Starfish Can See You … with Their Arm-Eyes

If you were to look at this little, funky starfish, there's a chance the well-armed sea creature would look back at you (though it may see a blurry version of you) — with its up to 50 eyes — all attached to the tips of its squishy limbs. And if you catch it at the right time, the little starfish might glow a vivid-blue hue.

This scenario comes courtesy of a new discovery. Scientists have found that starfish — previously thought to largely rely on smell when navigating the ocean floor — actually have the ability to see all around them, even in the deep sea where there isn't any sunlight, the researchers said.

But though they have eyes galore, starfish don't have 20/20 vision, said the study's senior researcher, Anders Garm, an associate professor of neurobiology at the Marine Biological Section of the University of Copenhagen, in Denmark. [Take our Vision Quiz: What Can Animals See?]

"Even the best starfish vision is still rather crude — about 500 times less acute than human vision," Garm told Live Science in an email. He added that starfish see only in black and white, not color.

Star vision

Researchers have known for about 200 years that most starfish species sport compound eyes at the tip of each arm. These eyes have multiple lenses, like an insect's peepers. Each small lens, known as an ommatidia, creates one pixel of the total image the animal sees. But scientists didn't test the visual acuity of these creatures until 2014, when Garm and a colleague revealed that the tropical starfish Linckia laevigata had eyes "capable of true image formation, although with low spatial resolution," and that the starfish used its vision to navigate the ocean floor, according to their study published that year in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

In 2016, Garm and his team showed that another starfish — the crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) — could also see images with its advanced compound eyes, according to a study published in the journal Frontiers in Zoology.

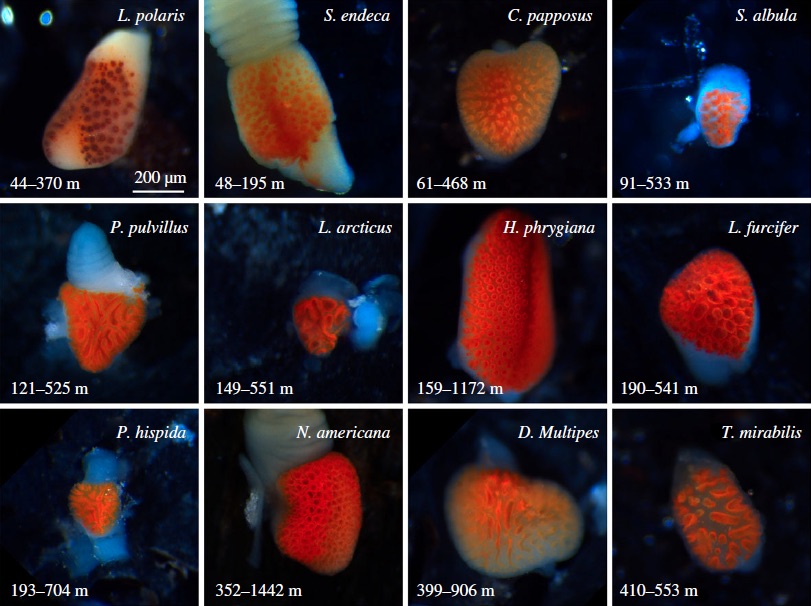

However, Garm had never tested the vision of deep-sea starfish, which live underwater in the inky blackness. So, in the new study, Garm and his colleagues studied 13 different starfish species living in shallow to deep waters off the coast of west, south and southeast Greenland, in the Arctic.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One of the starfish didn't have eyes, they found. This critter (Ctenodiscus crispatus) lives in the sediment, like other blind starfish, and probably uses its sense of smell to navigate, Garm said.

The other 12 starfish, even those that lived in a zone with no light — known as the aphotic zone — "still possessed eyes, and some of them with just as good or better spatial resolution as shallow-water species living in plenty of light," Garm said.

Two of the eyed species — Diplopteraster multipes and Novodinia americana — were also bioluminescent, meaning they could glow on their own. (This is different from biofluorescence, in which an organism absorbs light from an outside source, and glows by releasing that light at a lower wavelength.)

It's likely that the bioluminescent starfish use their vision to see glowing signals from other starfish, Garm said. "In other words, they probably flash light at each other to communicate things like reproductive state," he said.

It's also possible that D. multipes uses its vision to help it find tasty, deep-sea bacteria mats, which emit a faint light, the researchers said in the study.

The study will be published online Wednesday (Feb. 7) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.