Hidden Artwork Found Beneath Picasso 'Blue Period' Masterpiece

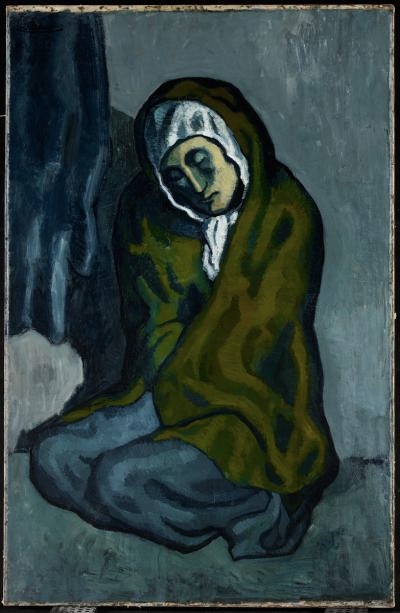

Pablo Picasso painted one of his "Blue Period" masterpieces, one showing a crouching, cloaked woman, on top of another artist's work.

A new examination of the painting, "La Miséreuse Accroupie," or "The Crouching Beggar," reveals that Picasso painted over a landscape made by another artist, flipping the canvas 90 degrees and using what was once a cliff top as the line of the cloaked woman's back.

The discovery was part of a larger project looking at Picasso's works, including his sculptures. In separate findings, the same research team was able to trace the metals in several of Picasso's bronzes to specific foundries, and to track how wartime metal shortages in the 1940s affected the artist's materials. [11 Hidden Secrets in Famous Works of Art]

Painting and repainting

Picasso, born in 1881, was one of the pioneers of Cubism, a style of art that depicts objects abstractly and from multiple points of view at once. "La Miséreuse Accroupie" is a more realistic composition, showing a woman in a green cloak and blue dress crouching against a gray-blue background. Picasso painted her during his "Blue Period" of 1901 to 1904, when he rarely used shades other than blue and blue-green.

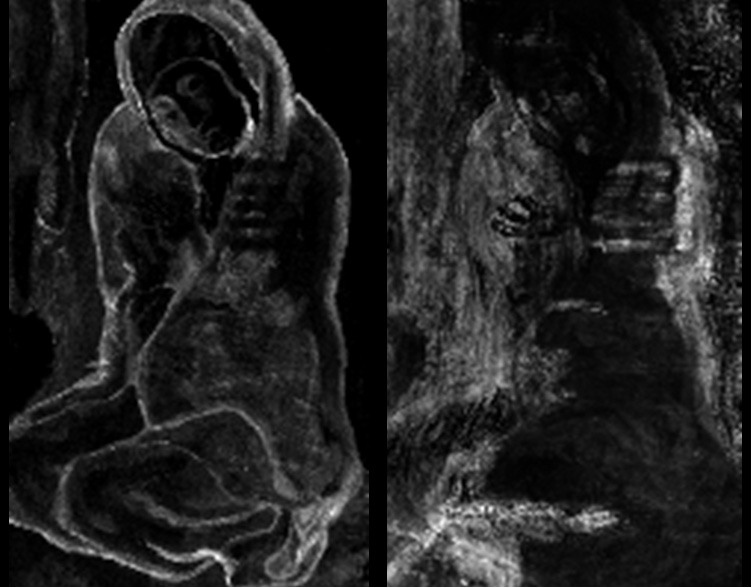

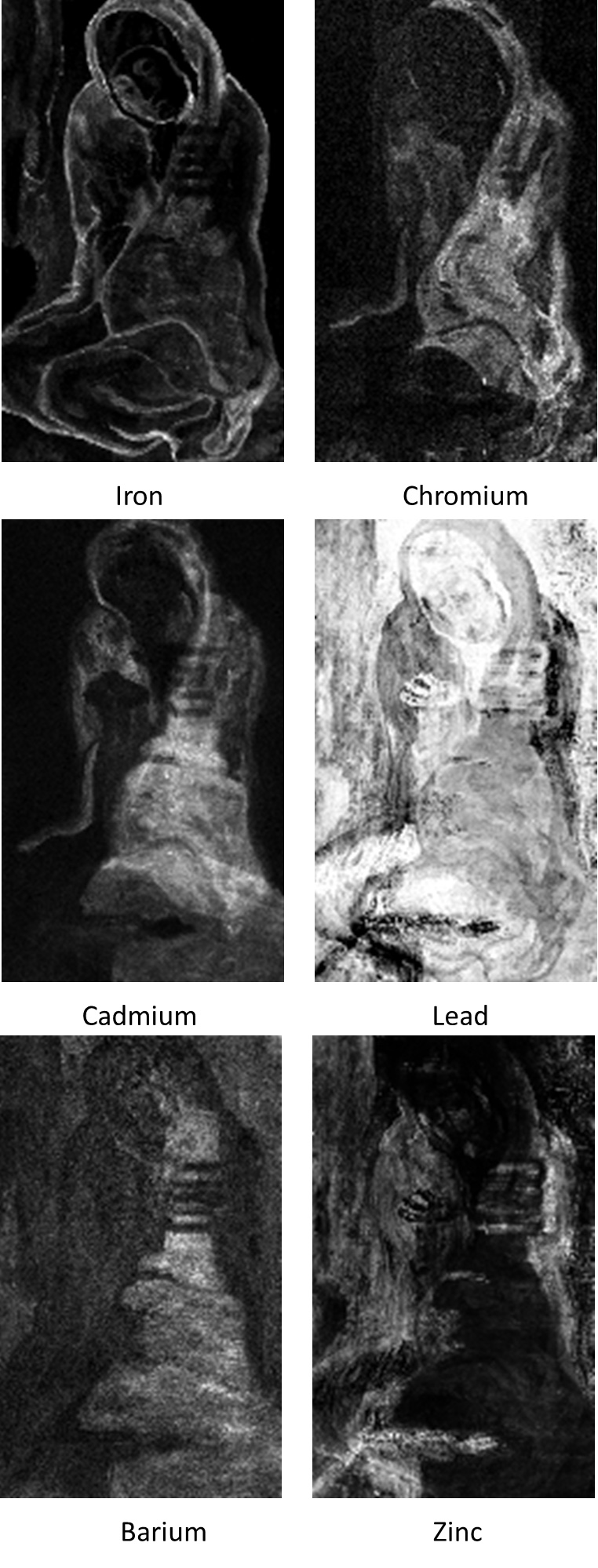

Researchers from Northwestern University and the Art Institute of Chicago's Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., used non-invasive imaging methods to peek beneath the visible layer of oil paint on the artwork. Specifically, the researchers used X-ray fluorescence, which can reveal the elements that make up a material, along with a method called infrared reflectance hyperspectral imaging, which can pick up images in both visible and near-infrared light.

Collectively, the methods revealed not only that Picasso recycled his canvas from an unknown artist, but also that he initially painted the woman with her right arm and hand exposed, holding a disk. Ultimately, Picasso changed his mind and painted over the limb with the green cloak. Different elements in the yellowish paint of the arm and disk revealed their presence when compared to the elements in the blue-green paint overlying them, the researchers said. [In Photos: Van Gogh Masterpiece Reveals True Colors]

"We now are able to develop a chronology within the painting structure to tell a story about the artist's developing style and possible influences," Sandra Webster-Cook, the senior conservator of paintings at the Art Gallery of Ontario, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sculpting history

The investigation of Picasso's sculptures, on the other hand, focused more on materials than artistic process. The same Northwestern University and Art Institute of Chicago-led team used X-ray fluorescence to determine the composition of metals that made up the alloys used in 39 Picasso bronzes cast between 1905 and 1959 and 11 sheet-metal sculptures made in the 1960s, no more than a decade before Picasso's death in 1973.

Five of the bronzes cast in Paris during World War II were made in the foundry of French metalworker Emile Robecchi, the researchers found. Robecchi was known to have collaborated with Picasso. Intriguingly, the alloys used in the casts during this period changed dramatically from sculpture to sculpture, probably because metal was scarce due to German appropriation of materials from France to fuel the German war effort, the researchers said.

Picasso also used silver to sculpt details on his cast-iron sculpture "Head of a Woman" (1962), the researchers discovered.

"In the context of increased material studies of Picasso's painting practices, our study extends the potential of scientific investigations to the artist's three-dimensional productions," materials scientist Emeline Pouyet of the Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts said in a statement. "Material evidence from the sculptures themselves can be unlocked by scientific analysis for a deeper understanding of Picasso's bronze sculpture-making process and the history of artists, dealers and foundrymen in the production of modern sculpture."

The findings will be presented today (Feb. 17) at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Austin, Texas.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.