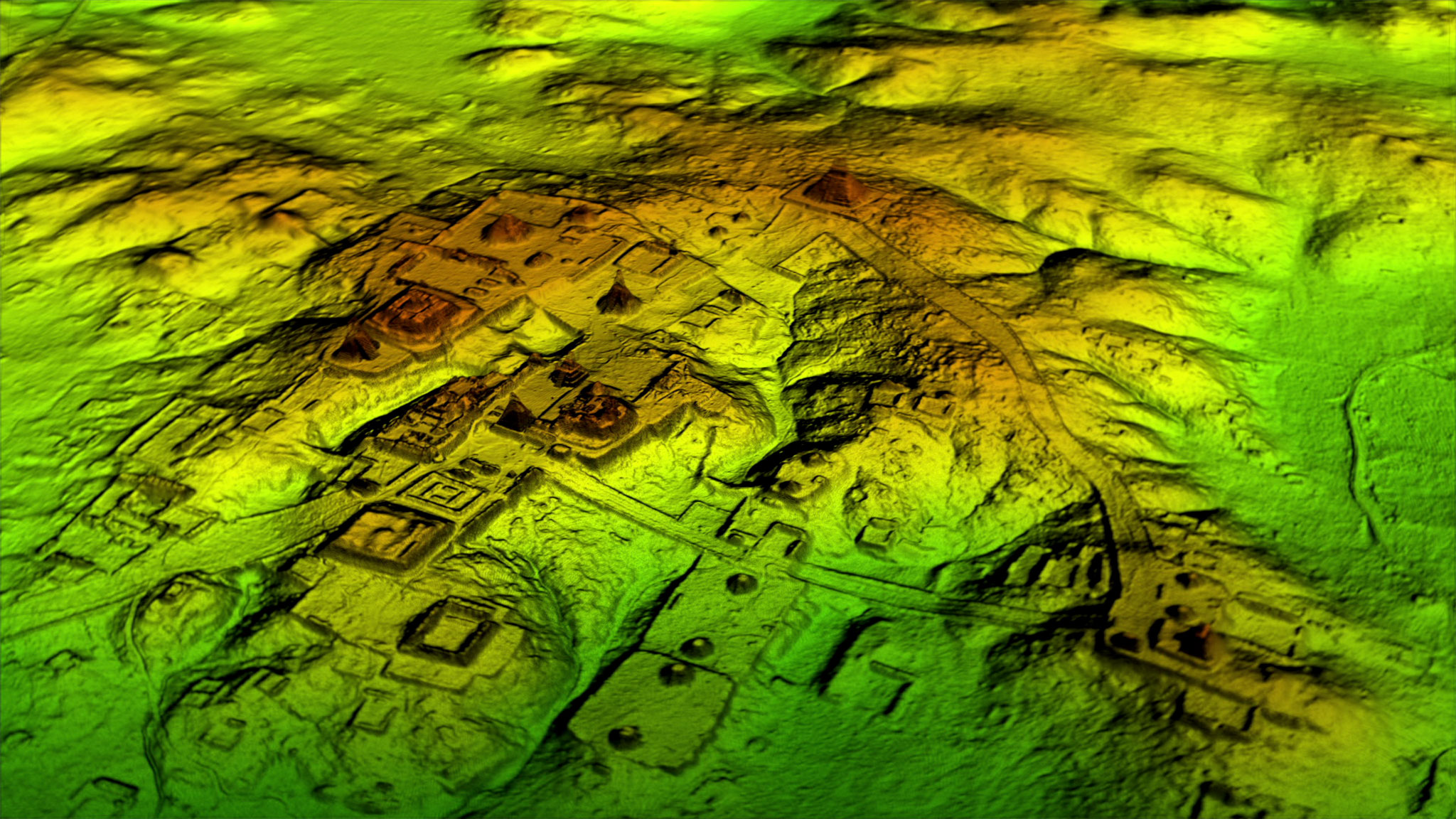

What Lies Beneath

The same site appears in much greater detail in a LiDAR image. Roads and foundations become apparent. In the new LiDAR survey, researchers discovered 60,000 structures that had never been mapped before, some in very well-researched Maya sites. Others were spread far and wide through the jungle.

Featureless Forest

The dense Guatemalan jungle hides evidence of ancient Maya settlements. Archaeologists say it's easy to walk within a few dozen feet of a structure and never even know it's there. Wide-ranging LiDAR surveys can map in a few hours what would have taken archaeologists decades.

"LiDAR is going to be to our understanding of settlement patterns of ancient societies what radiocarbon dating has been to our understanding of their chronologies, which is to say, revolutionary," said Maya archaeologist David Freidel of Washington University in St. Louis.

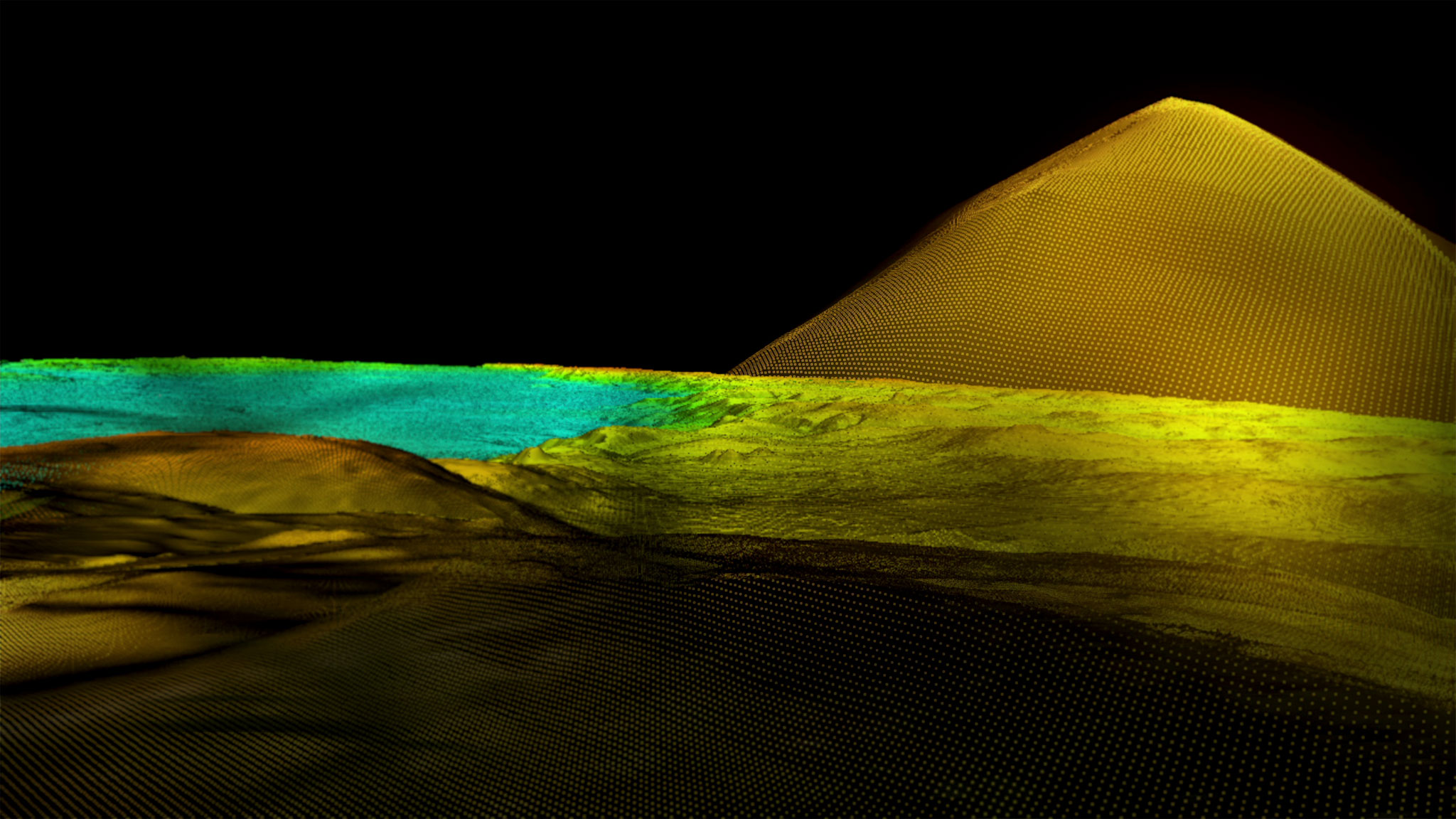

Hidden Worlds

That featureless forest in the previous image hides all sorts of ancient Maya secrets. This image shows a LiDAR scan of the same spot shown in the previous photograph. Architectural features hidden beneath dirt and plants suddenly become visible.

The new LiDAR survey provides a literal treasure map to lead researchers to new sites to excavate. Friedel and his team plan to spend the next three years investigating new features from the LiDAR survey in their study site, El Peru-Waka' in northwestern Peten.

Superimposed

The jungle photograph and the LiDAR scan are superimposed in this image, showing how Maya structures can be hidden in plain site in the dense vegetation. Archaeologists first used LiDAR to survey Maya areas in Belize in 2009. It's been "spectacularly successful," said University of Colorado, Boulder, anthropologist Payson Sheets. "As of right now," Sheets told Live Science, "only a teeny-tiny fraction of one percent of the Maya area has been covered in LiDAR, so the future is very bright."

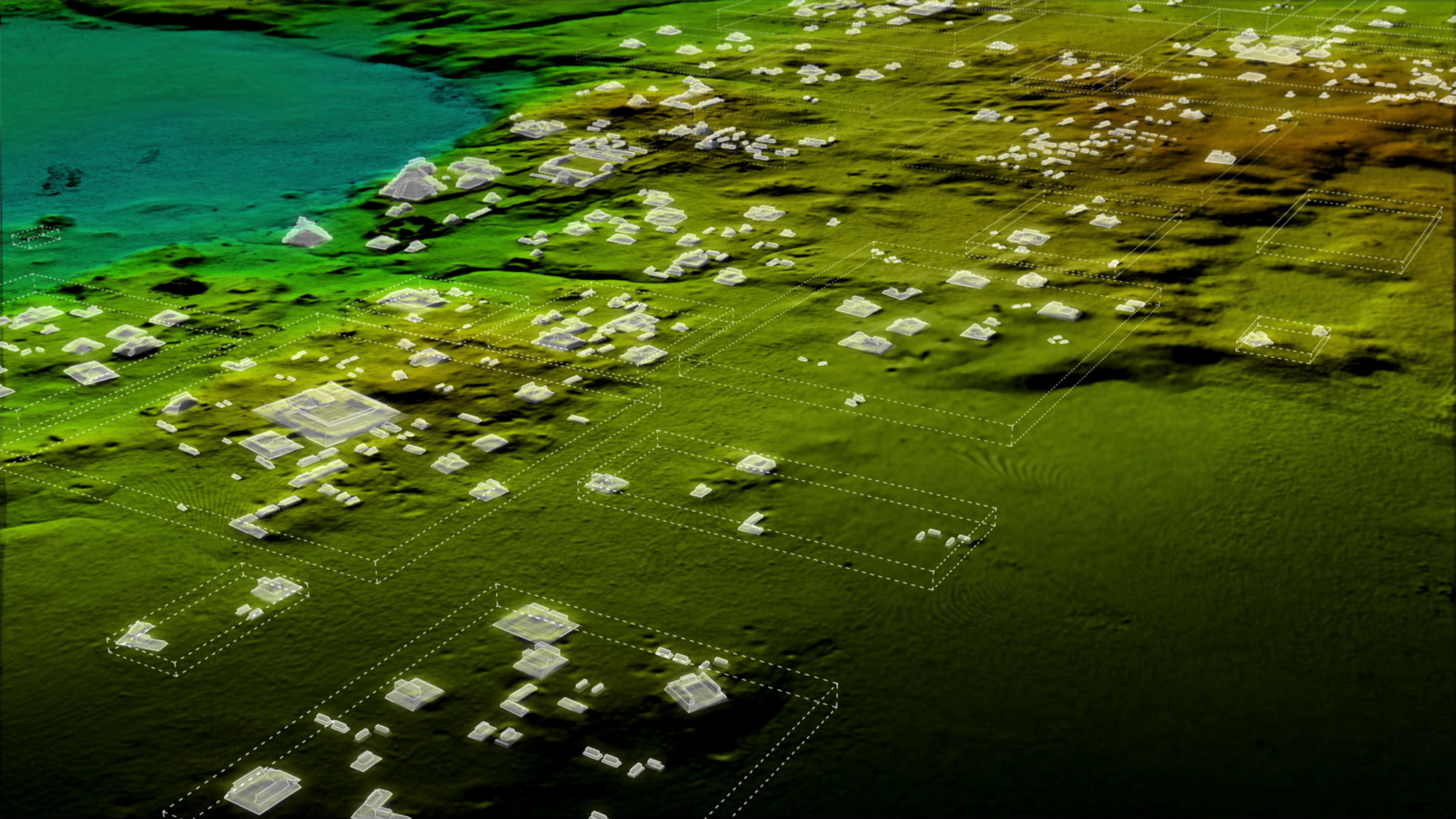

Living in the Landscape

Maya structures are scattered across the jungle in this LiDAR image taken over northern Guatemala. The findings of the survey suggest that the population was far denser in the Maya lowlands than previously believed, according to survey archaeologist Tom Garrison. That's a fascinating finding, said Maya expert Lisa Lucero of the University of Illinois, who was not involved in the project; today, slash-and-burn agriculture supports far fewer people, with far greater destruction. The ancient Maya were somehow managing the forests to support larger numbers of people, she said, and doing so in a more sustainable way.

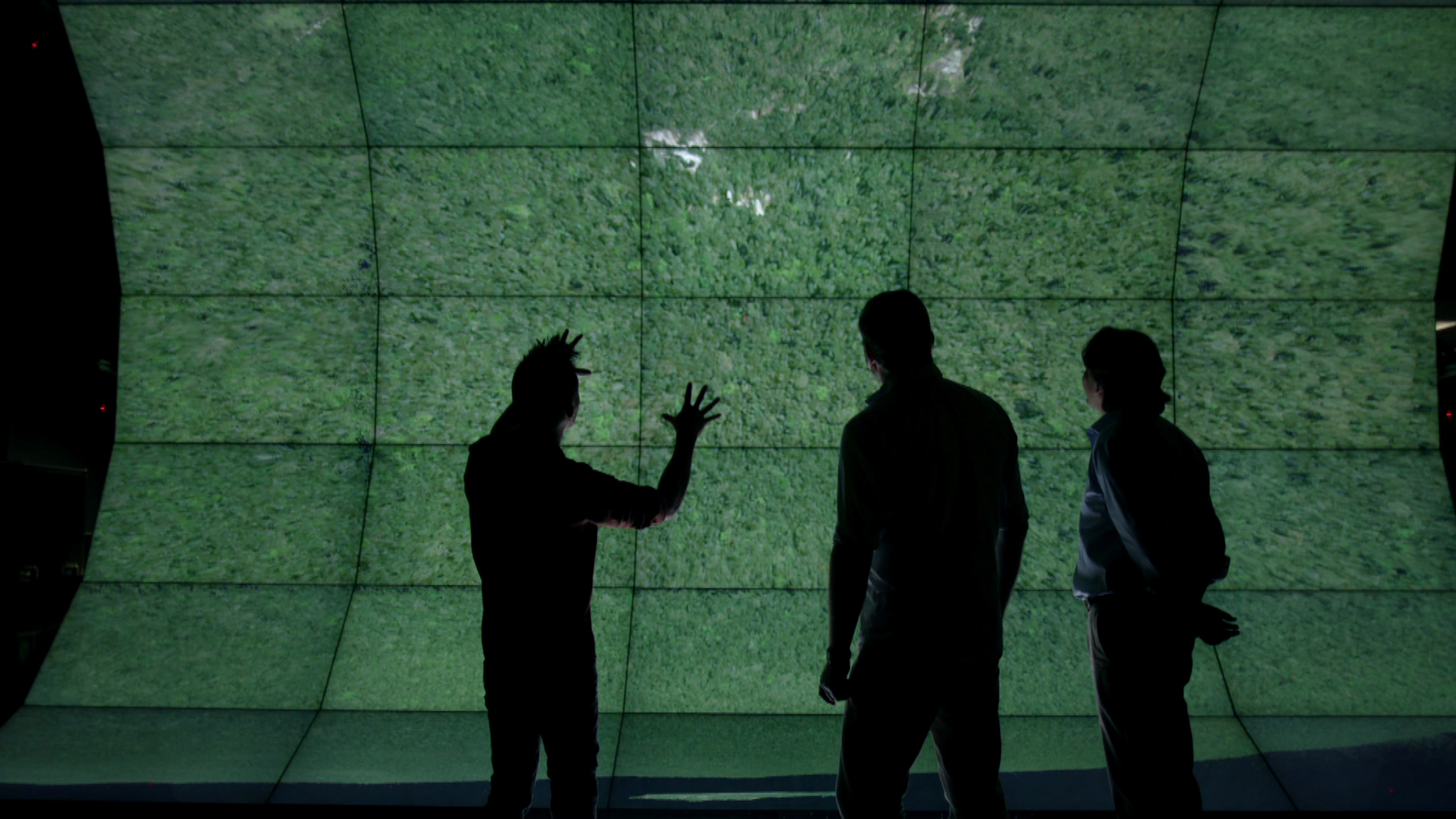

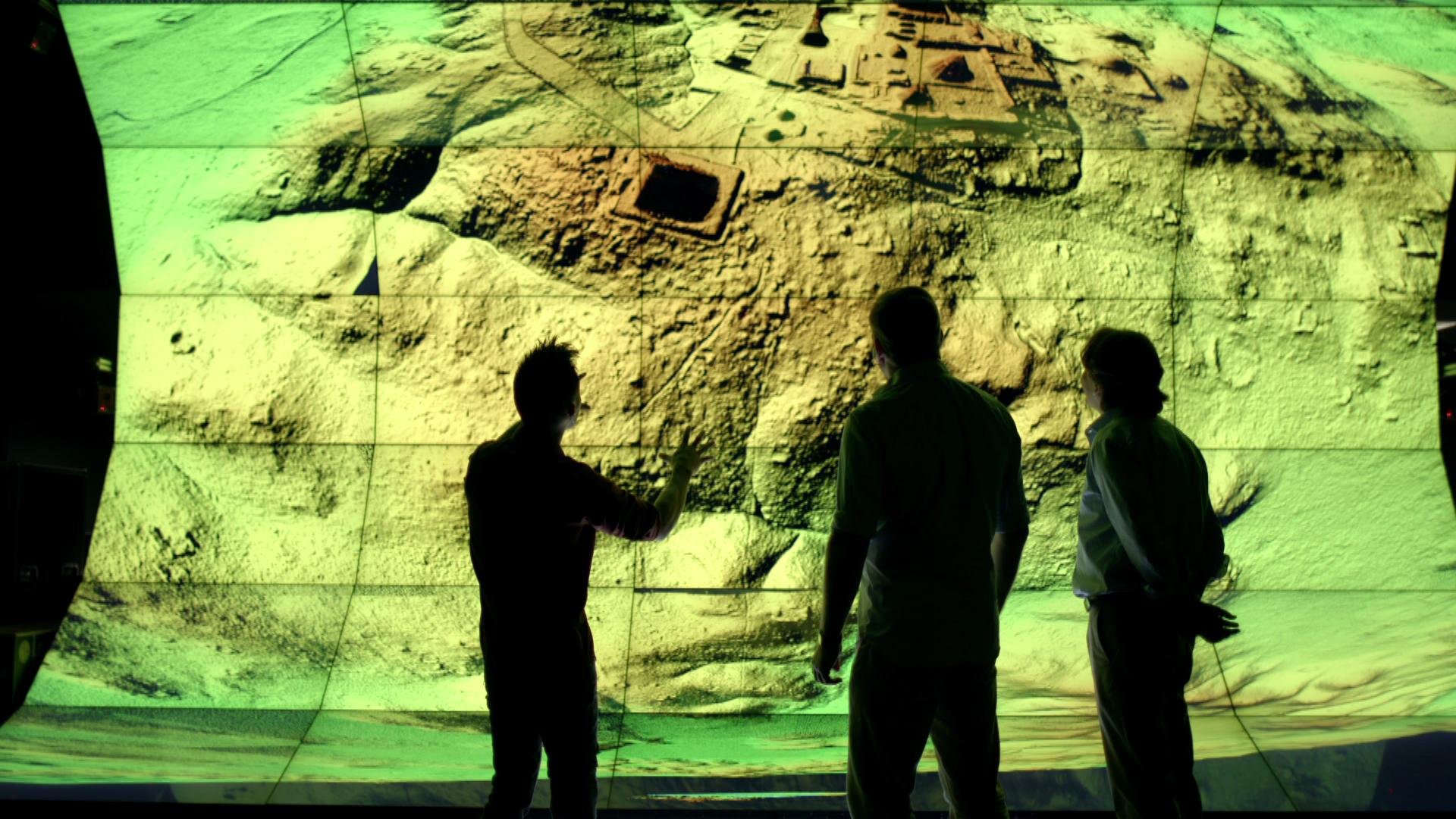

Guatemala from Above

Scientist Albert Lin (left), Tom Garrison (middle) and Francisco Estrada-Belli (right) examine the topography of northern Guatemala as seen by the naked eye. A new documentary, Lost Treasures of the Maya Snake Kings, will premier on Tuesday, Feb. 6 9/8c on the National Geographic channel to highlight some of the LiDAR discoveries.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A Lost World, Revealed

Albert Lin, Tom Garrison and Francisco Estrada-Belli look at the same scence through LiDAR, a view that reveals detailed topography and a whole host of structures swallowed by the Guatemalan jungle. Using LiDAR, Garrison and his colleagues discovered new fortifications near their study size of El Zotz in Guatemala. They hope to excavate the 30-foot (9 meter) wall in the coming field seasons.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.