Secret to Great Pyramid's Near-Perfect Alignment Possibly Found

Though it's slightly lopsided, the towering Great Pyramid of Giza is an ancient feat of engineering, and now an archaeologist has figured out how the Egyptians may have aligned the monument almost perfectly along the cardinal points, north-south-east-west — they may have used the fall equinox.

The fall equinox occurs halfway between the summer and winter solstices, when Earth's tilt is such that the length of the day and night are almost the same.

About 4,500 years ago, Egyptian pharaoh Khufu had the Great Pyramid of Giza constructed; it is the largest of the three pyramids — now standing about 455 feet (138 meters) tall — on the Giza Plateau and was considered a "wonder of the world" by ancient writers. [In Photos: Looking Inside the Great Pyramid of Giza]

Turns out, the pyramid builders somehow designed this ancient wonder with extreme precision.

"The builders of the Great Pyramid of Khufu aligned the great monument to the cardinal points with an accuracy of better than four minutes of arc, or one-fifteenth of one degree," Glen Dash, an engineer who studies the Giza pyramids, wrote in a paper published recently in The Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture.

The pyramid of Khafre (also located at Giza) and the Red Pyramid (located at the site of Dahshur) are also aligned with a high degree of accuracy, Dash noted. "All three pyramids exhibit the same manner of error; they are rotated slightly counterclockwise from the cardinal points," Dash wrote.

For over a century, researchers have proposed different methods used by the ancient Egyptians to align the pyramids along these cardinal points with such accuracy. In his paper, Dash demonstrates how a method that makes use of the fall equinox could have been used.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shadows in Connecticut and Giza

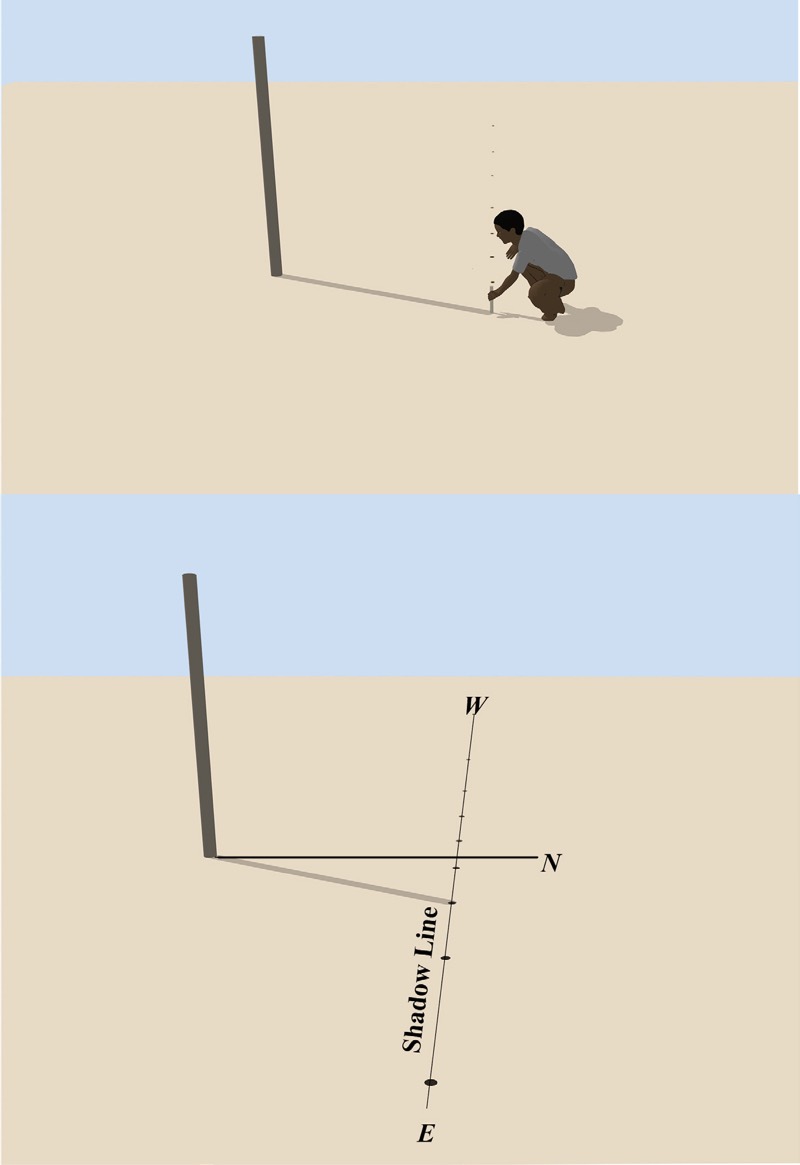

In his experiment — which he conducted in Pomfret, Connecticut, on Sept. 22, 2016 (the day of the fall equinox) — Dash placed a rod (sometimes called a "gnomon" by modern-day surveyors) on a wooden platform and marked the location of the rod's shadow throughout the day.

"On the equinox, the surveyor will find that the tip of the shadow runs in a straight line and nearly perfectly east-west," Dash wrote. The degree of error is slightly counterclockwise, similar to the error found in the Great Pyramid, Khafre Pyramid and Red Pyramid, Dash found. The tilt of Earth on the fall equinox allows the shadow to run in this east-west direction, Dash wrote.

Though the experiment was conducted in Connecticut, the technique should also work at Giza, Dash said. For the technique to work, the ancient Egyptians (or any surveyor) would ideally need a "clear sunny day, like most of the days at Giza. An occasional cloud would not be a problem," Dash told Live Science. The rod could have been placed on a wooden platform or the ground at Giza, Dash said. The Egyptians could have determined the day of the fall equinox by counting forward 91 days after the summer solstice, Dash said.

Did the ancient Egyptians actually use it?

The recent experiment shows that the fall equinox could have been used to align the three pyramids, Dash said. However, whether the ancient Egyptians used this technique is unknown. Experiments conducted over the past few decades suggest that several methods that make use of the sun or stars could also have been used to align the pyramids, Dash said.

The ancient Egyptians left no surviving records that say which methods they used.

"The Egyptians, unfortunately, left us few clues. No engineering documents or architectural plans have been found that give technical explanations demonstrating how the ancient Egyptians aligned any of their temples or pyramids," Dash wrote in the article. In fact, it's possible that multiple methods were used to align the pyramids, Dash told Live Science.

The fall equinox method does have an advantage: It's relatively simple to use. Other methods require more steps and are generally more complicated, he said. "It is hard to imagine a method that could be simpler, either conceptually or in practice," than the fall equinox method, Dash wrote.

Dash is the founder of the Glen Dash Foundation for Archaeological Research. He conducts work on the Giza Plateau with Ancient Egypt Research Associates and has conducted radar work in the Valley of the Kings.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.