Why Does the Tesla Look So Fake in Space? We Asked a Chemist

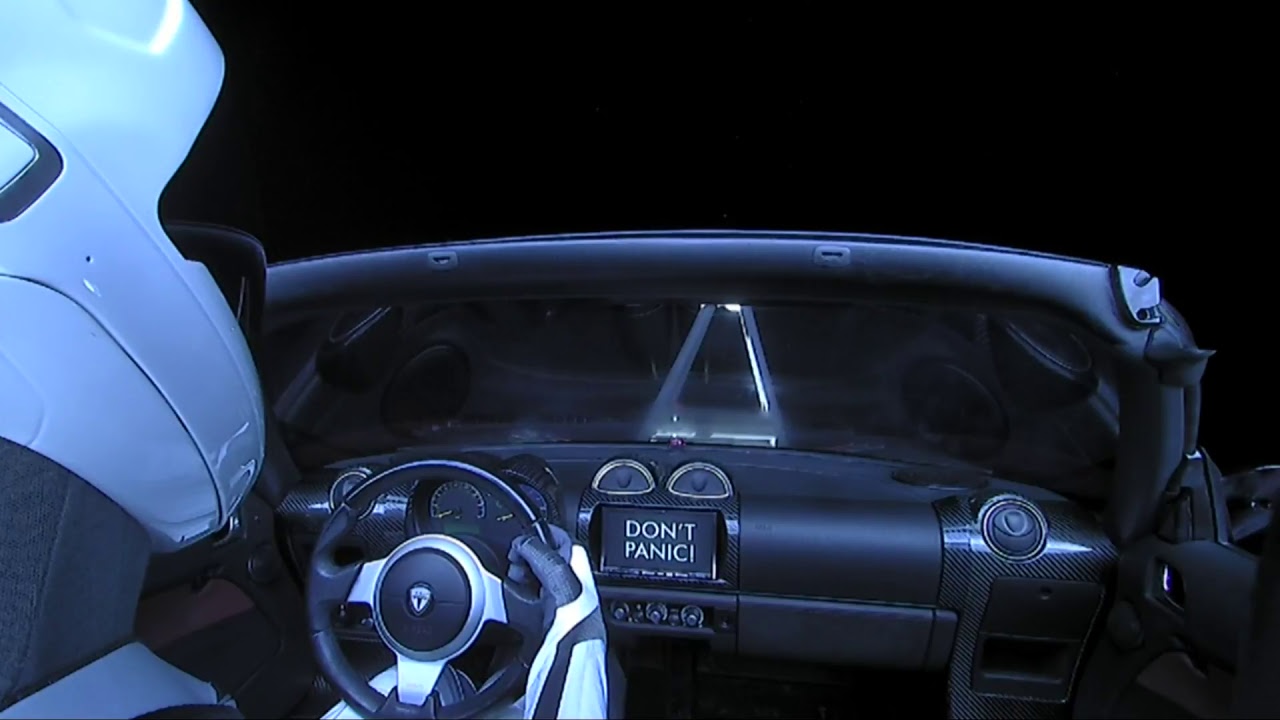

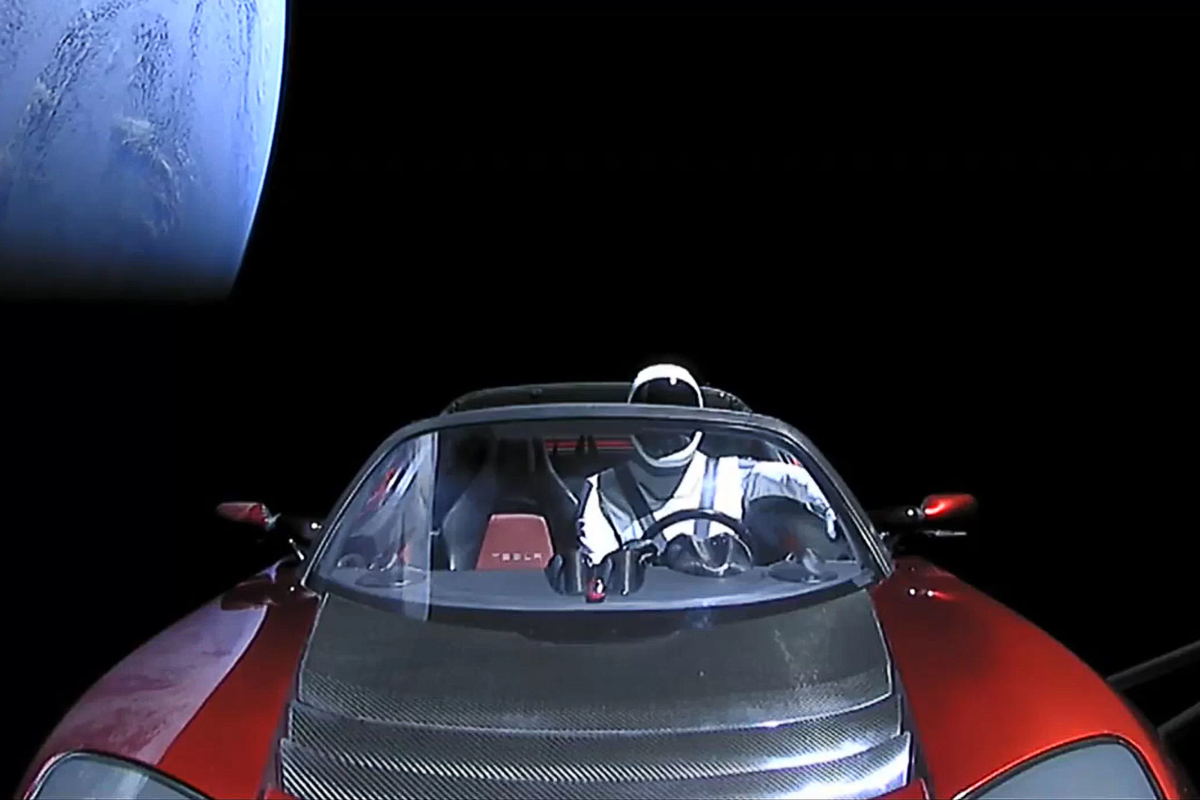

Even Elon Musk thinks his space-cruising midnight-cherry Tesla Roadster looks weird.

"It looks so ridiculous and impossible," the SpaceX CEO told reporters after the Falcon Heavy megarocket launched the car into space yesterday (Feb. 6). "You can tell it's real because it looks so fake, honestly."

Musk went on to say that colors, in general, look strange in space, because "there's no atmospheric occlusion. Everything's too crisp," he said. But what did he mean by this, and is it true that colors in space don't look the same as they do on Earth? [The 18 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics]

First off, yes — colors do look "fuzzier" on Earth than they do in space, said Rick Sachleben, a retired chemist in Boston who is a member of the American Chemical Society's panel of experts.

Think of it this way: Light can travel through different mediums — including air, water and the vacuum of space — each of which has a different refractive index, he said. That is, these mediums bend light differently, which explains why colored light doesn't look the same in one medium as it does in another.

Furthermore, when light travels through the Earth's atmosphere, it passes through air that contains particles, such as dust, soot, smoke and liquid droplets. The air also has varying densities depending on how much water it contains and its temperature, Sachleben said. For instance, the air at the top of Mount Everest is less dense than at sea level, which is why breathing at Everest's peak is challenging.

These factors — air's particles and properties — can change the way colors look on Earth, Sachleben told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The light scatters off of those particles," he said. "When it hits a piece of dust, it bounces off of it. And then it hits another one, and it scatters off of that one." That's why "the image we see [on Earth] is fuzzier, less distinct," he said. "In space, you don't have that."

In space, there's barely anything to bend or block light. That's why pictures taken by the Hubble Space Telescope are so much sharper than images taken from Earth-based telescopes, Sachleben said.

"You get these incredibly good pictures when you're in space," he said. Other images snapped in space, such as the famous "Blue Marble" pictures, also show clear and crisp colors. But perhaps people didn't realize it, because these images weren't as crazy-looking as a Tesla Roadster heading toward the asteroid belt, Sachleben noted.

Because colors in space look so sharp, pictures and videos taken there may look as if someone visually edited them. This is likely why Musk joked that the Roadster images looked "fake," Sachleben said.

However, Sachleben noted that he's never heard of "atmospheric occlusion," the term Musk used. It's likely that Musk was referring to particles in Earth's air that block and scatter light, but it's hard to say for sure, Sachleben said.

"It's probably [Musk] speaking off the cuff and using terminology that's not necessarily incorrect, but not standard," Sachleben said.

SpaceX didn't immediately respond to a request for comment, but Live Science will update the story if the company responds.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.