The Color of Blood: Here Are Nature's Reddest Reds (Photos)

Reds in nature

It's customary to give ravishing red gifts on Valentine's Day — think red roses, red boxes of chocolate or red candy hearts. Or even your own heart (figuratively speaking).

But many decry the holiday for its artificial and forced romance. So, how do we get back to something genuine?

We'll start by going back to nature and revealing its reddest reds. There's nothing fake about these colors, which surround us all year — not just on Valentine's Day.

Red feathers

The male northern cardinal (Cardinalis cardinalis) sports bright-red plumage. And it's all thanks to its diet, according to a 2016 study in the journal Current Biology that found the genes responsible for red bird feathers.

Red-feathered birds get their unique coloring from a diet of certain seeds, leaves and fruit that contain organic yellow pigments, known as carotenoids. Once they eat these yellow pigments, an enzyme in the birds catalyzes a reaction that converts them into red ketocarotenoids — that is, red pigments.

Red and yellow birds have this enzyme in their eyes, which helps them see color. But in red birds, this enzyme is also active in their skin, feathers and liver, the researchers found.

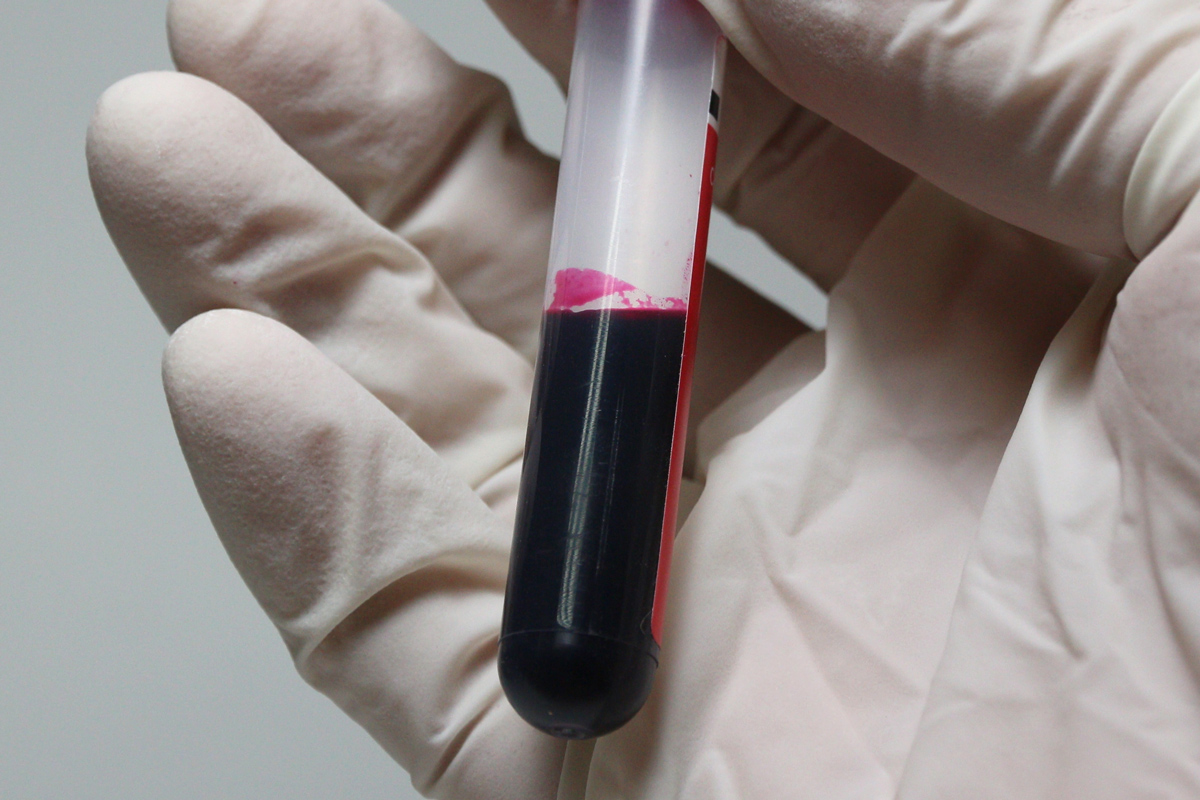

Blood

The protein hemoglobin gives blood its red color. This protein is made of subunits called hemes, which can bind iron molecules that, in turn, can bind oxygen, according to the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB).

Blood becomes red when the iron and oxygen bind. "Even more specifically, it looks red because of how the chemical bonds between the iron and the oxygen reflect light," UCSB wrote.

Take a deep breath this Valentine's Day — that breath will oxygenate your blood, which will then carry that oxygen to all of your organs.

Cinnabar

Cinnabar — also known as vermilion, or mercury sulfide (HgS) — is a naturally red ore that contains mercury. (An ore is a naturally occurring solid that contains an extractable metal or mineral.)

Paleolithic painters used cinnabar to decorate caves in Spain and France about 30,000 years ago, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry.

Cochineal insect

The cochineal (Dactylopius coccus) — an insect found in the southwestern United States and South America — is used as a red dye in all kinds of foods.

"Anytime you see an ingredients list that includes carmine, cochineal extract or natural red 4, you can be sure that there's a little powdered bug therein," Live Science previously reported.

In fact, Starbucks previously used the cochineal to redden its Strawberries & Crème Frappuccino, Strawberry Banana Smoothie and some of its desserts. But the company stopped using the insect after an outcry from vegetarians and vegans in 2012, according to CNN Money.

Flowers

It's not just roses that are red. Poppies, petunias and zinnias are, too. These flowers get their red hue from pigments known as anthocyanins.

Red, purple or blue plants have higher concentrations of anthocyanins than of chlorophyll, Live Science previously reported.

Chlorophyll can absorb red and blue light, but not green light, so it appears green. In contrast, anthocyanin can absorb green, but not red, blue or purple light. So it looks like these colors to the human eye.

Foods

Red is certainly a popular color for foods. To name a few, there are beets, strawberries, radishes, kidney beans, apples, watermelon, red onions, pomegranates and tomatoes.

Now that the cochineal insect is falling out of favor as a food dye, some of these foods are picking up the slack. For instance, Starbucks said it planned to use lycopene, a tomato-based dye, to color its drinks, according to NPR.

Red maples

It's common knowledge that leaves turn yellow and orange in the fall and winter. These colors are actually in the leaves the entire year, but are only visible once trees stop making chlorophyll when the weather gets cold.

Red leaves, however, are another story. The red comes from anthocyanin, the same pigment that makes flowers red. Trees begin to produce anthocyanins in the fall, when it acts as an antifreeze to protect the leaves from the cold. But like its yellow and orange brethren, these red leaves eventually fall to the ground.

It's truly a mystery why some trees, such as red maples, spend so much energy making anthocyanins in leaves that will soon die, Live Science previously reported.

Red tides

Red tides are the bane of any beachgoer, because it means swimmers can't safely go into the water.

These tides occur when certain types of algae have a population boom. Millions of algae can change the color of the water, often to a rusty red.

Algae blooms can deplete nitrates and phosphates in the water, leading to an imbalance in marine- nutrient cycles and the animals dependent on them, Live Science previously reported. The blooms can also release toxins into the water, affecting marine life and swimmers.

Red heads

Three common variants in the gene MC1R give redheads their distinctive red hair, Live Science previously reported. But red hair is recessive, so a child must get these variants from both parents in order to sport red locks.

Some Neanderthals — the closest extinct relative of modern humans — also had red hair. But the gene variant that gave them the red hue is different than the one found in people today, Live Science previously reported.

Red rocks

The mountains in China's Zhangye National Geopark (shown here) are dramatically red. So are the red rocks of the Grand Canyon and Arizona's Vermilion Cliffs.

These rocks are red because of iron, which bonds with other elements, such as oxygen, to form minerals known for their red, rusty hue, Live Science previously reported.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.