Deep-Sea Volcanic Vents Incubate Eggs for These Underwater Moms

Skates — flat, diamond-shaped fish that are related to sharks and rays — incubate their eggs for as much as four years or more, longer than most animals on Earth. But scientists recently discovered that skates may speed up the lengthy process by turning up the warmth on their egg cases.

And they do this in the most badass manner possible — by harnessing the heat of deep-sea volcanoes.

The Pacific white skate (Bathyraja spinosissima) deposits many of its developing egg cases — each about the size of a cellphone — close to hydrothermal vents, where they soak up the extra heat. While nesting behavior that uses an active volcanic source to incubate eggs is known from a few species on land, it has never been seen in a marine environment before, the researchers reported in a new study. [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

"This is the first record of a hydrothermal vent habitat serving as an egg-case nursery site, a discrete habitat with extremely high densities of egg cases when compared to surrounding similar habitats," the study's lead author, Pelayo Salinas-de-León, a senior marine ecologist with the Charles Darwin Foundation in Galápagos, Ecuador, told Live Science in an email.

White skates are cartilaginous fishes, lacking hard, bony material in their skeletons. They are among the deepest-dwelling skates in the ocean, living more than 9,843 feet (3,000 meters) below the surface and preferring rocky parts of the seafloor, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN).

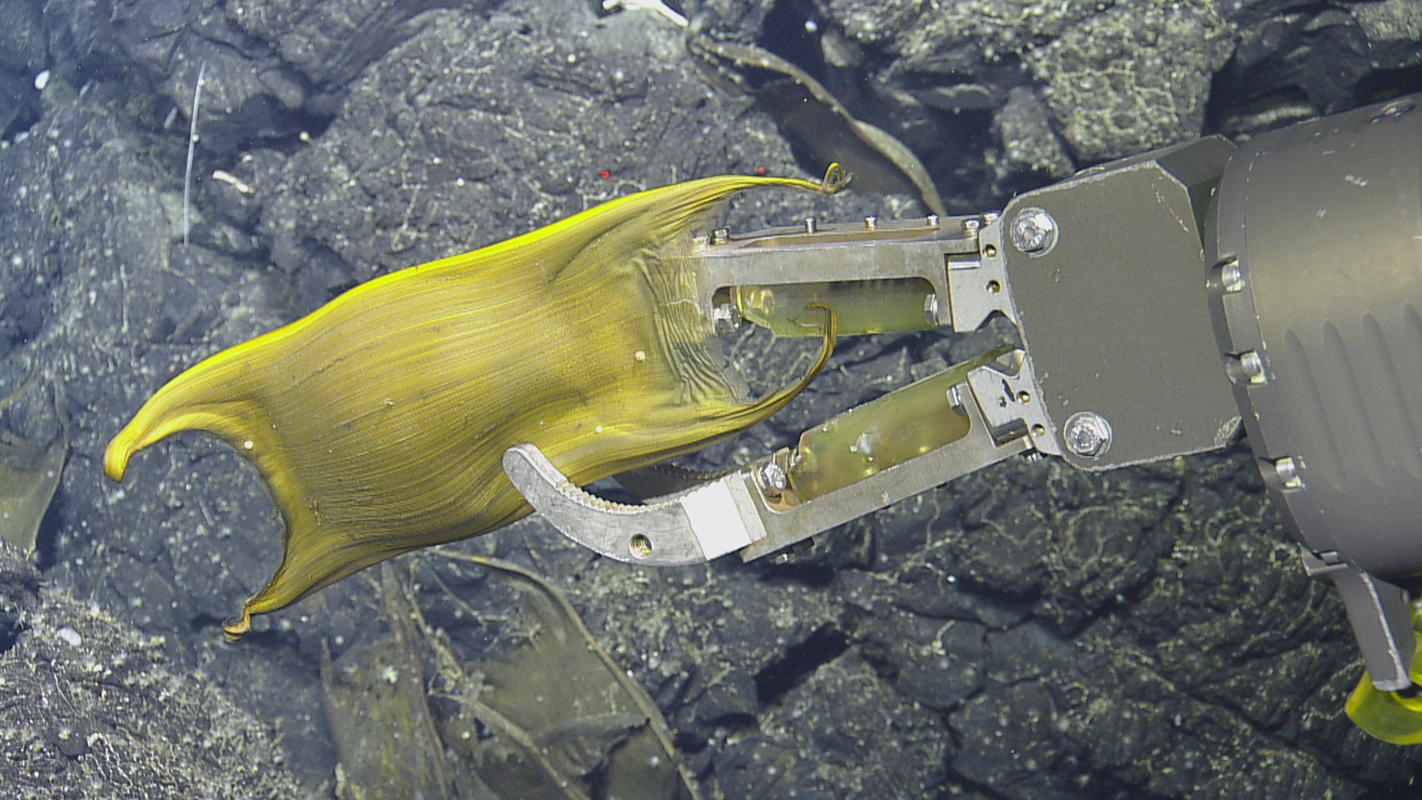

The skates reproduce by laying groups of eggs encased in rectangular pods that resemble large and leathery ravioli, each corner tipped with four slender, tapering "horns." Made of collagen secreted from an oviduct, the water-permeable pods — which sometimes wash up on beaches after the eggs have hatched — are whimsically known as "mermaid purses," according to a study published in 1980 in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Inside the pods, the eggs incubate for years at a stretch — at least 1,500 days in waters where the average temperature is 36.9 degrees Fahrenheit (2.7 degrees Celsius), the study authors reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

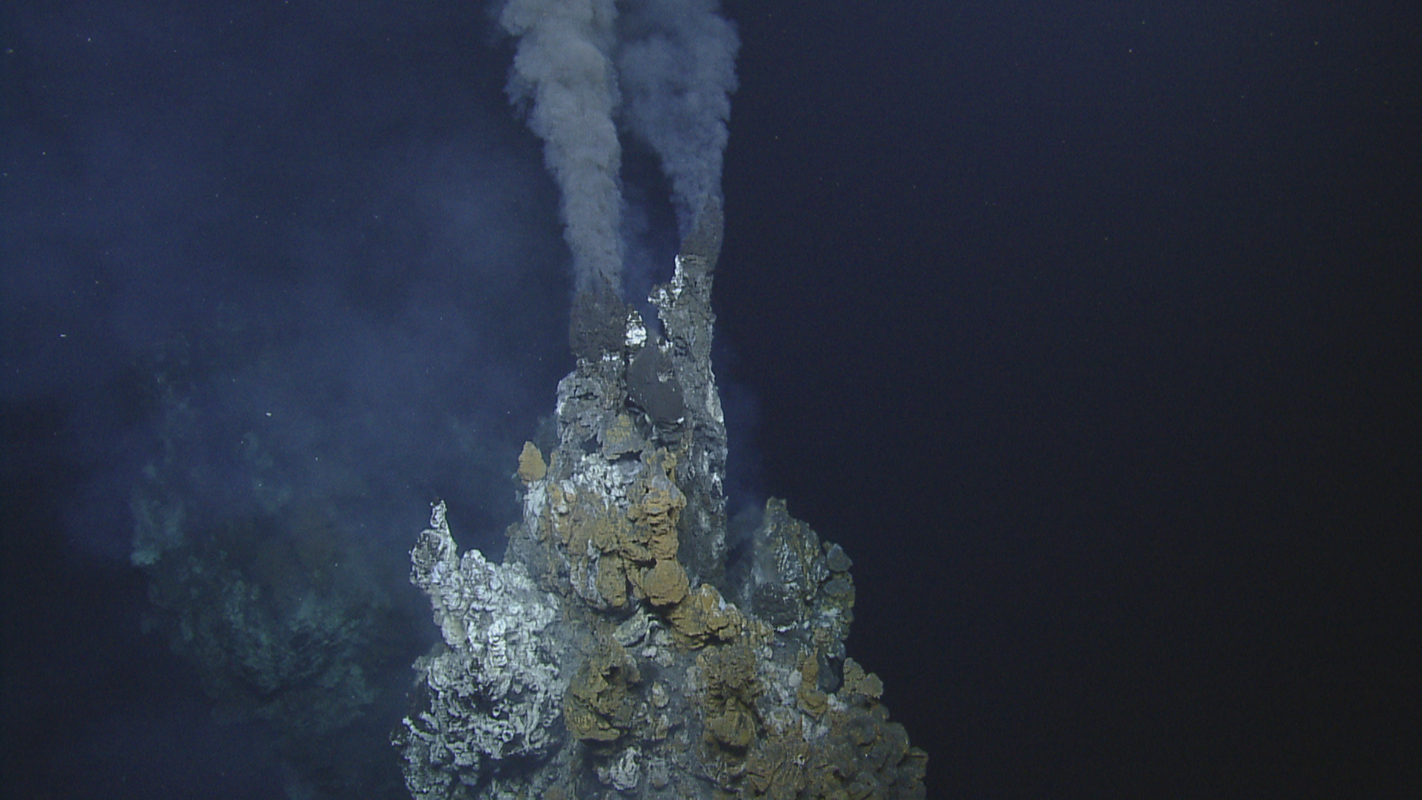

To learn more about how skates interact with their deep-sea environment, the scientists investigated a hydrothermal vent field — a collection of fissures in the sea floor near a volcanically active area — in the eastern tropical Pacific near the Galapágos, north of the Darwin Islands. At the outset of the expedition in 2015, "we hardly knew anything about Galapagos deep-sea ecosystems," Salinas-de-León said.

Using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) named "Hercules," the researchers observed caches of skate egg pods, though they didn't see any skates. In total, they counted 157 egg cases in the area, the majority of which (58 percent) were positioned no more than 66 feet (20 meters) from the hottest vents, known as "black smoker chimneys," Salinas-de-León said.

Elevated water temperatures in these volcanic zones — measured at around 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4.5 degrees Celsius) in one location — could warm the skates' eggs enough to speed their incubation, according to the study.

Evidence from the fossil record suggests that some sauropod dinosaurs during the Cretaceous period incubated their eggs in volcanically warmed soil. And the bird known as the Polynesian megapode (Megapodius pritchardii) nests by burrowing into earth warmed by volcanoes on its island home of Tonga.

However, before this study there was no evidence that any marine creature incubated its eggs with volcanic heat, the study authors reported.

"It highlights how little we have explored and therefore understand about the deep sea," Salinas-de-León wrote in an email.

Skates, as well as sharks and rays, belong to the fish group known as Chondrichthyans, which has been especially hard-hit by overfishing in recent decades — about 25 percent of the species in this group are facing extinction, the scientists wrote in the study. Those that live in deep water are more at risk, as they tend to grow slower and mature later, making it difficult for populations to rebound when their numbers are depleted.

Understanding the reproduction and habitat requirements of these vulnerable deep-sea skates is therefore critical for strategizing their ongoing protection and conservation, particularly in a warming world, the researchers wrote.

"Further research should focus on identifying and promoting the protection of additional Chondrichthyan deep-sea nurseries, given the continuous expansion of fisheries towards the deep sea and the intrinsic vulnerability of this group of species," the study authors concluded.

The findings were published online today (Feb. 8) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.