Bizarre 'Spider Stones' Found at Site of Neolithic Sun-Worshipers

Strangely marked stones and other artifacts unearthed on the island of Bornholm in Denmark have raised new mysteries about a Neolithic sun-worshipping religion centered there about 5,000 years ago.

The new finds include "spider stones," inscribed with pattern like a spider's web, and a piece of copper from a time when the metal could not be made by the island's Stone Age inhabitants, say the researchers.

The handful of newfound spider stones look a little like hundreds of inscribed "sun stones" or "solar stones" — solsten in Danish — found since the 1990s amid the remains of an earthen-walled Neolithic enclosure, about 650 feet (200 m) across, at the Vasagard archaeological site on Bornholm in the Baltic Sea, between the southern tip of Sweden and the coast of Poland. [See Images of the Strange Stones Found in Denmark]

The round, hand-sized sun stones are made from a type of local stone that was polished and then deliberately marked, using a second piece of stone, with patterns of radiating lines thought to symbolize the sun.

Similar radiating patterns have been inscribed or painted on rock at several prehistoric sites around the world.

But the spider stones found last year are inscribed with distinct straight lines running between and across an underlying pattern of radiating lines, giving them the appearance of a spider's web, according to the researchers.

Spider stones

Archaeologists have found only about half a dozen of the so-called spider stones among the several hundred sun stones at the Vasagard site, which archaeologists think was a ceremonial center for Neolithic sun-worshippers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In his research, Finn Ole Nielsen, the director of Bornholm Museum, could find just a single symbolic use of spider webs in Europe, painted on the ceiling of a Medieval church in France, where it's thought to symbolize heaven or the transition between life and death.

But archaeologists would never know for certain what the original meaning was for the people who inscribed the patterns 5,000 years ago, Nielsen said.

In 2016, scientists found fragments of about 10 roughly rectangular "map stones" or "field stones" during excavations at the western end of the Vasagard site; these may be the earliest known examples of symbolic maps of land, they said.

Archaeologist Fleming Kaul of the National Museum of Denmark told Live Science that the map stones might have been used in a religious ceremony to bless the farmland of a family or community with good weather for crops.

Mysterious structures

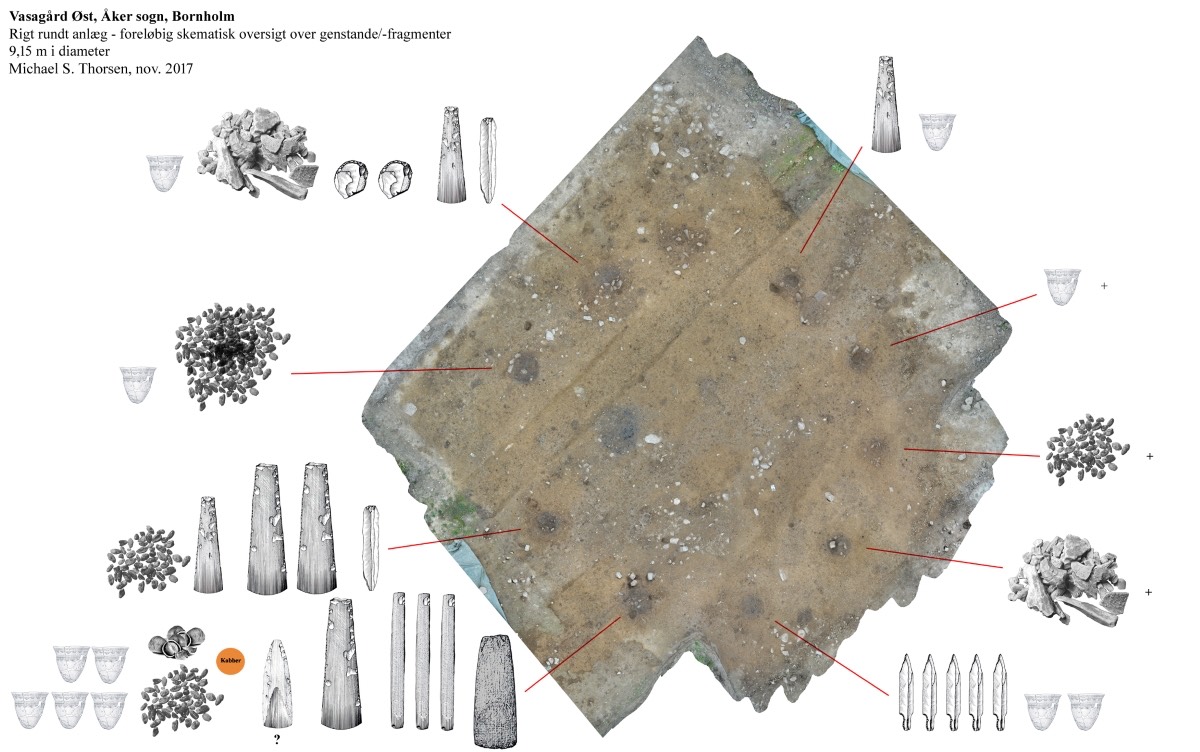

Archaeologists have also excavated the remains of several round timber structures, some more than 30 feet (9 m) across, that have been found at different places around the main earthen-walled enclosure at Vasagard. [7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot]

In the remains of the largest timber structure, excavated last year, they found a 1.6-inch-long (4 centimeters) piece of copper, dating from a time when the local Stone Age people were not thought to have access to that metal.

The fragment was probably part of an imported copper axe buried as a sacrifice, archaeologist Michael Thorsen of Bornholm Museum told Live Science.

Because copper couldn't be made locally at that time, the original copper object must have travelled or been traded as a prestige item over a long distance, from the Mediterranean or the Balkans, before it was finally offered as a ritual sacrifice on Bornholm, he said.

Thorsen said the elaborate construction of the largest timber structure, which was built around 10 wooden posts measuring more than 1.5 feet (0.5 m) in diameter, showed it was not a normal habitation.

"I think the most obvious function is some kind of religious building," he said, adding that it was possibly a spirit house used in shamanic rituals, or as an enclosure for housing the bodies of the dead during funeral ceremonies.

After being used for its unknown purpose, the timber structure was ceremonially demolished, and the post holes filled with sacrificial objects, including burned grain and burned stone axes, he said: it was in one of these post holes that the copper fragment was found.

"This copper must have come a very long way," Thorsen said. "For me, it just makes the structure even more important, because they were offering a rare piece of copper like this."

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.